Interview With Dr Sohom Das

Dr Sohom Das (MBChB, BSc, MSc, MRCPsych) is a Consultant Forensic Psychiatrist who lives and works in London. This niche specialism involves the crossroads of offending and severe mental illness. In his role, Sohom assesses and rehabilitates mentally disordered offenders in prisons, courts and in special secure psychiatric units, such as Broadmoor Hospital, that are reserved for the most dangerous and violent mentally ill patients. He is an experienced expert witness, who regularly provides evidence in Criminal Court, including the Old Bailey.

Sohom hosts a YouTube channel, named ‘A Psych for Sore Minds’, and posts at least 2 videos every week. He dissects a variety of mental health issues and proffers his own opinions. Some episodes are related to offending, such as diagnosing and working with psychopaths, prisoners faking mental illness and his personal analysis of high-profile mentally ill criminals (such as the Yorkshire Ripper). Other videos address more common psychiatric issues, such as exploring individual diagnoses, the process of being sectioned, life on a psychiatric unit, and answering his viewers’ questions. Sohom also interviews a variety of guests about their experience of mental illness; this has included previous patients, an ex-prisoner and a police officer who has suffered trauma in the line of duty.

What led you to pursue a professional interest in forensic psychiatry?

I have always had a fascination with gangs and violence from listening to gangsta rap and watching violent movies as a youngster. Going into medical school, I had no idea that there was a field that would accommodate these morbid tastes! When I qualified as a doctor, I stumbled into psychiatry whilst living in Australia (where I had gone to work in Accident and Emergency) and fell in love with it immediately. There's something fascinating about stepping into the delusional world of people suffering with psychosis. Also, there's something fulfilling about supporting people at their lowest ebb, such as after suicide attempts. I did a forensic placement as a junior doctor on a whim, not knowing very much about this particular sub-subspecialty. I found assessing and rehabilitating mentally disordered offenders in courts, prisons and secure psychiatric units (such as Broadmoor Hospital) reserved for the most dangerous psychiatric patients even more captivating. All the subjects I see have a multitude of reasons why they have ended up with a severe mental illness and stuck in a life of crime. This is usually a mixture of various traumas, poverty, abuse, addiction and poor parenting. I love piecing together the puzzle to figure out why they have ended up where they are.

Can you tell us about one particular case which has affected you?

One of the very first experiences I had of acting as an expert witness was a tragic case of an 18-year-old schoolgirl who had no previous offending or signs of mental illness. She became floridly psychotic within the space of a couple of weeks and tragically she killed her three-year-old nephew whilst babysitting him; she smothered him with a pillow. She was completely delusional at the time and believed that she was ridding him of demons and could reincarnate him. Obviously, it was a horrific crime and had catastrophic consequences for the whole family, but she really had zero criminal culpability at the time. I assessed her in prison and upon my evidence at the Old Bailey, got her transferred to a psychiatric unit for offenders, under a criminal section of the Mental Health Act; whereas the prosecution were pushing for a life sentence in prison.

It was a very emotionally charged experience, not only due to the nature of her offence, but the whole process of observing her gradually recover from psychosis when we enforced treatment on her against her will. She came to the gradual realisation of what she had done, which was heart-breaking to witness. I also spoke to her brother (the father of the victim) regularly for family therapy.

As well as all the emotion, purely looking at it from a medico-legal standpoint, it was very educational for me. I was a middle grade Specialist Registrar at the time, near the beginning of my higher training. I had the opportunity to give evidence at the Old Bailey for the defences of 'diminished responsibility' and also 'not guilty by reason of insanity'.

In terms of having an accurate grasp of your profession, how would you rate public understanding of forensic psychiatry?

I have to say that forensic psychiatry is quite a furtive world. Many of my peers don't like disclosing to the public what goes on behind the locked, magnetic, industrial strength doors of their secure psychiatric wards. Consequently, there is a lot of misunderstanding about what we do and who we treat. For example, Forensic Psychiatrists have absolutely no involvement in solving crimes. We rehabilitate, assess and treat mentally disordered offenders after they have committed crimes and we give expert evidence in court.

I think people assume that we sit with murder suspects and try to catch them out through some verbal sparring game of mental chess. Similarly, criminal profiling is a very contentious issue. Some Forensic Psychologists might do this but there is no scientific basis behind it.

Another misunderstanding I think is that our patients are all 'bad' or 'evil' people to a certain extent. In reality, although we have some hostile and difficult people (for example, with Anti-social Personality Disorder), we also have clients on the other end of the spectrum who are not pro-criminal or violent at all. They have suddenly become floridly psychotic and committed one inexplicable horrific act of violence (including killing their relatives) which is completely out of character from their baseline selves.

What is the difference between forensic psychiatry and forensic psychology?

Psychiatrists are medical doctors; we have certain responsibilities and tasks that psychologists cannot do, such as prescribing medication and sectioning people. Forensic Psychologists are more about talking therapy. They generally tend to have a lower caseload but have more time to sit with each individual patient. Generally speaking, psychiatrists deal with mental illness such as schizophrenia or mania, whereas psychologists deal with the breakdown of personality. There is a massive overlap, obviously.

What would you say is the most rewarding and the most challenging aspect of the work you do?

I would argue that we have limited direct job satisfaction. This is because we often detain patients against their will, while they are at their lowest ebb, and medicate them when they have no insight. Our measure of success is not seeing our patients again. I very rarely get a "thank you" from our patients. They are just relieved to leave our hospital. In a similar way as I imagine most prison officers don't get thanks, nor do traffic wardens! We also have to deal with aggressive and threatening patients routinely.

However, there are times when I have given expert evidence in cases, including murder cases, where I think the perpetrator is extremely unwell and needs to be treated and rehabilitated for their mental illness as opposed to punished in prison (just like the young lady I mentioned above). My court reports and cross-examination in the witness stand have swayed the judge. In my own way I like to think that I have saved some mentally ill people from many years in prison, and redirected them for long-term rehabilitation, in view of one day allowing them to be re-integrated into society, in a far less dangerous state than when they were admitted to psychiatric hospital.

One challenging aspect of the job is when the opposite of this happens. It is very frustrating when judges occasionally completely ignore my expert evidence; usually because they have already made up their mind about a case. For example, there have been a few times in my career where I have arranged a Mental Health Act assessment to section somebody to a secure unit because they are clearly psychotic. But the judge doesn't seem to want to look past the troubling nature of their crime and has sentenced them to prison instead. Although there are psychiatric services in prison (and I have worked for some of these myself), they are nowhere near as effective or thorough as inside secure psychiatric units. It seems almost cruel for the perpetrator (despite the offence they may have committed) to be unnecessarily suffering from severe mental illness and not receiving the treatment they need.

What can viewers expect from your YouTube channel A Psych for Sore Minds?

My channel is and eclectic mix of videos related to mental illness, offending (particularly violence), and the crossroads between the two worlds. Often, it's basically me talking about various aspects of my job. I sometimes scrutinise high-profile criminal cases (such as the Unabomber, Charles Bronson and Ronnie Kray) and undertake my own personal psychoanalysis. My USP is talking about my own cases (anonymised of course). I also interview various people who have experience of mental health issues or the criminal justice system, such as people who have been sectioned in the past and ex-prisoners. I also answer viewers' questions related to both mental illness and criminality in some videos.

Of all the true crimes you cover on A Psych for Sore Minds, which one do you personally find most interesting and why?

I am fascinated by the case of Andrea Yates. Her story has some eerie echoes of the case I mentioned above of the young woman who killed her nephew. Andrea was a nurse who suffered post-partum psychosis and killed all of her five children while floridly psychotic in Houston in 2001. As I explain in depth in my episode, the medico-legal process was tainted by the expert evidence of a fellow Forensic Psychiatrist. As I frequently give evidence in criminal trials, this strikes close to home for me. It annoyed and frustrated me to learn about the very basic mistakes this renowned colleague made - it led to Andrea being charged for murder, until she had a retrial years later, and was then transferred for treatment in a secure psychiatric unit, where she should have been sent in the first place.

As someone who has assessed hundreds of patients in prisons and secure psychiatric wards, what are the most common forensic mental health disorders you come across?

The majority of patients in prison have some kind of personality disorder. Anti-social Personality Disorder is the most common; it is associated with a disregard to the rights of other people and the law, a lack of empathy, not learning from previous lessons and, a low threshold for anger and hostility. These people, generally speaking, tend to be career criminals who have a felonious lifestyles; such as being drug dealers or repeat burglars. The next most common would be Borderline Personality Disorder which is associated with extreme emotional outbursts and unstable moods, as well as self-harming and issues with personal identity. From my experience, people with this disorder don't intend to offend (like people with Anti-social Personality Disorder) but they lose their temper excessively and suddenly. They act out dramatically, occasionally with violence, and then regret their actions afterwards.

When we talk about patients in secure psychiatric units, who have been sectioned under criminal sections of the Mental Health Act, the most common illness is schizophrenia. Although the vast majority of people with this diagnosis are not violent, a small cohort are; they tend to hear voices, such as command hallucinations which tell them to attack other people. Alternatively, they have paranoid delusions such as the belief that random people are following them, mocking them or even want to kill them. They understandably lash out pre-emptively, sometimes in an aggressive manner. Although this is generally rare, it is exactly the kind of presentation that leads them to be sectioned. The good news is that their future risk can be decreased significantly with rehabilitation and treatment; much easier than somebody with entrenched personality flaws such as Anti-social Personality Disorder.

Which mental health/personality disorder fascinates you the most?

I would have to say clinical psychopathy. I like to think of this as the bigger brother of the aforementioned Anti-social Personality Disorder. The former includes extra traits, such as being extremely charming, manipulative, deceitful and cunning. Psychopaths see everybody as an opportunity to exploit in some way. I have worked with a couple of psychopaths (and even worked for one!); and have made a series of videos about them on my YouTube channel.

How common is it for offenders to fake mental illness?

This is also a series on my channel! For the psychiatric assessments I carry out as an expert witness for criminal court, I see people who either fake or exaggerate mental illness (i.e. malingering) around once every couple of months. It is actually really easy to spot this. I analyse their background by looking at their medical notes. Most severe mental illness, such as psychosis, usually takes months to develop and this happened gradually. So, there's typically some indication of a decline of functioning over time. As opposed to somebody faking mental illness who has suddenly become ill, rather conveniently, at the time they have committed a serious offence. I also utilise collateral evidence; such as observations by prison guards (if the defendant is already on remand) or by psychiatric nurses (if the defendant has been sectioned whilst awaiting trial). I'm always looking for inconsistencies. Finally, people who fake mental illness generally have an agenda; they try too hard to convince me that they are unwell. Whereas somebody who is, for example, generally paranoid tends to conceal it. It takes a lot of effort from me, and some digging around to elicit symptoms of mental illness.

What projects are you currently working on to further inform and educate the public about forensic psychiatry?

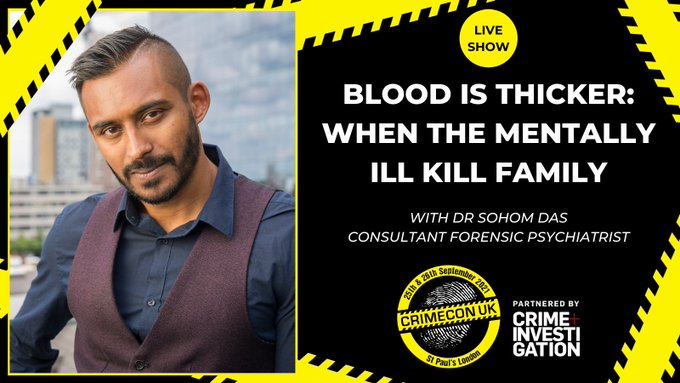

My YouTube channel keeps me very busy! On top of that, I've just finished writing a book which will be published in Spring 2022 by Sphere Publishing called 'In Two Minds'; this is a detailed breakdown of the most fascinating cases throughout my career, intertwined with some personal memoirs. I will also be speaking at CrimeCon UK 25th and 26th September. This is a huge American true crime convention which is coming over to the UK for the first time. I'll be giving a talk about two real life cases I have assessed who have killed family members. I have also been relaying my expert opinion on various documentaries recently. I'm always up for new challenges and new opportunities. I feel I have a duty to inform the public about the world of forensic psychiatry, to quash misconceptions and to hopefully contribute to reducing stigma.

Follow Dr Sohom Das On Social Media

Go Back To The Expert Interviews Page