Psychology Classics On Amazon

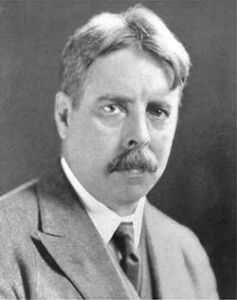

Edward Thorndike

Edward Thorndike was born on the 31st August 1874. An influential figure in the early days of modern psychology, Thorndike obtained his M.A. degree under the supervision of William James at Harvard before transferring to Columbia to study animal intelligence with James McKeen Cattell; during which time he earned his Ph.D. in the subject, a landmark moment in the scientific study of animal behavior.

It is, however, for his pioneering contribution within the field of educational psychology that Thorndike is best remembered. In the course of a long and prodigious academic career Thorndike published over 500 papers on topics including, laws of learning, educational statistics, achievement tests and scales, transfer of training, group intelligence and adult learning.

Edward Thorndike died on the 9th August 1949.

The following tribute was written by Arthur Gates.

Edward Thorndike died on August 9, 1949, three weeks before his seventy-fifth birthday and a half century, almost to the day, after his acceptance of a post in Teachers College, Columbia University, which he served continuously until his retirement at sixty-five, and in which he has held since then the title of Emeritus Professor.

Thorndike received the B.A. degrees from Wesleyan University (Connecticut), 1895, and from Harvard, 1896. Working under William James, he earned the M.A. degree at Harvard in 1897 and then transferred to Columbia to study with Cattell under whom he took the Ph.D. degree in 1898, offering as his dissertation Animal Intelligence, which has been regarded by many psychologists as marking the beginning of the scientific study of animal behavior. During the following year he taught psychology at Western Reserve University in Cleveland. On taking the post at Teachers College, Columbia University, in 1899 he launched his career in educational psychology.

At the time of Thorndike's death the staff in educational psychology at Teachers College were rounding out certain reports of his activities, especially those carried on since his retirement, to present to him on his seventy-fifth birthday. Among these papers is a bibliography of his publications to date. It contains 508 titles, almost exactly ten per year for the period of fifty-one years. The range of fields in which he worked is as unusual as the volume of his reports. He contributed comprehensive books or research reports or theoretical discussions, usually all of these, in almost every major area of psychology and education, and in many special fields such as lexicography and city planning.

In many of these areas Thorndike's contributions have become major considerations of scholars throughout the world. The following seem now to be regarded as of outstanding importance: his methods of studying animal learning; his "laws of learning"; his attacks on formal discipline and his theory of transfer of training; his introduction of statistical methods to education and educational psychology; his development of achievement tests and scales; his detailed methods and materials for the teaching of arithmetic, algebra, reading, spelling, and other school subjects; his work on group intelligence tests, especially those for adults; his theory of intelligence; his analysis of work and play; his concept of the "original nature of man"; his investigations of the nature-nurture problem; his defense of the idea that mental "qualitative" differences can be explained as "quantitative"; his studies of vocabulary; his new pattern for the dictionary; his investigations of adult learning; and his theories of human nature in relation to society.

Thorndike's prodigiously vigorous work was guided by three major purposes: to demonstrate the law-abiding character of all human behavior, especially mental behavior; to show the unrivaled fruitfulness of applying the methods of science to the problems of the individual and society; and to launch within psychology the policy of employing patterns of quantitative research as exacting as those employed in the physical sciences. In the early years of his career, psychologists as well as educators, philosophers and religious leaders were shocked by his insistence that "anything that exists, exists in some amount and can be measured" and in the later years some representatives of all these groups misunderstood his conviction that quantitative increments can account for apparent or real qualitative differences. A basal principle in Thorndike's code as scientist was, for example, that the difference between a genius and an imbecile, and between insightful learning and trial and error learning, can be explained, for scientific purposes, more helpfully as quantitative than as qualitative differences. Accordingly he opposed all his life the tendency within the social sciences to accept such popular concepts as "reason," "insight," "intelligence," and other "mystic potencies" as sound or useful explanations of mental activity.

For today and tomorrow's students who wish to explore Thorndike's psychology with some thoroughness, the bibliography of his published works up to April 1940, published in the Teachers College Record of May 1940, will be brought up to date in the October 1949 issue of the same journal. Only a few days before his death Thorndike finished correcting page proofs of a moderately sized volume, Selected Writings from a Connectionist's Psychology, which consists of his own selections from his writings, a book which provides a convenient brief introduction to the character and range of his work.

Thorndike was a member of a large number of scientific and other scholarly societies, including the National Research Council, and served as President of the American Psychological Association, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the New York Academy of Science, the Association of Adult Education, and others. He received honorary degrees from seven universities: Wesleyan, Columbia, Chicago, Athens (Greece), Harvard, Iowa, and Edinburgh. He received the Butler Medal in gold from Columbia in 1925 for "exceptionally distinguished contributions" to the social sciences. He was a member of the Century Club.

Thorndike received all his schooling except for the final year at Columbia in New England where his father was a Methodist minister. At the age of twenty-six he married Elizabeth Moulton, of Boston. His brother, Ashley, deceased, was Head of the Columbia University Department of English; his brother, Lynn, is a member of the Columbia Department of History, and his sister recently retired from teaching in a high school. His living descendants are a daughter, Mrs. Freeman Cope, who at one time taught mathematics at Vassar College; his sons, Edward, Professor of Physics, Queens College; Robert, Professor of Education, Department of Educational Psychology, Teachers College, and Alan, a Harvard Ph.D. in physics, now engaged in research in a government agency, and thirteen grandchildren.

A few words should be said about Thorndike as a man, especially for those whose contacts with him were casual. Physically he was often described as a rugged "bear of a man." He was the friendliest of persons, generous and kind, even if quick to rebuke a wrong. Although his theories were the center of controversies all his life, he took criticism, even stupid abuse, with attentive good will, and his own criticisms were directed at issues and not at people. His buoyant good humor and sparkling wit made him a delightful companion, teacher, and public speaker. So great was his enjoyment of his work that he spent relatively little time, even after his retirement from Columbia, in conventional play. He often chuckled that "the college pays me for doing the very things I like most of all to do." As a young man, however, he relished his canny game of tennis, and later on an occasional game of bridge or a detective story, and those of us who have lived near him prize Thorndike, the genial country gentleman, as much as Thorndike, the psychologist.

Recent Articles

-

Cute Aggression Explained: Why We Want to Squeeze Adorable Things

Apr 09, 25 01:24 PM

Overwhelmed by cuteness? Discover the science behind cute aggression, the brain's quirky way of handling too much joy. You’ll never see cute the same again. -

Psychology Book Marketing Services

Apr 08, 25 11:44 AM

Want a massive audience of psychology lovers to know about your book? I can help! -

Unparalleled Psychology Advertising Opportunities

Apr 08, 25 11:43 AM

Psychology Advertising: Connect With Hundreds Of Thousands Psychology Enthusiasts

Please help support this website by visiting the All About Psychology Amazon Store to check out an awesome collection of psychology books, gifts and T-shirts.

Go From Edward Thorndike Back To The Home Page