Psychology Classics On Amazon

Cute Aggression Explained: Why We

Want to Squeeze Adorable Things

Introduction

Cute aggression is a recently defined phenomenon in which encountering an extremely cute stimulus (like a baby or puppy) elicits sudden aggressive urges – such as wanting to squeeze, bite, or pinch – without any actual intent to harm. This paradoxical response has puzzled both scientists and laypeople. After all, the physical traits we deem “cute” – big eyes, chubby cheeks, tiny bodies – signal vulnerability and tend to evoke caregiving and tenderness, not violence. Yet many people “can’t stand” how cute something is and exclaim “It’s so cute I want to crush it!” or “I want to eat you up!” while gritting their teeth or clenching fists. Such expressions of aggression toward cuteness are dimorphous, meaning they are outward displays that don’t match the positive emotion felt internally. Importantly, the aggressive urges in cute aggression are playful and non-serious – the person has no desire to actually hurt the adorable target.

Interest in cute aggression has grown in both affective science and popular culture. Psychologists view it as a window into how we express and regulate strong emotions, blurring the lines between positive and negative expression. At the same time, viral internet memes (for example, “It’s so fluffy I’m gonna die!” from the animated film Despicable Me) and social media posts about “squeezing kittens” have made cute aggression a buzzworthy pop-psychology topic. Understanding why the brain’s response to overwhelming cuteness manifests in such a contradictory way can shed light on emotional regulation mechanisms and even evolutionary instincts.

This article provides an in-depth exploration of cute aggression. We will begin by defining the concept and its theoretical foundations, including the idea of dimorphous expressions, evolutionary theories, and communication functions. Next, we delve into the neuropsychological mechanisms underlying cute aggression, examining which brain regions, neurochemicals, and physiological responses are involved. We then consider evolutionary and developmental perspectives – why might this odd response have adaptive value, and how is it observed across cultures or in different life stages? Real-world examples and implications will be discussed, from everyday experiences (squeezing a plush toy) to how marketers capitalize on cuteness. We also address the clinical and psychological relevance of cute aggression, such as its role in emotion regulation and the fact that it is not indicative of pathology. Finally, we summarize key findings and suggest avenues for future research on this fascinating emotional phenomenon.

Theoretical Foundations

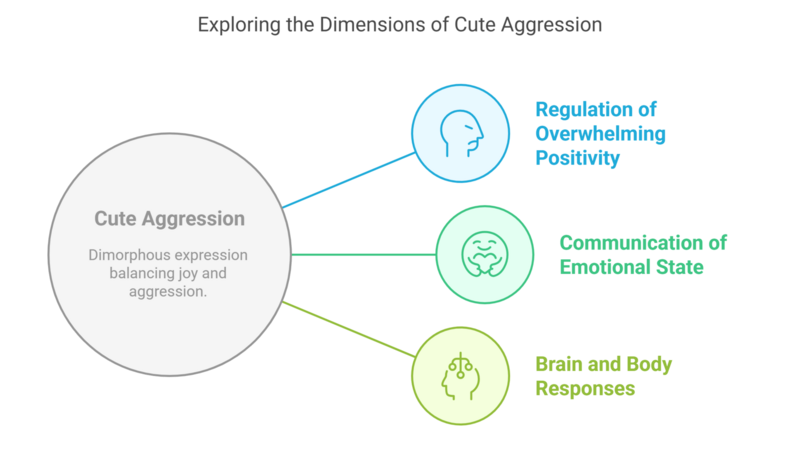

The term “cute aggression” was first introduced in scientific literature by Oriana Aragón and colleagues in 2015. In that landmark study, Aragón et al. operationalized cute aggression as “the urge some people get to squeeze, crush, or bite cute things, albeit without desire to cause harm.” Participants viewing images of infantile babies and baby animals reported occasional aggressive impulses (like wanting to pinch or squeeze) precisely when they felt overwhelmed by positive feelings of adorableness. This counterintuitive combination of tenderness and aggression was identified as a type of dimorphous expression – a term describing instances when a strong emotion triggers its opposite expression. In other words, a single intense emotional experience (in this case, joy or affection elicited by cuteness) can produce two outward expressions: one that matches the positive emotion (e.g. smiling or cooing) and one that appears negative or incongruous (e.g. a snarling expression or aggressive exclamation). Dimorphous expressions aren’t unique to cuteness; other examples include happy tears (crying when joyous) or nervous laughter (laughing when anxious). What they have in common is a kind of emotional overflow—when feelings hit a threshold of intensity, the expression system “flips” into an opposite mode, perhaps as a way to restore balance or communicate complexity.

Aragón’s work established cute aggression as a real and measurable phenomenon and spurred questions about its function. Initially, one hypothesis was rooted in emotional regulation: perhaps these aggressive urges act as a homeostatic mechanism, dampening intense positive affect so that one isn’t incapacitated by overwhelming cuteness. Feeling too much positive emotion (so much that “it hurts”) could potentially be maladaptive – for example, an overstimulated caregiver might freeze up or fail to care effectively for an infant. In this view, expressing a bit of mock aggression might help the person discharge excess arousal and regain composure. Indeed, Aragón’s team found evidence supporting this: individuals who exhibited dimorphous expressions (like cute aggression or happy crying) reported that these expressions helped them recover from strong emotions, suggesting a regulatory function.

Another framework for understanding cute aggression comes from behavioral ecology and communication theories of emotion expression. Rather than being just an internal pressure valve, the strange blend of aggression with affection may serve a social signaling role. According to Fridlund’s behavioral ecology view, facial expressions and emotional displays evolved to communicate our intentions and motivate social partners, not simply to reflect our feelings. In the context of cute aggression, what might an aggressive-sounding gush of emotion communicate? Aragón and others have suggested that it sends a “powerful signal” to others about how strongly we feel and how we intend to behave. For instance, telling a parent “Your baby is so cute I could just eat her up!” or playfully pinching a baby’s cheeks in front of the baby’s mother actually conveys love and approach intent, not danger. The aggressive wording or gesture may be a way to emphasize just how adorable the baby is – essentially broadcasting “I’m so enchanted that I’m losing control!” – which paradoxically might reassure others of the intensity of care. In support of this, researchers note that a normal smile or simple “aww” might not fully capture the urgency or depth of feeling, whereas a dimorphous expression like mock-aggression “adds information” about our motivational state. The exaggerated, seemingly out-of-place act (growling happily, etc.) can prompt those around to understand the person is overwhelmingly pleased and intends to engage with the cute object (e.g. wanting to hold or protect it). In short, what looks like aggression on the surface is actually a social cue of strong affection and a desire to nurture.

Cross-cultural observations support both the universality of cute aggression and the idea that expression norms can shape its display. While English lacks a single word for this urge, other languages do. For example, Filipino has the term “gigil,” which specifically refers to the gritting of teeth and irresistible urge to pinch or squeeze something unbearably cute. Many people around the world report experiencing the same urge when confronted with extreme cuteness. In studies conducted in the United States and South Korea, Aragon found that both American and Korean participants showed dimorphous expressions (including cute aggression) in response to cute images, and this was true for men as well as women. Cultural norms, however, influenced how the emotion was channeled: for example, Americans were somewhat more likely to use aggressive body language (clenched fists, gritted teeth) to express positive feelings, whereas Koreans more often showed tears of joy in positive situations. Despite different stylistic expressions, the core phenomenon – mixing positive emotion with an opposite-valence expression – appears to be a common human experience.

In summary, theoretical perspectives on cute aggression highlight it as a dimorphous emotional expression that might function to regulate overwhelming positivity and/or to communicate one’s emotional state to others. The discovery of cute aggression expanded our understanding that joy can paradoxically produce aggressive behaviors, not out of malice but as part of the complex tapestry of human emotional expression. With this foundation, we can explore what happens in the brain and body during cute aggression and why such a response may have developed.

Neuropsychological Mechanisms

From a neuropsychological standpoint, cute aggression involves a blend of neural processes related to reward, emotion, and social bonding – but notably not the same patterns as actual anger or violence. Early research on cuteness (even before “cute aggression” was coined) showed that baby-like features activate the brain’s reward circuitry. In a 2009 functional MRI study, Glocker et al. found that women viewing infant faces with exaggerated Kindchenschema (baby schema) features had increased activity in the nucleus accumbens, a key reward center in the brain. The nucleus accumbens (part of the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system) mediates feelings of pleasure and motivation – it’s the same region that lights up for delicious food, addictive drugs, or other rewarding stimuli. In response to cute baby faces, greater nucleus accumbens activation suggests that our brains experience cuteness as a highly rewarding, positive stimulus, which in turn can trigger strong approach impulses (we feel a desire to move closer, hold, or care for the cute being). Along with the nucleus accumbens, other brain areas such as the amygdala have been implicated in processing cute stimuli. The amygdala, often associated with emotion and salience detection, is engaged by baby schema as well; seeing something extremely cute stimulates brain regions like the nucleus accumbens and amygdala, which are linked to emotional processing and pleasurable feelings. This neural activity corresponds to the subjective “aww” response – the burst of joy and affection we feel when we see a cute infant or pet – and lays the groundwork for the puzzling aggressive urge that follows.

Notably, the brain activation pattern underlying cute aggression appears to overlap with reward and caregiving systems, not with areas typically involved in overt aggression. One recent study using electrophysiology measured adults’ brain responses while viewing images of “high-cute” vs “low-cute” babies and animals (e.g., puppies vs. adult dogs). The researchers, Stavropoulos and Alba (2018), identified neural signatures corresponding to participants’ self-reported cute aggression. They found that when participants looked at extremely cute images, their brains showed amplified responses in components associated with emotional salience (the N200 wave) and reward processing (the “reward positivity” or RewP). In fact, individuals who reported stronger urges of cute aggression exhibited larger reward-related brain responses to cute images. This suggests that cute aggression is fueled by a sort of neural overflow of positivity – the brain’s reward centers (like nucleus accumbens and ventral striatum) are highly active, perhaps pumping out dopamine in response to the cute stimulus, and the person is emotionally “overloaded”. The N200 component, which indexes detection of emotionally significant stimuli, was larger for cuter images, indicating the brain flagged those adorable babies and animals as particularly salient or attention-grabbing. At the same time, the heightened reward signal (RewP) for cute images correlated with how much cute aggression the person felt. Together, these findings paint a picture of a brain in overdrive: it intensely values the cute stimulus (reward circuit firing), and it is strongly emotionally engaged (salience and affect circuits firing). There is no evidence, however, that brain areas for genuine anger or intent to harm (such as the threat-responsive circuits of the amygdala-hypothalamus or regions like the periaqueductal gray involved in rage) are specifically activated in cute aggression. In fact, one analysis noted that “areas of the brain associated with both reward and emotion, but not aggression,” are responsible for cute aggression. The term “aggression” in this phenomenon is thus a misnomer – neurologically, it’s not about anger at all, but about intense positive reinforcement.

To better illustrate the neural profile of cute aggression, Table 1 summarizes key brain regions and neurochemical factors involved when we encounter something adorably cute and experience this odd aggressive urge.

| Neural Component / Region | Role in Cute Aggression Response |

|---|---|

| Nucleus Accumbens (NAcc) – brain reward center, part of ventral striatum | Highly activated by cute stimuli (e.g., baby faces), reflecting a surge of reward processing. This corresponds to dopamine release and feelings of pleasure. The stronger the activation, the more one might feel an urge to approach or hold the cute target (a precursor to the playful “squeeze” urge). |

| Amygdala – emotion and salience detector in the limbic system | Involved in tagging the cute stimulus as emotionally arousing or significant. Baby schema features stimulate the amygdala along with NAcc, contributing to that feeling of being overwhelmed by cuteness. (Not associated with fear/threat in this context, but rather with positive arousal.) |

| Frontal Cortex – regulatory and evaluative regions (e.g., orbitofrontal cortex) | Likely engages in appraising the situation: “This is so cute!” and simultaneously restraining actual action (“Don’t literally squeeze too hard.”). The orbitofrontal cortex, which evaluates reward value, may register the cute stimulus as highly valuable. Some fMRI evidence shows frontal areas respond to infant cuteness and help modulate caregiving impulses. |

| Hypothalamus – hormonal command center, linked to aggression and parenting behaviors | While not specifically measured in current cute aggression studies, the hypothalamus is a candidate in coordinating the body’s response. It governs oxytocin release and maternal behaviors, and in other contexts, can trigger aggression responses. In cute aggression, the hypothalamus might integrate the high arousal with hormonal signals (like oxytocin) to balance caretaking urges and aggressive feelings. |

| N200 (ERP component) – early neural marker of emotional significance (peaks ~200ms) | Larger amplitude N200 waves occur when viewing very cute images compared to less cute ones. This indicates the brain rapidly detects cuteness as an emotionally important stimulus. People prone to dimorphous expressions (e.g., happy criers) also show bigger N200s for cute things, suggesting a general sensitivity to intense emotions. |

| RewP (Reward Positivity, ERP) – neural response (~300ms) to reward outcomes or cues | Enhanced when viewing cute babies/animals, especially in individuals reporting strong cute aggression. A higher RewP signifies that the brain is treating cuteness akin to a rewarding event. This heightened reward signal has been linked through mediation analyses to feeling “overwhelmed” and then expressing cute aggression, supporting the idea that reward activation feeds into the aggressive urge. |

| Dopamine – neurotransmitter central to reward and motivation | Likely released in abundance upon seeing something extremely cute (due to NAcc activation). Dopamine contributes to the “high” or excitement one feels. It may also underlie the energetic motor tension (grinning, clenching) that accompanies the urge. In essence, a cute stimulus gives the brain a mini dopamine rush (a rewarding jolt) that might overshoot equilibrium, prompting regulatory responses. |

| Oxytocin – hormone associated with bonding, caregiving, and affection | Elevated during interactions with infants and cute pets, oxytocin intensifies feelings of love and attachment. It’s possible that seeing a cute baby or puppy triggers oxytocin release, deepening the caregiving impulse. Research shows that administering oxytocin amplifies neural responses to baby faces in mothers. Thus, oxytocin might make the cute stimulus even more rewarding, potentially increasing the need for a balancing mechanism like cute aggression. |

As shown in Table 1, the neuropsychology of cute aggression is largely about too much of a good thing: the brain’s positive reinforcement systems go into overdrive. The combination of dopamine-fueled reward and intense emotional arousal can produce a kind of euphoric agitation. People often describe a tension – “It’s so cute I’m going to explode!” – which aligns with this neural picture. To an outside observer, the person’s grinning-yet-grimacing face or squeals about “squeezing” something cute might look odd. But internally, it reflects the brain trying to restore emotional equilibrium. By expressing a faux aggressive impulse, one might activate neural pathways that counteract the giddy excitement (perhaps engaging some inhibitory control or stress-response circuits just enough to calm down). In essence, the mild aggressive display could be the brain’s way of dialing back the extreme positive arousal, preventing us from becoming so overloaded with joy that we neglect practical action (like actually caring for the baby).

In summary, neuroscientific studies indicate that cute aggression is driven by heightened reward activity and emotional salience, not true anger. The urge to squeeze a cute creature stems from our brain receiving a potent dose of “aww-induced” pleasure (dopamine, oxytocin, etc.) combined with a need to regulate that surge. It’s a striking example of how closely pleasure and pain, or joy and aggression, can intersect in the brain when emotions run high. Next, we consider why evolution might have shaped such a response and how it manifests across development.

Evolutionary and Developmental Perspectives

At first glance, cute aggression seems counterproductive – why would evolution favor an urge that superficially looks like hostility toward one’s own offspring or other cute creatures? Researchers propose that this peculiar response may actually confer adaptive benefits by ensuring we can effectively care for vulnerable young without becoming overwhelmed by positive emotion. This ties into the classic concept of the Kindchenschema, or baby schema, identified by ethologist Konrad Lorenz (1943). Baby schema refers to a set of infantile features (a large round head, big eyes, button nose, clumsy movements, etc.) that trigger innate caregiving motivations in adults. From an evolutionary standpoint, when early humans (or other animals) found their infants irresistibly cute, they would be motivated to protect and nurture them, thus increasing the offspring’s chances of survival. Indeed, cuteness is thought to be a trigger for caregiving behavior across species – we are hardwired to respond to “adorable” features with approach, tenderness, and attentiveness.

However, there is a potential downside to this ultra-effective cuteness trigger: too much parental gooey-eyed awe could be paralyzing or distracting. If a caregiver is so enchanted by an infant’s cuteness that they simply sit stupefied, or if the positive emotion is so strong it becomes stressful, the caregiver might fail to perform necessary tasks (feeding, protecting from threats, etc.). Therefore, scientists theorize that cute aggression evolved as a balancing mechanism or a “release valve” for our nurturing system. As one professor explained, “if you’re overcome by the cuteness, then you might not be able to properly take care of it, so the brain needs to bring us back a bit – that’s apparently where cute aggression comes in.” In this view, when the “cuteness overload” alarm goes off, the brief flash of aggression helps us re-ground ourselves. The jolt of an aggressive impulse counteracts the flood of caretaking emotion just enough to keep us functional and attentive. This idea aligns with the earlier discussion of emotional homeostasis: expressing a little bit of aggressive tension may keep our positive emotions at an optimal level rather than a debilitating extreme. It’s analogous to how some people tear up when extremely happy – the tears might prevent a person from spiraling into a euphoric daze by injecting a sobering element. For our ancestors, experiencing cute aggression could have meant “I love my baby so much I could squeeze her! (deep breath) Alright, focus – time to actually take care of her.” In short, cute aggression may be adaptive by ensuring that intense affection does not sidetrack the practical caregiving tasks at hand.

Another evolutionary angle is that cute aggression could serve as a gentle reminder of the fragility of cute things, thereby enhancing protective instincts. When someone says “I want to eat you up!” to a baby, the absurdity of the statement underscores that of course they must not harm the baby. Some theorists suggest that having a split-second aggressive fantasy makes the brain immediately contrast it with reality, reinforcing the knowledge that the infant is delicate. In other words, the notion “I could just squeeze you!” is followed by an implicit “...but I won’t, because you’re tiny and I need to be gentle.” This could make the caretaker even more careful thereafter. There’s some evidence consistent with this: one study found that people actually became more careful and precise in their motor tasks after viewing very cute images, presumably because the cuteness triggered a protective, detail-oriented mode appropriate for handling something fragile. Thus, cute aggression might indirectly promote gentleness. The aggressive thought is fleeting and never enacted, but it perhaps helps calibrate our behavior to be extra cautious with the cute object.

Developmentally, cute aggression appears to be a widespread human experience, though individuals vary in degree. It is not limited to a particular age or gender. Even children can feel it – for example, Aragón recounted a story of an 8-year-old girl who felt such strong cute aggression toward her newborn baby sister that she unknowingly cracked her own tooth from clenching her jaw. (The child was overwhelmed with love, not intending harm.) This suggests that the phenomenon is linked to fundamental emotional processes that are present early in life. It might also indicate that children, who have less refined emotion-regulation skills, can experience the “overflow” of cuteness more intensely, leading to physical reactions like jaw clenching. On the other hand, as people grow up and learn social norms, they might channel their cute aggression into more subtle expressions (like saying something silly) rather than actual squeezing.

Regarding individual differences, research finds that not everyone experiences cute aggression, and that’s okay – it’s just one end of the spectrum of responses to cuteness. Some people simply feel pure melted hearts with no urge to squish; others almost always get that wild “I’m gonna burst!” feeling when confronted with adorable babies or pets. Personality or temperament could play a role: those who are highly expressive or who tend to experience emotions intensely may be more prone to dimorphous expressions. Interestingly, studies have noted that people who exhibit one type of dimorphous expression often exhibit others. So, the wedding crier is also more likely to be the puppy squeezer and the nervous giggler. Meanwhile, someone who never cries for joy might also report never understanding cute aggression. These are normal variations in emotional expression styles.

Another factor that might influence cute aggression is parental status and experience. One might expect that parents, especially new mothers and fathers, could have different responses to infant cuteness compared to non-parents. A new parent’s daily exposure to their own (highly cute) baby could either habituate them somewhat – making them less likely to feel overwhelmed – or conversely heighten their sensitivity due to hormonal changes and bonding. While formal studies are sparse, researchers have speculated about this. In one experiment, a participant mused that perhaps people who have children experience more cute aggression toward babies than those who don’t, given parents’ strong attachment and constant exposure. There is also a biological basis to consider: postpartum women have elevated oxytocin and other neurochemicals that promote bonding, which might amplify emotional responses to infant cues. (In animal studies, for instance, mother rats will show both intense nurturing and heightened defensive aggression to protect pups, mediated by hypothalamic circuits – a reminder that caregiving and aggression can be closely linked in parental brains.) Future research is needed to clarify if parents differ in cute aggression. Anecdotally, many parents do report playful aggressive urges like nibbling their baby’s toes or play-biting – behaviors often accompanied by affectionate laughter and understood as love displays. It’s likely that whether one is a parent or not, cuteness reliably activates the caregiving system in the brain; cute aggression would just be one quirky output of that activation.

Finally, it’s worth noting the cross-cultural consistency of cuteness perception and response. The Kindchenschema features that humans find cute tend to be universal: across cultures, people gravitate toward big-eyed, round-faced babies and even apply the term “cute” to animals or objects with similar traits. Evolution likely hard-wired these preferences because human infants (regardless of culture) share those baby characteristics and require adult care. As mentioned, cultures have their own terms or expressions for cute aggression (such as gigil in the Philippines). Cross-cultural studies by Aragón and others in the U.S. and East Asia show that both the perception of cuteness and the occurrence of dimorphous expressions are present in different societies, though shaped by social norms. For example, while an American might playfully growl “I just wanna bite that baby!”, someone in a different culture might simply express being moved to tears by the baby’s beauty – different surface expression, but potentially the same underlying overwhelm of positive feeling. The core evolutionary impulse – to care for the cute and not harm it – remains constant.

In summary, evolutionary theory suggests cute aggression is adaptive, functioning to prevent emotional overload and ensure effective caregiving of irresistibly cute, vulnerable young. Developmentally, it is a common human experience that can appear early in life and varies among individuals without indicating any abnormality. The next section will connect these scientific insights to everyday life, illustrating how cute aggression plays out in real-world scenarios and how it even finds its way into social media trends and product designs.

Real-World Examples and Implications

Almost everyone can recall a time they or someone they know squealed about a cute baby or pet and said something absurd like, “It’s so cute I could just squeeze it to death!” Such expressions are typically accompanied by a happy smile, perhaps wincing or baring teeth, and a high-pitched tone of voice. In daily life, cute aggression often strikes in mundane moments – one might be scrolling through social media, encounter an impossibly cute puppy video, and find themselves clutching their phone a little tighter or exclaiming out loud. Social media and meme culture have embraced this concept wholeheartedly. For instance, the meme above of Agnes from Despicable Me hugging a fluffy unicorn and yelling “It’s so fluffy I’m gonna die!” became an iconic representation of the overwhelming feeling of encountering cuteness. People caption photos of kittens or babies with this phrase to humorously convey that they are experiencing an overload of adorableness. Memes with phrases like “SCREAMING BECAUSE CUTE” or “I just wanna squeeze you!” abound, indicating how relatable the sentiment is. Importantly, everyone understands it’s tongue-in-cheek – no one interprets these comments as actual threats. In fact, such exaggerated statements have become a socially accepted way to express great affection. Telling a friend “Your baby is so cute I could eat her up!” is often received as a quirky compliment, not a cause for alarm, because we intuitively grasp the concept of playful aggression in the context of cuteness.

These real-world expressions of cute aggression serve a few social functions. For one, they create a shared understanding of intense appreciation. If two people see a photo of a panda cub and one says, “Gah! I’m gonna die, it’s too cute,” the other likely nods vigorously – exactly, me too! It’s a way of bonding over positive emotion. Additionally, voicing cute aggression can sometimes defuse what might otherwise be an overly sentimental moment by injecting a bit of humor or edge. For example, rather than just cooing continuously at a baby (which might feel socially excessive), a person might joke about wanting to “steal them” or “squish them”, thus conveying their adoration in a lighthearted, less saccharine way.

In marketing and design, understanding cute aggression and the power of cuteness has practical implications. Advertisers have long exploited the allure of cute animals and babies – think of the many commercials featuring puppies, kittens, or the iconic Gerber baby – to capture consumers’ attention and goodwill. The Yale researchers who coined cute aggression also noted how products with “cute” aesthetics can provoke strong responses. For instance, cars with round headlights and a “face-like” front (like the Volkswagen Beetle) or gadgets with toy-like proportions trigger that same aww reaction. While encountering a cute product might not make us want to bite it, it does engage the emotional reward system, potentially making the experience of that product more enjoyable or memorable. Some marketing experts have even discussed cute aggression in advertising contexts, suggesting that part of the reason cute animals in ads are effective is that they evoke such a strong, automatic emotional response that viewers are drawn in (and perhaps will pay more attention or feel more connected to the message).

Designers of toys and collectibles also play into this effect. Consider the popularity of extremely cute, big-eyed plush toys (like the “Beanie Boos” with oversized sparkly eyes, or Japanese mascots like Hello Kitty). People often react to these items with an “It’s so cute I can’t!” and give them a squeeze – which is exactly the point. The softness of a plush toy provides a safe outlet for any squeezing urge. In fact, one could argue that giving a child a soft teddy bear to hug when they see something cute might channel any aggressive energy harmlessly. Similarly, internet trends like “squishy” stress toys (foam toys shaped like cute animals or food with faces) allow folks to literally squeeze something cute because it’s cute – a direct manifestation of cute aggression that doubles as stress relief.

Researchers measure cute aggression in various creative ways. Besides questionnaires asking people to rate their agreement with statements like “I can’t stand how cute this is – I want to squeeze it,” scientists have used behavioral proxies. A clever example is the bubble wrap experiment: After showing participants slideshows of images (cute baby animals, funny scenes, or neutral objects), the experimenters provided sheets of bubble wrap and told participants they could pop as many bubbles as they wanted while viewing the images. Remarkably, people who watched the cute slideshow popped significantly more bubbles than those who watched the neutral or funny slideshows. In other words, the cuter the content, the more destructive popping behavior was observed – a playful lab simulation of aggressive squeezing. This helped confirm that the urge wasn’t just verbally reported; it had an observable component (increased motor activity when experiencing high cuteness). Other methods involve facial electromyography (EMG), which can detect subtle muscle movements. Although primarily used to measure genuine negative or positive expressions, EMG could capture the simultaneous activation of smiling muscles and muscles involved in clenching or frowning when someone experiences cute aggression. For example, one might see activation of the zygomatic major (smile muscle) alongside the masseter (jaw clench) or corrugator supercilii (frown muscle), reflecting the mixed emotional display on the face.

In casual settings, people often self-regulate their cute aggressive impulses with little actions: making a mock snarling face, lightly pinching a baby’s cheek or a pet’s ear (in a gentle way that often even pleases the baby or pet), or chanting playful threats (“I’m gonna get you!” while hugging a child). These behaviors usually make the recipient laugh or smile; there’s a mutual understanding of affection. On the flip side, it’s important socially that we gauge context: Not everyone is familiar with the term cute aggression, so an overly vehement expression could be misinterpreted by someone unacquainted with the concept. Imagine a stranger approaching a baby in a stroller and exclaiming “I want to bite those little toes!” – the parent might be taken aback if they’ve never heard of this and could respond protectively. Thus, people tend to reserve these comments for close others or accompany them with clarifying cues (laughing, obviously gentle tone) to ensure no one is alarmed.

In terms of broader societal implications, recognizing the prevalence of cute aggression can lead to a better understanding that intense positive emotions can have strange manifestations. This insight has filtered into popular psychology coverage, helping people not to feel “weird” or guilty about their odd urges. Many individuals have been relieved to learn that there’s a name and an explanation for the “I want to squeeze it!” feeling – that they aren’t secretly abusive or crazy, but rather experiencing a normal human quirk. Media outlets from NPR to The Conversation have published explainer pieces on cute aggression, normalizing it and describing it as a curious but ultimately harmless aspect of emotional life. As one science writer put it, it’s “tantalizing” because it shows how emotion and expression can mismatch, but it’s also reassuring to know that having these urges is not a sign of actual aggression or danger.

Furthermore, understanding cute aggression can inform caregivers and educators. For example, if an older sibling is overly rough with a new baby (out of excitement, not anger), parents can recognize it might be an expression of cute aggression and gently teach the child about being careful, rather than punishing them for “meanness” they didn’t intend. Pet owners similarly might note that a child squeezing a puppy is doing so out of love, and can channel that enthusiasm into gentle petting or supervised play instead.

In summary, cute aggression permeates everyday experiences from our personal interactions (the urge to pinch a loved one’s adorable cheeks) to cultural products (memes, toys, advertisements). It underscores the complexity of human emotion: even our joy has a shadow in play. By measuring and acknowledging it, we can better harness the positive aspects – delight, bonding, humor – while managing the impulses in safe, constructive ways.

Clinical and Psychological Relevance

Psychologically, cute aggression highlights how our minds strive for emotional equilibrium. It can be viewed as one of the brain’s many emotion regulation strategies – largely unconscious in this case – to keep intense affect in check. Importantly, experiencing cute aggression is considered non-pathological. In fact, it might be a sign of a well-tuned emotion regulatory system that can automatically curb extremes of feeling. People sometimes worry that having thoughts like “I want to squeeze this puppy till it pops” means there’s something “wrong” with them, but research emphasizes that these urges are normal and do not translate into actual violent behavior. Part of disseminating the concept of dimorphous expressions (like cute aggression) is educating the public that feeling an urge is very different from acting on it, and in this case the urge itself is a quirky byproduct of too much love, not hate.

That said, could there be individual differences that make cute aggression more pronounced in some or tied to other emotional traits? Studies suggest that individuals who frequently exhibit dimorphous expressions (whether it’s crying when happy or play-acting aggression when affectionate) may have higher emotional reactivity in general. They might also score higher on traits like empathy or anxiety – essentially, feeling emotions strongly and perhaps sometimes becoming overwhelmed by them. Cute aggression could then be their mind’s way of venting that excess. On the other hand, someone more phlegmatic or reserved might enjoy cute things without ever hitting that overload point, and thus not experience the phenomenon. Neither end is inherently better or worse; as one psychologist noted, “There are always individual differences between us… we all experience and process things differently. Whatever your response, it simply sheds light on the fascinating interplay between our brains, our emotions, and our behavior.”

From a clinical perspective, understanding cute aggression could intersect with research on emotion regulation and mental health. If cute aggression indeed reflects a healthy balancing mechanism, one could ask: do people with certain disorders experience it differently? For example, consider individuals with depression, who often have blunted ability to feel positive emotions (anhedonia). Would a depressed person less frequently report cute aggression because they rarely get that excited by cuteness? Or might they actually find it helpful if they do – perhaps the little jolt of aggression counteracts a tendency to sink when feeling overwhelmed? Conversely, individuals with anxiety might feel particularly overwhelmed by strong emotions and thus could have noticeable dimorphous reactions as a coping method. Another angle is conduct disorder or psychopathy – those who lack typical empathy or caregiving impulses. A 2018 study proposed investigating whether people with disrupted reward/emotion systems (like youth with conduct disorder who have callous-unemotional traits) would show the normal patterns of cute aggression or not. If someone doesn’t find babies cute or doesn’t get that warm fuzzy surge, they likely won’t need to down-regulate it, and thus might not relate to cute aggression. Studying such populations could deepen our understanding of how tightly linked positive emotions and their regulatory “brakes” are.

It’s also interesting to consider postpartum mothers from a clinical angle. Postpartum depression can impair a mother’s bonding with her infant. Would a mother with postpartum depression exhibit less cute aggression (because she might not get the usual reward high from her baby’s cuteness)? If so, could the absence of such responses be a subtle indicator of bonding difficulties? These are speculative questions, but they illustrate how even a seemingly whimsical topic like cute aggression can have relevance to attachment and affective disorders. On the flip side, mothers who are very bonded might report strong urges to nibble their baby (think of the common behavior of parents playfully nibbling tiny baby fingers or feet). That is actually a positive sign of affection. Clinicians generally would not pathologize that at all; if anything, it indicates the parent is deeply engaged. Only if someone were to actually hurt a child or pet would alarm bells ring, and in those cases it wouldn’t be classified as “cute aggression” but rather as a failure of restraint or a sign of other issues.

Emotion researchers have been keen to stress that cute aggression is not a form of genuine aggression or anger. Biologically, it doesn’t recruit the autonomic and hormonal profiles of rage – for example, one’s heart rate and blood pressure might spike from excitement, but not in the pattern typical of anger (which involves distinct adrenaline surges and often trigger feelings of frustration or threat). People experiencing cute aggression generally describe it as pleasurable and funny, not as an out-of-control anger. They might laugh while saying “I want to squeeze it!”, which is hardly what happens during real aggression. In fact, some therapists or counselors have playfully cited cute aggression when discussing how to manage overwhelming positive emotions, just to illustrate that sometimes even happiness needs regulating.

Managing extreme positive emotions is a relatively under-explored area in psychology compared to managing negative emotions. Cute aggression provides a tangible example: when “too happy,” our system may apply a bit of brakes by throwing in an opposite reaction. Some individuals might consciously or unconsciously do similar things (for instance, someone extremely excited about good news might suddenly become teary-eyed as a way to let off some steam). Recognizing these patterns can help individuals be more self-aware and accepting of their emotional processes. There’s no recommended “treatment” for cute aggression because it isn’t harmful by itself – if anything, it’s self-correcting. The only practical advice is common sense: channel the impulse safely. Squeeze a stress ball or pillow, use gentle pinching that doesn’t hurt, or simply vocalize the feeling (“You’re so cute I can’t even handle it!”). These expressions typically suffice to satisfy the urge. It’s similar to how people might stomp their feet when excited – a little physical release.

In summary, cute aggression is psychologically normal and even beneficial in moderation. It demonstrates how our emotion regulation can produce creative solutions (like an aggression-mimicking response to high happiness) to maintain balance. Individual differences exist, but neither experiencing nor not experiencing cute aggression is a cause for concern – it’s simply part of the diverse landscape of human affect. Clinically, investigating cute aggression further could yield insights into reward system function in different populations and emphasize that strong positive emotions, just like strong negative ones, require regulation. Above all, spreading awareness that wanting to squeeze something cute is both common and non-threatening helps destigmatize those strange thoughts and highlights the ingenious ways our brains keep us in check.

Conclusion

Cute aggression, the urge to enact seemingly aggressive behaviors in response to adorable cuteness, is a compelling example of a dimorphous emotional expression. Far from indicating actual anger or intent to harm, it represents the mind’s attempt to reconcile and communicate an overwhelming positive emotion. In this article, we explored how cute aggression is defined and studied, what neural circuitry underlies it, why it might have evolved, and how it appears in everyday life. Key findings suggest that when we see an extremely cute baby or animal, our brain’s reward systems (e.g., dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens) and emotion centers fire intensely, sometimes to the point of exceeding our typical comfort zone. In those moments, a playful aggressive impulse – expressed as gritted teeth, a desire to squeeze, or exaggerated words – may serve to regulate our joy, keeping us emotionally grounded and focused on caretaking tasks. Simultaneously, that dimorphous display signals to others the depth of our affection and our benign intentions (as paradoxical as pinched cheeks might seem, they really mean “I love this little thing!”).

We also saw that cute aggression likely carries adaptive value. Evolutionarily, it helps balance “cuteness-triggered caregiving” by preventing emotional overload and possibly by sharpening our awareness of an infant’s fragility. Across cultures and ages, people experience this phenomenon, whether they label it gigil or jokingly say “I could just eat you up.” Developmentally, it’s a testament to how even positive emotions can overwhelm children and adults alike, requiring an outlet. Real-world observations and experiments (like popping bubble wrap after seeing cute animals) confirm that the urge can translate into mild motor activity and that it is quite common. Crucially, cute aggression is not harmful – it remains an urge or symbolic act, and the actual care and gentleness people show toward cute beings indicate that the aggressive expressions are largely performative or internally modulatory.

In closing, cute aggression reaffirms that human emotions are complex and sometimes beautifully illogical. It reminds us that extreme happiness can resemble anger in its expression, not because the feelings are the same, but because the machinery of emotion regulation sometimes calls for opposite gears. For future research, many intriguing questions remain. Studies could further investigate neural pathways – for instance, using fMRI to see if any “braking” mechanisms activate during cute aggression or examining hormonal fluctuations (does oxytocin surge and then dip when the aggressive urge sets in?). Cross-cultural research could document how different societies express and interpret these urges, contributing to a global understanding of dimorphous expressions. Additionally, exploring populations with atypical emotional responses (such as neurodivergent individuals or those with affective disorders) might reveal nuances about when and how cute aggression manifests, potentially offering indicators of emotional processing strengths or difficulties.

Ultimately, cute aggression provides a lighthearted yet scientifically rich insight into the human condition. It highlights our capacity for immense affection – so much that it literally overflows – and the clever ways our brains ensure that affection doesn’t overwhelm us. So the next time you or someone you know exclaims, “That puppy is so cute I want to squeeze him!”, you can appreciate the sentiment for what it is: not a threat, but a quirky sign of love, regulated by the very wiring that makes us caring creatures. Our aggressive coos and playful pinches are, in their own way, nature’s guarantee that the cuter something is, the more devoted we are to preserving it.

References (Selected)

Aragón, O. R., Clark, M. S., Dyer, R. L., & Bargh, J. A. (2015). Dimorphous expressions of positive emotion: Displays of both care and aggression in response to cute stimuli. Psychological Science, 26(3), 259–273. [Read]

Glocker, M. L., Langleben, D. D., Ruparel, K., Loughead, J. W., Valdez, J. N., Griffin, M. D., & Gur, R. C. (2009). Baby schema modulates the brain reward system in nulliparous women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(22), 9115–9119. [Read]

Stavropoulos, K. K. M., & Alba, L. A. (2018). “It’s so Cute I Could Crush It!”: Understanding neural mechanisms of cute aggression. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 12, 300. [Read]

University of New South Wales (UNSW). (2024, February 2). Cute aggression: why you might want to squash every adorable thing you see. UNSW Newsroom. [Read]

Delbert, C. (2023, November 15). Want to bite that baby’s toes? Such ‘cute aggression’ may be key to our evolutionary survival. Popular Mechanics. [Read]

Know someone who would be interested in reading Cute Aggression Explained: Why We Want to Squeeze Adorable Things.

Share This Page With Them.

Go From "Cute Aggression Explained: Why We Want to Squeeze Adorable Things" Back To The Home Page