The Eyes, They (Sometimes) Lie

Eyewitness Accounts, Unreliable Senses, and the Role of Witnessing in Establishing Truth.

Curing Crime, Christian Orlic, Lucas Heili

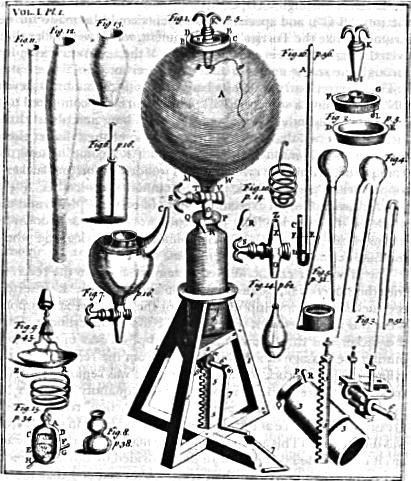

The Eye: Our Window Into the World. Source

Seeing is Believing. At least, that is what many think. Witnessing events and demonstrations has, for a long time, been seen as one of the most substantial kinds of evidence. Alleged eyewitness accounts are the foundation of many religions. Witnessing has been highlighted in resolving early scientific disputes and is still seen as trustworthy. Criminal justice systems have often relied on eyewitness accounts to determine whether someone is guilty. Sadly, eyes and memories are relatively poor at producing accurate accounts and thus unreliable in determining truth.

Science, “Truth,” and Witnessing

Simon Schaffer and Steve Shapin wrote a seminal book on the history of science, which explored a debate on what should be counted as knowledge. These historians studied a debate between Hobbes and Boyle over the existence of vacuums. The stakes, however, were much more significant: how do people produce knowledge about the world? This discussion, which Boyle won, established the importance of witnessing and authority in determining what counts as fact. Schaffer and Shapin argued this was a foundational point in the modern world. They posited that what human societies know is mainly due to political organization. Boyle emphasized experiments, public demonstrations, and witnessing as essential in producing knowledge, whereas Hobbes sustained that logic and deductive reasoning were more appropriate than experiments in understanding nature.

One of the most prominent points of contention between Boyle and Hobbes was what it meant to make knowledge publicly accessible. Hobbes argued that anyone could do science anywhere. For him, it was about using deduction and thought to investigate the world. Hobbs held that these ideas could be shared with the public via writings and debates. In contrast, Boyle held that knowledge was best produced when reliable and respected thinkers could witness an experiment/demonstration. For Boyle and his supporters, credible witnesses had to attest to experiments and demonstrations for these to be believable. In short, these witnesses gave the experiment authority. According to this view, witnessing produced reliable and accurate knowledge if two conditions were met. First, spaces had to be accessible to reliable witnesses. Second, the accounts needed to be credible. Thus, it produced a public space with restricted access, given that only reliable witnesses could access it. These witnesses were expected to be impartial, educated, and trustworthy.

Boyle’s Air pump. Source

Boyle dealt with criticism from within this space differently from those who criticized the existence of such spaces. Boyle sought to erect a wall between experimentalists and those concerned with matters of the state. Experimentalists, like Boyle, argued that free men could associate and resolve disputes within these areas in contrast to Hobbes, who held that such spaces would indubitably sway as their master demanded. The experimentalists argued their work was valuable because it could be applied to address concurrent issues. Hobbes found experiments artificial and thus, by their very nature, unable to unveil the nature of the world.

Schaffer and Shapin concluded that Boyle’s ideas and ways to produce knowledge won because they jived with restoration policies and concerns. They claimed that experimental science succeeded because it could form a consensus among practitioners and the public. Moreover, this view was compatible with emerging political ideals. Thus, the rise of experimental science is not a reflection of reason but rather the result of social processes. Such processes also cemented the power of eyewitness accounts.

Eyewitness and Criminal Justice

Eyewitness accounts have played an immense role in criminal justice. At first glance, this makes sense since, unlike the jury (or judge), these people were at the scene of the crime. One can imagine that the next best thing would be to ask for the testimony of someone present. Our subjective experience suggests we can recall events and those involved with significant events.

Nevertheless, eyewitness accounts are less reliable than one might think.

Dr. Jason Frowley, a professor of criminal psychology, wrote an article where he explored how overconfidence quite often affects the decisions made by jurors in trials.

Frowley provided the following definition: “Our confidence in our own judgment doesn’t rely as heavily as we might like to think on the quality or quantity of the evidence in front of us.” It seems other factors are more important such as whether information “flows together to create a coherent, believable story” (Frowley). Witnesses, jurors, and others are susceptible to this effect.

We wish memory could be more reliable, and the metaphor people often use misconstrues what neuroscience has revealed. Our memories are not like re-streaming an episode we’ve watched tens of times. Instead, a more apt metaphor is that they are like paintings or movies we recreate each time we remember. With each production, slight changes can sweep in. Frowley asked his readers to “Imagine an eyewitness to a short, brutal crime that occurs unexpectedly, under conditions of less-than-perfect visibility” (Frowley). If this person is asked to recall the events of the crime, their recollections will change over time. If asked months later, their account might as well be the plot of a crime thriller novel, regardless of how much effort they put into honestly recounting events. Frowley continued - “Everything counts against them. They were not prepared, … and may immediately have thought more of their own safety than trying to memorise details of height, weight, and clothing. Shock hardly helps the memory either” (Frowley).

Studies suggest that eyewitness accounts are rather terrible. Timothy Cole was exonerated through DNA in 2009 after being convicted of rape in 1986. One of his alleged victims identified him three different times: in two different lineups and during his trial (Lithwick, 2009). The actual rapist had been bragging about these rapes for over a decade. A 2009 study looking into some 200 overturned convictions found that eyewitness accounts played an essential role in the trials of over 70% of convicted people who were later exonerated by DNA (Lithwick, 2009).

There are other cases in which eyewitnesses identified the wrong suspect. In 1984 Jennifer Thompson was 22, one night she was assaulted and raped. She claimed that throughout this horrific episode, she carefully and methodically studied her assailant. Thompson was determined to help prosecute him if she survived. She reported the assault to the police and subsequently identified Ronald Cotton in a physical lineup. Policemen were impressed by how composed and certain she was.

A few days later, the police called her back so she could see another lineup of possible suspects. This time, she hesitantly picked Cotton out of a different lineup. The cops informed her she had chosen the same individual. One potential issue with such lineups is that they make it seem like the assailant must be one of the six people in them. In this case, Thompson’s actual rapist was not even in the lineup. She identified the same individual twice and claimed she was pleased to have done it right. Ten years later, DNA evidence exonerated Cotton. The same DNA evidence helped the authorities identify the actual rapist. When she saw him, she thought she had never seen him before.

Later, Thompson befriended Cotton, and today, they travel around the United States, exposing the unreliability of eyewitness accounts. They wrote a book and gave speeches together to raise awareness about the shortcomings associated with eyewitness accounts.

Eyewitness accounts are unreliable.

Optical Illusions, Conjurors, and Our Silly Senses

Optical Illusion, Source

Magicians, mentalists, and conjurors (warlocks and witches, if you will) have known for a long time that our senses are incredibly unreliable. They amaze us because they do the seemingly impossible. Tens of thousands of people attend shows where they witness events that defy explanations. Responsible showpeople like Derren Brown are honest about their dishonesty.

Our senses are the only way we can access the world, so how else could we learn about it? Nevertheless, it is imperative to recognize that our eyes are unreliable, our hearing can be tricked into hearing what's not there, and our memory is flawed. There might be no clearer or better proof of the unreliability of our senses than magic and optical illusions. The latter shows just how poor our eyes are.

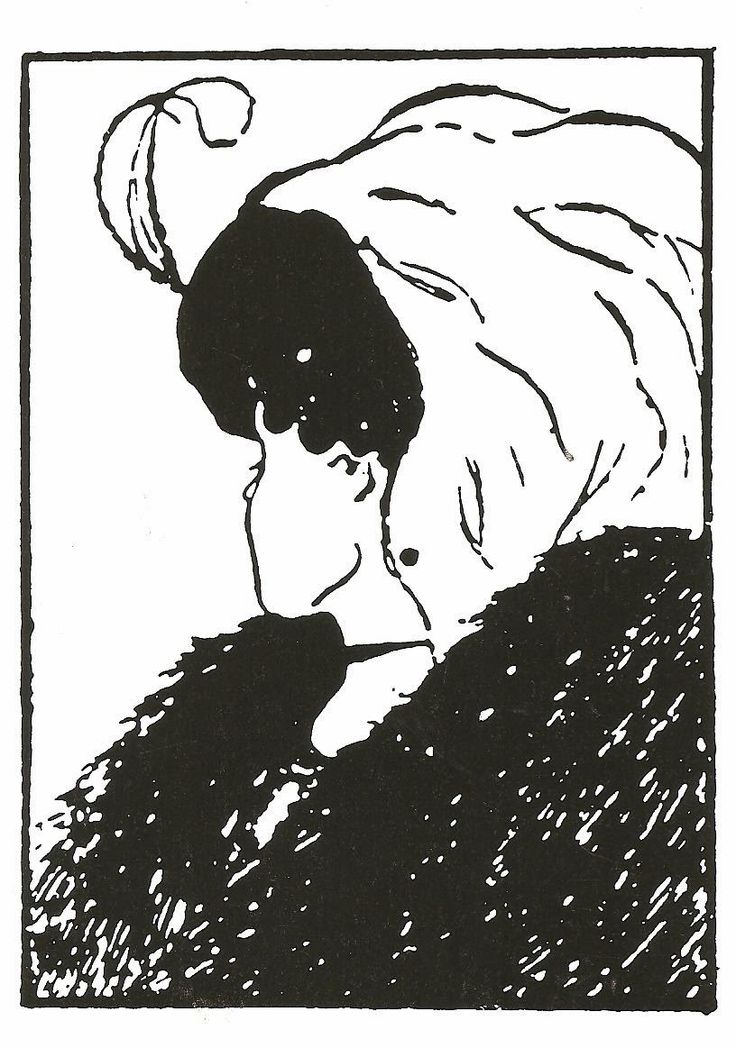

A gestalt illusion, where the image shifts between two models. In this case an old and young woman. (Source)

Illusions are often described as a “discrepancy between perceived reality and objective physical reality” (Gillan, 1990). Optical illusions are quite entertaining to play around with.

Unfortunately, they hinder the credibility of our recollection of reality. When combined with an imperfect memory, the slightest changes in lightning, perspective, distance, or mental state can dramatically change our perception of events. In that case, the result is a sketchy judgment, at best. Further, each time we remember, our memory may slightly change.

Conclusions

Witnessing has long been considered a gold standard form of evidence, but it is not. Schaffer and Shapin argued that Boyle’s debate with Hobbs did a lot to cement the primacy given to witnessing as a means to establish truth. Modern findings, science, magicians, and optical illusions are stark reminders that our untamed senses are poor at distinguishing what is from what appears to be. The importance given to eyewitness testimonies by criminal justice systems has resulted in the wrongful conviction of hundreds of individuals. It is time that such testimonies are correctly problematized.

In this view, V-Sauce further explores the problems with eye-witness accounts. It is well worth a watch.

Building just societies requires strong institutions and a commitment to doing better. While we have urged caution in the overzealous adoption of scientific, medical, and technocratic solutions to social problems, cautious adoption is a decent approach. In this case, it is time to increase our evidence standards. It is time that we recognize the limits of our senses. It is time to think seriously about how to best reform the criminal justice system.

Sources

Lithwick, D. 2009. Have the Eyes Had it? Slate, March 14, 2009. https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2009/03/is-our-eyewitness-identification-system-sending-innocents-to-jail.html

Gillan, 1990. Illusions at Century End. Chapter 5 in Perception and Cognition at Centruy’s End. https://www.sciencedirect.com/sdfe/pdf/download/eid/3-s2.0-B9780123011602500071/first-page-pdf

EPI 390 Michigan State University Lecture Notes.

And Cited Sources. Christian also read the book Cotton and Thompson authored together.

Authors: Christian Orlic & Lucas Heili collaborated to produce this article.

Want to read more great articles by these authors? Subscribe to their fascinating newsletter Curing Crime.

For students and teachers of psychology, Curing Crime offers a fascinating historical and ethical perspective on the intersection of science, medicine, and criminal behavior, making it a must-read for anyone interested in forensic psychology and the psychology of crime.

Know someone who would love to read The Eyes, They (Sometimes) Lie?

Share This Page With Them.

Go From The Eyes, They (Sometimes) Lie Back To The Home Page