Interview with Wray Herbert

Want To Study Psychology?

Wray Herbert is an award-winning Washington, DC-based science journalist who has been communicating psychological science to the public for more than 25 years. He has been a reporter, writer and editor at Science News, Psychology Today, US News & World Report, and a regular columnist for Newsweek, Scientific American Mind, The Association for Psychological Science and The Huffington Post.

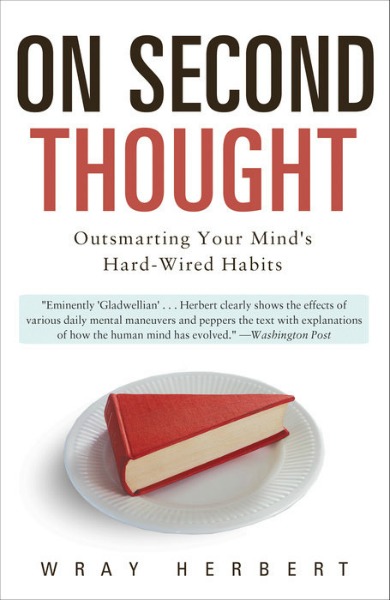

He is a fellow at the Carter Center for Mental Health Journalism, and the author of the highly acclaimed book 'On Second Thought: Outsmarting Your Mind's hard-Wired Habits.'

Q & A

You have been communicating psychological science to the public for more than 25 years. Do you think lay perceptions of psychology have changed much in that time?

(Keep It Real. Image by duncan c via flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

Look at your word choice here: psychological science, not psychology. Very few would have made that distinction 25 years ago, and it's a crucial distinction. Those of us who explain psychological science for a living face two major challenges. One is that readers equate psychology with therapy and life counseling-and with the worst kind of pop advice at that. There is very little science in what pop psychologists offer, or for that matter in what many professional psychotherapists offer. Don't get me wrong: There are many excellent therapists doing excellent work in helping people with serious mental and emotional problems, and the best therapies are informed by scientific insights into motivation, thinking, emotion and so forth. But psychological science shouldn't be confused with TV psychology.

The second challenge is that many people assume they already know how the mind works-and that the insights of science are obvious. Nobody assumes that they know immunology or particle physics, but everyone is a psychologist. So our job is above all to convince people that human behavior is complicated and mysterious and worth exploring in a rigorous way.

|

We've made tremendous progress in changing these misperceptions in the past 25 years. It's encouraging to see all of the talented behavioral science writers-many of them scientists themselves-who believe that it's important to boost the public understanding of the science. Scientists and journalists are no longer antagonists, at least not in the same way they once were, and this is a huge change. And as a result of this, consumers have become much more sophisticated. There is an unprecedented appetite today for the insights from psychological science. |

Find A Psychology School Near You

|

Which topic areas have you covered the most during your time writing about psychology?

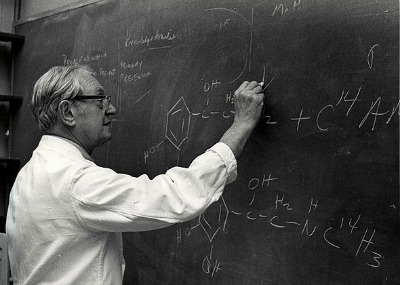

(Dr. Julius Axelrod)

That's changed over time, in an illuminating way. When I first started reporting on behavioral science and mental health, the psychoanalytic tradition was still fairly influential, as was behaviorism. But this was all about to shift. Julius Axelrod had just received the Nobel Prize for his work on the brain's catecholamine receptors, and within a few years neuroscience would dominate the enterprise-including the funding of research. I was a young reporter at Science News at the time, and it was a heady time for brain science. There really was a sense that these newly discovered brain chemicals held the key to understanding the mind and curing crushing diseases like schizophrenia and depression.

That didn't happen, of course. It's easy to be seduced by the brain, but no method of inquiry could fulfill all that promise. Neuroscience research has indeed yielded valuable insights into brain function and the malfunctioning mind, but these disorders remain stubbornly resistant to treatment. So gradually, the pendulum has swung back a bit, to the study of the basic psychological building blocks of the mind and behavior-memory, cognition, perception, attention. It's not possible to surgically divorce these mental capacities from the brain-this is widely accepted today-but neurons and chemicals are just one entryway to understanding the mind. Psychological science is another valuable entryway, and some of the richest insights today are coming from these disciplines.

If you had to choose one area of psychological science you have written about which seemed to resonate most with the public, what would it be?

I hope this doesn't trivialize the science or consumers. I would say that the public is fascinated by the quirks of the human mind. We like to think of ourselves as rational and logical and deliberate in the ways we conduct our lives, but we are often just the opposite. So much of our behavior is automated, and so many of our motives are subterranean. We make choices and judgments and decisions with the most irrational foundations, and our own irrationality fascinates us. It fascinates me.

To follow that up, in his review of your critically acclaimed book - On Second Thought: Outsmarting Your Mind's Hard-Wired Habits - Dan Ariely notes that you take readers "through a guided tour of our many irrational tendencies." The book is about heuristics. What exactly is a heuristic and which of these irrational tendencies do you personally find most fascinating?

A heuristic is a cognitive shortcut, a rule of thumb that allows us to make our myriad daily decisions more efficiently. Imagine you had to slow your mind down to deliberate every choice in your day—what brand of yogurt to purchase, whether to turn left or right, and so forth. You would be paralyzed. So we humans have over time acquired these tools to help us make some of our decisions automatically and rapidly. So this is a good thing—and one of the most robust findings to come out of a half century of cognitive psychology—but it can backfire. That’s really what my book is about—the backfiring. Some of these shortcuts were once adaptive, but no longer are in the modern world. Others are useful in one domain, but trip us up in other ways.

Let me give you an example, which is not in the book. University of Chicago scientists have identified a phenomenon they call “overearning,” which is the tendency to accumulate more and more in the way of wealth—far more than we have to. This may be a vestige of an early era of human evolution, a time when our ancestors frequently dealt with scarcity. It was to their advantage to work as much as possible and put resources by—hedging against the possibility of deprivation. Today, our survival is not so precarious, yet we still have this deeply rooted habit of mind, so we still keep accumulating resources—irrationally and mindlessly. It’s easy to see the practical implications, with the baby boomer generation hitting retirement age. Individual circumstances vary greatly, of course, but some may be missing out on new, late life experiences, out of an unjustified fear that they will run out of money.

To what extent do you intervene when you see friends and loved ones making irrational decisions, choices and judgments?

I don't - not at all. It's not in my nature to do that, but there is another reason I don't. Despite all the good science demonstrating these potent and surprising cognitive biases, there is far, far less evidence on how to trump them. Trying to talk ourselves out of irrational thinking isn't as easy as we might think, and in fact can backfire.

That said, there is some preliminary but promising work on countering problematic, negative biases in perception-seeing anger or threat where it does not exist. Such biases may play into disorders-antisocial behavior in the case of anger perception, anxiety disorders in the case of threat. If we can systematically train people away from these and toward more accurate judgments, that could be a useful intervention for some.

In your opinion is scientific knowledge of our mind's hard-wired habits being used more to inform or manipulate the public?

Both.

Madison Avenue has known about the familiarity heuristic forever. They just don't call it that. We prefer and trust anything that we know from repeated exposure. This is not new or shocking. Politicians know this too-which is why they keep repeating the "message" even if it's known to be factually misleading-Benghazi, Benghazi, Benghazi. Marketing folks also use the default heuristic, which basically is our mind saying: Why change if you don't have to? It takes cognitive effort to make a simple decision like switching brands, so we need a compelling reason to do so. So tobacco companies pitch their brands of cigarettes to new, young customers, and count on brand loyalty-their word for default heuristic-to keep them coming back.

But there is also some good work on using these biases for good. Most notably, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, in their book Nudge, describe what they call "soft paternalism"-making small changes in how people are offered choices in life. The idea to leverage these deep-rooted mental biases in order to "nudge" people toward better decisions-saving more money, making organ donations, that kind of thing. The Obama White House is very interested in this work, and in fact invited a group of psychological scientists in last year for a briefing on potential applications of this research.

Connect With Wray Herbert

Click Here to follow Wray Herbert on Twitter

Recent Articles

-

Neuropsychology

Dec 18, 25 04:16 AM

Neuropsychology information and resources. Learn all about the fascinating branch of psychology which explores the relationships between the brain and behavior. -

Psychology Articles by David Webb

Dec 16, 25 08:52 AM

Discover psychology articles by David Webb, featuring science-based insights into why we think, feel, and behave the way we do. -

Hedonic Adaptation Explained: Why Familiar Pleasures Lose Their Spark

Dec 16, 25 08:40 AM

Hedonic adaptation explains why pleasures fade over time. Learn how small changes can restore enjoyment and why popcorn tastes better with chopsticks.

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.Go To The Psychology Expert Interviews Page

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.