The Terrifying Power Of Stereotypes –

And How To Deal With Them

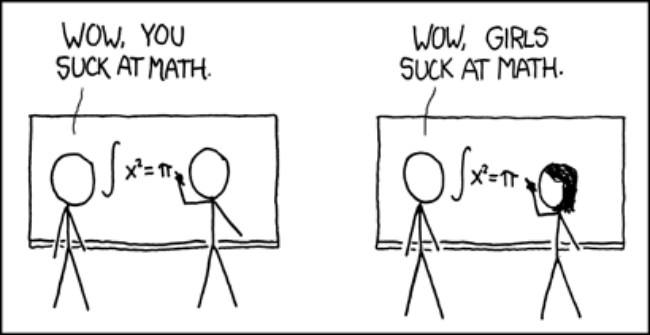

(Image by Randall Munroe via xkcd.com)

From “girls suck at maths” and “men are so insensitive” to “he is getting a bit senile with age” or “black people struggle at university”, there’s no shortage of common cultural stereotypes about social groups. Chances are you have heard most of these examples at some point. In fact, stereotypes are a bit like air: invisible but always present.

We all have multiple identities and some of them are likely to be stigmatised. While it may seem like we should just stop paying attention to stereotypes, it often isn’t that easy. False beliefs about our abilities easily turn into a voice of self doubt in our heads that can be hard to ignore. And in the last couple of decades, scientists have started to discover that this can have damaging effects on our actual performance.

This mechanism is due to what psychologists call “stereotype threat” – referring to a fear of doing something that would confirm negative perceptions of a stigmatised group that we are members of. The phenomenon was first uncovered by American social psychologists in the 1990s.

In a seminal paper, they experimentally demonstrated how racial stereotypes can affect intellectual ability. In their study, black participants performed worse than white participants on verbal ability tests when they were told that the test was “diagnostic” – a “genuine test of your verbal abilities and limitations”. However, when this description was excluded, no such effect was seen. Clearly these individuals had negative thoughts about their verbal ability that affected their performance.

Black participants also underperformed when racial stereotypes were activated much more subtly. Just asking participants to identify their race on a preceding demographic questionnaire was enough. What’s more, under the threatening conditions (diagnostic test), black participants reported higher levels of self doubt than white participants.

Nobody’s safe

Stereotype threat effects are very robust and affect all stigmatised groups. A recent analysis of several previous studies on the topic revealed that stereotype threat related to the intellectual domain exists across various experimental manipulations, test types and ethnic groups – ranging from black and Latino Americans to Turkish Germans. A wealth of research also links stereotype threat with women’s underperformance in maths and leadership aspirations.

Men are vulnerable, too. A study showed that men performed worse when decoding non-verbal cues if the test was described as designed to measure “social sensitivity” – a stereotypically feminine skill. However, when the task was introduced as an “information processing test”, they did much better. In a similar vein, when children from poorer families are reminded of their lower socioeconomic status, they underperform on tests described as diagnostic of intellectual abilities – but not otherwise. Stereotype threat has also been shown to affect educational underachievement in immigrants and memory performance of the elderly.

It is important to remember that the triggering cues can be very subtle. One study demonstrated that when women viewed only two advertisements based on gender stereotypes among six commercials, they tended to avoid leadership roles in a subsequent task. This was the case even though the commercials had nothing to do with leadership.

Mental mechanisms

Stereotype threat leads to a vicious circle. Stigmatised individuals experience anxiety which depletes their cognitive resources and leads to underperformance, confirmation of the negative stereotype and reinforcement of the fear.

Researchers have identified a number of interrelated mechanisms responsible for this effect, with the key being deficits in working memory capacity – the ability to concentrate on the task at hand and ignore distraction. Working memory under stereotype threat conditions is affected by physiological stress, performance monitoring and suppression processes (of anxiety and the stereotype).

Neuroscientists have even measured these effects in the brain. When we are affected by stereotype threat, brain regions responsible for emotional self-regulation and social feedback are activated while activity in the regions responsible for task performance are inhibited.

In our recent study, published in Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, we demonstrated this effect for ageism. We used electroencephalography (EEG), a device which places electrodes on the scalp to track and record brainwave patterns, to show that older adults, having read a report about memory declining with age, experienced neural activation corresponding to having negative thoughts about oneself. They also underperformed in a subsequent, timed categorisation task.

Coping strategies

There is hope, however. Emerging studies on how to reduce stereotype threat identify a range of methods – the most obvious being changing the stereotype. Ultimately, this is the way to eliminate the problem once and for all.

But changing stereotypes sadly often takes time. While we are working on it, there are techniques to help us cope. For example, visible, accessible and relevant role models are important. One study reported a positive “Obama effect” on African Americans. Whenever Obama drew press attention for positive, stereotype-defying reasons, stereotype threat effects were markedly reduced in black Americans’ exam performance.

Another method is to buffer the threat through shifting self perceptions to positive group identity or self affirmation. For example, Asian women underperformed on maths tests when reminded of their gender identity but not when reminded of their Asian identity. This is because Asian individuals are stereotypically seen as good at maths. In the same way, many of us belong to a few different groups – it is sometimes worth shifting the focus towards the one which gives us strength.

Gaining confidence by practising the otherwise threatening task is also beneficial, as seen with female chess players. One way to do this could be by reframing the task as a challenge.

Finally, merely being aware of the damaging effects that stereotypes can have can help us reinterpret the anxiety and makes us more likely to perform better. We may not be able to avoid stereotypes completely and immediately, but we can try to clear the air of them.![]()

Magdalena Zawisza, Senior Lecturer in Psychology, Anglia Ruskin University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Want To Read More Great Psychology Articles?

See following link to check out a fascinating collection of psychology articles by leading academics and researchers.

Recent Articles

-

Psychology Articles by David Webb

Dec 14, 25 05:05 AM

Discover psychology articles by David Webb, featuring science-based insights into why we think, feel, and behave the way we do. -

Schadenfreude Explained: Why We Enjoy Others’ Missteps

Dec 14, 25 04:54 AM

Schadenfreude explains why we sometimes enjoy others’ misfortunes. Explore the psychology behind this emotion, from social comparison to moral judgment. -

What Is Antifragility? Why It Matters in an Unpredictable World

Dec 11, 25 07:58 AM

Discover what antifragility means, how it differs from resilience, and why small challenges help us grow stronger in an uncertain world.

Please help support this website by visiting the All About Psychology Amazon Store to check out an awesome collection of psychology books, gifts and T-shirts.