Psychology Classics On Amazon

The Surprising Benefits of Being a Pessimist

Cartoon by Reza Farazmand

How many times have you been told that something great will happen as long as you believe it is possible? From pop psychology books to self-improvement seminars and blogs, there’s a lot of hype surrounding the advantages of positive thinking. And there’s certainly some evidence behind it – a large body of work suggests that being optimistic reaps a number of positive rewards, including better health and wellbeing.

But what about the people who tend to see the glass as half empty rather than half full? Is being pessimistic always such a bad thing? Actually, the latest research suggests that some forms of pessimism may have benefits.

Pessimism isn’t just about negative thinking. Personality science has revealed it also includes a focus on outcomes – that is what you expect will happen in the future. While optimists expect positive outcomes will happen more often than not, pessimists expect negative outcomes are more likely.

There is a particular type of pessimist, the “defensive pessimist”, who takes this negative thinking to a whole new level and actually harnesses it as a means for reaching their goals. Research has shown that this way of thinking can not only help them succeed, but also bring some rather unexpected rewards. However, the other main form of pessimism, which involves simply blaming oneself for negative outcomes, has less positive effects.

Performance and confidence

But how does defensive pessimism actually work and what benefits can you expect to get out of it? Researchers suggest that defensive pessimism is a strategy that people who are anxious use to help them manage their anxiety, which might otherwise make them want to run in the opposite direction of their goal rather than pursue it.

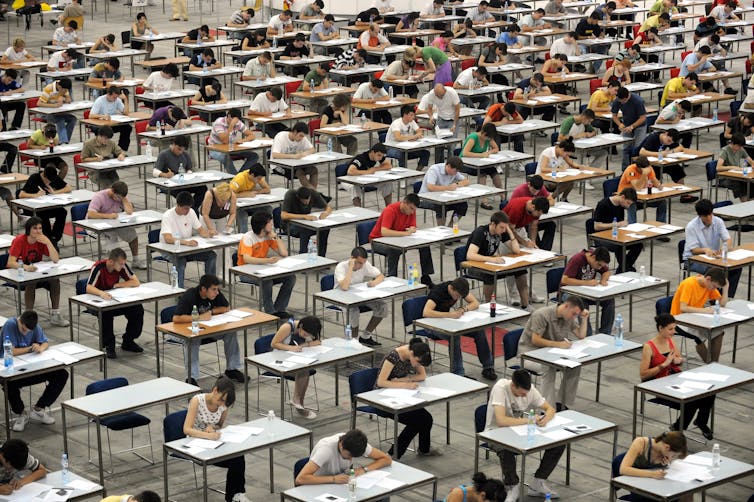

The crucial factor is setting low expectations for the outcome of a particular plan or situation – like expecting that you won’t get hired after a job interview – and then envisioning the details of everything that might possibly go wrong to make these worst-case scenarios a reality. This gives the defensive pessimist a plan of action to ensure that any imagined mishaps won’t actually happen – such as practising for the interview and getting there early.

The benefits of defensive pessimism also extends to actual performance. One study shows that this has everything to do with negative mood. When prompted to be in a good mood, defensive pessimists performed poorly on a series of word puzzles. However, when they were put in bad mood, by being instructed to imagine how a scenario might have negative outcomes, they performed significantly better. This suggests that they harness their negative mood to motivate themselves to perform better.

Pessimism can also be more beneficial than optimism in situations where you are waiting for news about an outcome and there is no opportunity to influence the outcome (such as waiting for the results of a job interview). When the outcome is not as good as optimists had hoped for, they take a bigger hit to their wellbeing and experience greater disappointment and negative mood than do your garden-variety pessimists.

Strangely, this type of pessimism can even help boost confidence. In one study that followed students throughout their university years, those who were defensive pessimists experienced significantly higher levels of self-esteem compared to other anxious students. In fact, their self-esteem rose to almost the levels of the optimists over the four years of the study. This may be due to increases in the defensive pessimists’ confidence to anticipate and successfully avoid the negative outcomes they imagined.

Health

The defensive pessimist’s strategy of being prepared to prevent negative outcomes can also have some very real health benefits. Although these individuals will worry more about getting ill during an outbreak of an infectious disease compared to optimists, they are also more likely to take preventive action. For example, they might frequently wash their hands and seek medical care promptly when they experience any unusual symptoms.

When pessimists become chronically ill, their negative view of the future may be more realistic and encourage the sort of behaviours that healthcare professionals recommend for managing their illness. I conducted a study with two groups of people – those with either inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or arthritis – and asked them to rate their future health on a simple scale ranging from poor to excellent. Because both arthritis and IBD are long-term health conditions that often worsen over time you wouldn’t expect people to think their health would improve that much in the future.

However, those who were optimists still rated their health as improving in the future, whereas the pessimists saw their health as getting worse in the future. Taking this view may lead pessimists to engage in the types of coping strategies necessary to manage symptoms such as pain. Having said that, this benefit may be best realised when there is at least some optimism that such strategies will actually work.

The key difference that separates defensive pessimists from other individuals who think negatively – such as those who are simply anxious or depressed – is the way they cope. Whereas people tend to use avoidance to cope with anticipated problems when they are feeling anxious or depressed, defensive pessimists use their negative expectations to motivate them to take active steps to feel prepared and be more in control over outcomes.

So being a pessimist isn’t necessarily bad – though you may irritate others. Ultimately, it’s what you do with that pessimism that matters.

Are you a defensive pessimist? Answer these questions to find out.![]()

Fuschia Sirois, Reader in Health Psychology, University of Sheffield

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Recent Articles

-

Sponsor a Psychology Website with Over a Million Yearly Visitors

Jun 30, 25 11:30 AM

Showcase your brand to a huge, engaged audience. Discover how to sponsor a psychology website trusted by over a million visitors a year. -

Unparalleled Psychology Advertising Opportunities

Jun 29, 25 04:23 AM

Promote your book, podcast, course, or brand on one of the web's leading psychology platforms. Discover advertising and sponsorship opportunities today. -

Psychology Book Marketing

Jun 29, 25 04:19 AM

Psychology book marketing. Ignite your book's visibility by leveraging the massive reach of the All About Psychology website and social media channels.

Please help support this website by visiting the All About Psychology Amazon Store to check out an awesome collection of psychology books, gifts and T-shirts.