Psychology Classics On Amazon

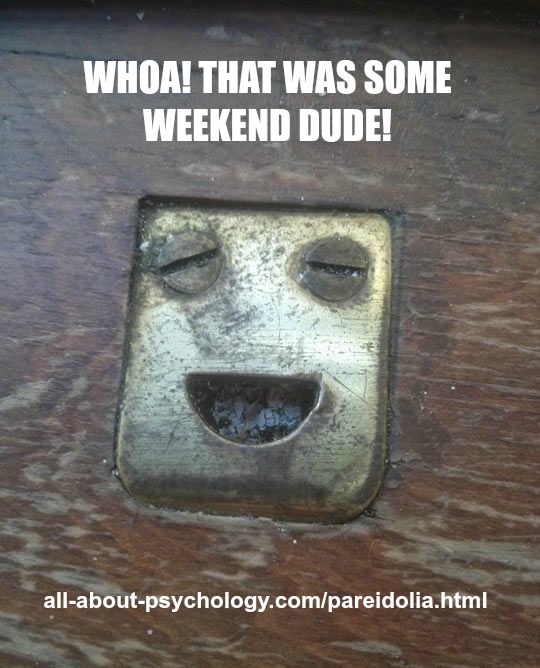

Holy Grilled Cheese Sandwich! What Is Pareidolia?

What do you see here: a tasty snack or a smiling face? (Image by jillmotts)

How much would you pay for a grilled cheese sandwich? $6? Maybe $7, if it was deliciously fresh and you were really hungry?

In 2004, Diane Duyser from Florida, USA sold a ten-year-old grilled cheese sandwich for US$28,000. And the reason for the 4,000-fold inflation?

This particular snack showed a pattern of browning that Ms. Duyser claimed resembled the Virgin Mary. Others agreed enough to create a news story that reached across the globe, piquing the interest of eBay bidders with deep pockets.

Religious icons have a habit of turning up in the most unlikely places. In recent years, the Virgin Mary has also been spotted in a pretzel that sold for US$10,600 and in a wooden stump near the cliffs in the Sydney suburb of Coogee (“Our Lady of the Fence Post”), while Mother Theresa has appeared in a cinnamon roll (the “Nun on a Bun”).

Meanwhile, Jesus has appeared many times, including in a pattern of mould in a bathroom (“Shower Jesus” – sold for US$1,999), and even the rear end of a three-year-old terrier.

Although devotees herald the blessings bestowed upon them by these apparitions (before selling to the highest bidder), science takes a more sober view, ascribing the phenomenon to coincidence, aided by a few quirks of neural processing that underlie our everyday perception. This is known as “pareidolia”.

Seeing patterns in noise

Pareidolia occurs when an indistinct and often randomly formed stimulus is interpreted as being definite and meaningful. This is something with which everyone has at least some experience, whether exercising their imagination as a cloud-gazing child, or seeing images in a textured ceiling during the last few waking moments of the day.

Examples in history abound. Indeed, Leonardo da Vinci remarked upon this technique to inspire artists, while Italian painter Arcimboldo was famous for portraits in which the faces were actually arrangements of food.

Although vision is most commonly involved, the other senses are not excluded.

Auditory pareidolia appears to be the most plausible explanation for the “backmasking” controversies of the 1980s, when rock bands were accused of embedding subliminal Satanic messages in their music, which were supposedly revealed when the tracks were played in reverse.

But why is this error of perception so prevalent, and why does it so often involve faces, and specifically those of religious icons?

The ubiquity of faces

There can be no doubt that faces, as visual stimuli, are somewhat special.

At the slightest glance, we can extract information on age, gender, race, and mood from a face, and decide whether this is a friend to be approached, or a foe to be avoided.

From birth, humans show a fascination with faces that continues throughout our lives.

Given that babies’ blurred vision serves to exclude more distant objects while the faces of family members and friends are thrust into view, it is not surprising that we all become face experts, training our brains to search for and identify faces in any situation.

As social animals, we constantly surround ourselves with faces, putting this skill to the test every day.

The neural basis of pareidolia

When presented with a stimulus, the human visual system uses information flowing in two different directions. These are referred to as “bottom-up” and “top-down” processes.

Bottom-up processing starts with the smallest possible element of the stimulus and builds in complexity. As collections of photons hit the receptors in our retinae, they are encoded as spots of colour.

These signals are combined across the image at the next levels of processing, where the brain uses templates to detect edges, then corners, basic shapes, and eventually objects (including faces).

An important brain region in the face detection process is an area in the brain’s temporal lobe known as the fusiform face area (FFA).

We have no conscious choice in the matter. The search for faces is automatic, using a coarse template roughly corresponding to the general configuration of a face (for example two eyes, side-by-side, above a nose, above a mouth).

The coarseness of this template means that we will very rarely miss a face that is presented to us, even if visibility is poor, but this also opens the possibility that it may be activated by similar patterns other than faces.

This contention is supported by functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) studies, which show significant FFA activation not only when faces are presented, but also when non-face stimuli are mistaken for faces.

It is likely that this activation is the neural basis of pareidolia.

Does religious thinking encourage pareidolia?

While the bottom-up neural machinery whirrs away, top-down processes flow in the opposite direction.

Here, the perception of a stimulus can be affected by an observer’s knowledge, expectations, beliefs and motivations.

Although these factors are harder to measure, they can undoubtedly have an influence over what we see, and seem to play a prominent role in pareidolia.

The Rorschach inkblot test is a well-known example of using pareidolia to tap into motivations, emotional functioning, and other higher-level psychological characteristics.

Although pareidolic experiences are commonly reported during schizophrenic episodes and during the use of hallucinogens such as LSD, all “normal” people also experience this illusion on some level.

But there are some groups who are especially susceptible.

A 2012 study from Finland showed that those with strong religious beliefs, or belief in the paranormal were more likely to identify a face in a random stimulus compared to sceptics or non-religious observers.

It seems likely their low threshold for pareidolia is a factor in the large number of examples that involve historical religious figures.

In addition, many of the faces that are often reported, such as Jesus and the Virgin Mary, are individuals who predate photography, and whose facial identity cannot be known, other than through iconography.

As such, the stimulus could match any one of many possible representations of Jesus or the Virgin Mary, making such apparitions more likely still.

Miracle or coincidence? You be the judge

Given the massive array of random stimuli human beings could possibly be exposed to, it is inevitable that some of them will bear a degree of similarity to certain non-random visual patterns, such as faces.

In these cases, it is not surprising that the brain activity caused by the face itself and the coincidentally similar visual pattern will be closely related, leading our rough and ready face templates to be matched, and for the brain to detect a face where there is none.

Coincidences happen. It would be truly amazing if they never did.

![]() But then, who would notice?

But then, who would notice?

Kevin Brooks, Senior Lecturer in Human Visual Perception, Macquarie University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Learn More About Pareidolia

See following link to learn all about pareidolia, the psychological phenomenon that makes us see faces in random places!

Want To Read More Great Psychology Articles?

See following link to check out a fascinating collection of psychology articles by leading academics and researchers.

Recent Articles

-

Cool People: What Psychology Reveals About Their Global Appeal

Jul 06, 25 12:54 PM

What makes cool people so magnetic? Discover the science behind their traits and why they're admired across cultures - according to global psychology research. -

Sponsor a Psychology Website with Over a Million Yearly Visitors

Jun 30, 25 11:30 AM

Showcase your brand to a huge, engaged audience. Discover how to sponsor a psychology website trusted by over a million visitors a year. -

Unparalleled Psychology Advertising Opportunities

Jun 29, 25 04:23 AM

Promote your book, podcast, course, or brand on one of the web's leading psychology platforms. Discover advertising and sponsorship opportunities today.

Please help support this website by visiting the All About Psychology Amazon Store to check out an awesome collection of psychology books, gifts and T-shirts.