Interview with Richard E. Cytowic

Want To Study Psychology?

Richard E. Cytowic, MD, MFA, is Professor of Neurology at George Washington University, and best known for bringing synesthesia back to mainstream science. Wednesday Is Indigo Blue won the Montaigne Medal, and he writes The Fallible Mind at Psychology Today.

Q & A

As a leading expert on the phenomenon could you briefly explain what synesthesia is?

Everyone knows the word an–esthesia, which means "no sensation." Syn–esthesia means "joined or coupled sensations," so that my voice, for example, is not only heard but also seen, tasted, or felt as a physical touch.

|

One in 23 people carry the genes for it, and 1 in 90 exhibit some kind of over synesthesia such as colored days of the week or sensing letters and numbers as colored even though they are printed in black ink. |

|

You're renowned for revitalizing scientific interest in synesthesia. Why do you think initial interest in this fascinating topic began to wane?

It was a serious topic for over 200 years until Behaviorism rose in the 1930s. It claimed that externally unverifiable states of mind were outside the realm of science. As a result it relegated memory, language, and emotion beyond the pale, and caused great damage in our efforts to understand the brain. Today we appreciate that 1st–person subjective experience trumps 3rd–person accounts of it every time.

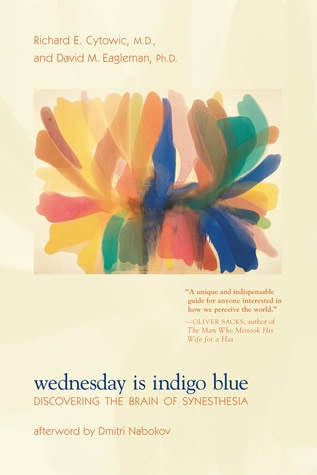

Writing about your award winning book — Wednesday Is Indigo Blue: Discovering the Brain of Synesthesia — the late, great Oliver Sacks said that your work has changed the way we think of the human brain. In what way?

Oliver and I were quite different even though we were two gay neurologists who supported one another’s work. Oliver meant that I’d caused a paradigm shift in how we think the brain is organized, and nothing could be more gratifying for a scientist than to accomplish that. The orthodoxy of five–separate–channels that had dominated neuroscience was out. A new way of thinking was in that appreciated the many ways the senses interact not only in synesthetes but in the rest of us.

People often ask "Why you?" Why did I believe what synesthetic individuals said despite the establishment’s insistence that they were making it up, only wanted attention, were burned–out hippies, or merely remembering associations from coloring books or refrigerator magnets?

The answer has to do with the fact that I’m gay. In 1970 my father’s medical profession said that I was sick, the state of New Jersey said I was a criminal, and the church said I was condemned—and I hadn’t done anything! Their censure was all because of the way I thought. So when the establishment told me that synesthesia couldn’t possibly be real and that it shouldn’t exist, I took to it like catnip.

CLICK HERE for full details of Dr. Cytowic's award winning book.

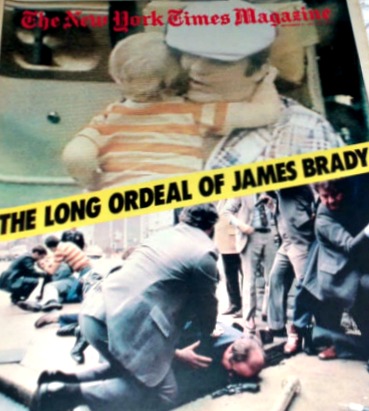

In 1981 you received a Pulitzer nomination for your New York Times magazine cover story about James Brady, the Press Secretary shot in the head during the assassination attempt on President Reagan; in which you stated that the case of Jim Brady "is a medical case that at once illuminates how far the skills of neuroscience have progressed in recent years, and how much we still have to learn." In the years since your story was first published, how much further have the skills of neuroscience progressed and do we still have much to learn?

Each war has brought new advances in how to treat devastating injuries. This is simultaneously good news and bad news. The ultimate question we face is an ethical one: not whether we can save a person because we technically can, but whether we should.

Civilian EMTs often deliver a person to the ER without having given this the slightest consideration. Our ability to intervene rapidly and keep people alive has led to such fraught ethical situations.

Read The Long Ordeal of James Brady

Among your TED-Ed talks is one titled "What Percentage of Your Brain do You Use?" What would you say is the main reason why two thirds of the population and nearly half of science teachers still believe the 10% myth?

It’s such an old story that it’s no wonder people believe it, science teachers included. But once you look at mental work from the viewpoint of "how much energy does this cost?" you’ll think about the time we spend Tweeting, texting, and being online in a whole new light.

If you had to recommend just one of the books that you've read in your capacity as a contributing reviewer at The New York Journal of Books, which book would it be and why?

This is an impossible question because I review everything from science–fiction and novels to biographies and science books. Since you insist, if I had to pick two they would be the translated novel Invisible Love which is gorgeous, and the dystopian Station Eleven.

With the US presidential race in full swing, you've written a couple of intriguing articles on body language for your Psychology Today blog: The Fallible Mind. Why do Ted Cruz’s facial expressions make you feel uneasy?

I never cared about Ted Cruz one way or the other until I watched the first Republican debate. Throughout it I couldn’t stop asking myself what was wrong with his face. It didn’t move the way I expect faces to normally move.

You have to understand that neurologists scrutinize thousands of faces as part of the neurological exam. What I wrote was an explanation of why so many voters found him creepy, and it was based on a straightforward analysis of body language.

Read Dr. Cytowic's Psychology Today article on Ted Cruz

Connect With Dr. Richard E. Cytowic

Recent Articles

-

Psychology Articles by David Webb

Feb 10, 26 06:31 AM

Discover psychology articles by David Webb, featuring science-based insights into why we think, feel, and behave the way we do. -

Music and Memory: How Songs Shape Identity, Emotion, and Life Stories

Feb 10, 26 06:25 AM

How music and memory intertwine to preserve identity, evoke emotion, and anchor life stories. A psychological look at playlists, nostalgia, and the brain. -

Dr. Jody Carrington Interview | Trauma, Connection, and Mental Health

Feb 04, 26 08:18 AM

Interview with Dr. Jody Carrington on trauma integration, loneliness, burnout, and what it really means to feel seen.

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.Go To The Psychology Expert Interviews Page

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.