Proprioception Explained: The Psychology

Behind Your Sixth Sense

Introduction

Often referred to as the "sixth sense," proprioception is the body’s ability to sense its position, movement, and equilibrium without relying on vision. This vital sensory system allows us to walk without watching our feet, type on a keyboard without looking at our hands, and maintain balance in the dark. Despite its fundamental importance to motor control, body awareness, and everyday function, proprioception has historically received less attention than other senses in psychology. This article aims to provide undergraduate psychology students with an in-depth overview of proprioception, its neurological underpinnings, developmental trajectory, clinical relevance, and connections to broader psychological concepts.

Understanding Proprioception

Proprioception, from the Latin proprius (one's own) and capio (to take or grasp), refers to the perception of the body’s internal state—specifically, the sense of limb and body position, movement (kinesthesia), force, and effort. Unlike exteroceptive senses (e.g., vision, touch, and hearing), proprioception is interoceptive and subconscious. It functions continuously, providing the brain with feedback necessary for coordinated movement and posture.

Psychologists and neuroscientists typically distinguish proprioception from related senses like vestibular input (balance and spatial orientation) and tactile feedback. While all contribute to bodily awareness, proprioception is unique in that it informs us about where our limbs are in space without visual cues.

Neurological Basis of Proprioception

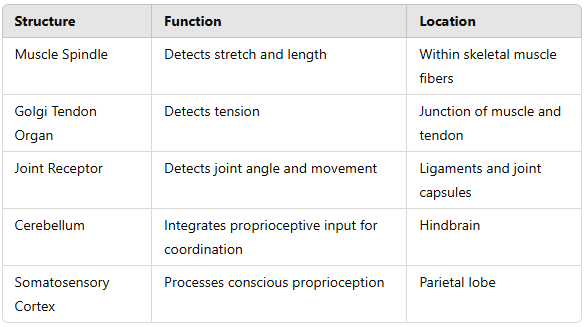

The proprioceptive system relies on specialized mechanoreceptors located throughout the musculoskeletal system:

1. Muscle Spindles: Found within skeletal muscles, these receptors detect changes in muscle length and rate of stretch. They are critical for stretch reflexes and fine motor control (Proske & Gandevia, 2012).

2. Golgi Tendon Organs: Located at the junction between muscle and tendon, these receptors monitor muscle tension and force.

3. Joint Receptors: Present in ligaments and joint capsules, they provide feedback about joint position and movement, particularly at extreme ranges.

4. Cutaneous Receptors: Though primarily involved in touch, certain skin receptors also contribute to proprioception by detecting skin stretch during movement.

These signals travel via the dorsal column-medial lemniscal pathway to the brainstem, then project to the thalamus and ultimately the primary somatosensory cortex, posterior parietal cortex, and cerebellum. The cerebellum, in particular, integrates proprioceptive input to fine-tune motor output and maintain balance.

(Key Proprioceptive Pathways and Structures)

Proprioception in Action

Proprioception is fundamental to virtually every voluntary movement. Whether catching a ball, dancing, or simply scratching your nose, your brain relies on proprioceptive input to plan, adjust, and execute motion without constant visual monitoring. Athletes and musicians develop heightened proprioceptive acuity through practice, allowing them to make rapid, accurate movements.

In daily life, examples of proprioception include:

- Typing on a keyboard without looking.

- Walking across a dark room.

- Balancing on one foot.

- Reaching for an object behind your back.

When proprioception is disrupted—as in certain neurological conditions—people experience difficulty with coordination, clumsiness, and a sense of bodily disconnection.

Development and Plasticity of Proprioception

Proprioception begins to develop in utero and continues through childhood as infants gain control over posture and movement. Studies using motion capture and electromyography (EMG) have shown that even newborns exhibit basic proprioceptive responses (Sampaio et al., 2001).

During childhood, proprioceptive acuity improves with motor learning. Children who engage in physical play, sports, or musical training often develop better proprioceptive abilities. Neuroplasticity plays a critical role here: repeated movement patterns enhance neural connections between proprioceptive receptors and the brain, particularly the cerebellum and sensorimotor cortices (Han et al., 2015).

In older adults, proprioception tends to decline, contributing to balance issues and increased fall risk. This decline is associated with age-related changes in receptor sensitivity and cortical processing (Goble et al., 2009). However, proprioceptive training (e.g., Tai Chi, balance exercises) can mitigate these effects.

Clinical Conditions Involving Proprioceptive Dysfunction

Damage to proprioceptive pathways can lead to significant functional impairments. Some notable conditions include:

1. Sensory Ataxia: Caused by damage to the dorsal columns (e.g., in multiple sclerosis or B12 deficiency), patients lose proprioceptive feedback, resulting in uncoordinated movement and reliance on visual cues.

2. Stroke: Lesions affecting the somatosensory cortex or thalamus can impair proprioception on one side of the body, leading to difficulties with balance and motor planning.

3. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): Many individuals with ASD exhibit altered proprioception, which may contribute to motor delays and sensory integration difficulties (Gidley Larson & Mostofsky, 2008).

4. Peripheral Neuropathy: In conditions like diabetes, damage to peripheral nerves can reduce proprioceptive input from the limbs, increasing fall risk and impairing fine motor skills.

Case studies show that even when other senses are intact, the absence of proprioceptive feedback can severely impact daily functioning. One famous example is that of Ian Waterman, who lost all somatic sensation below the neck due to a rare neuropathy. He was only able to move by using constant visual monitoring and intense concentration (Cole, 1995).

Therapeutic Approaches and Emerging Technologies

Various rehabilitation methods aim to enhance or restore proprioceptive function:

- Physical and Occupational Therapy: Proprioceptive training involves exercises that challenge balance, coordination, and joint position sense (e.g., wobble boards, resistance training).

- Sensorimotor Integration Therapy: Used especially with children with developmental disorders, these therapies combine tactile, vestibular, and proprioceptive input to improve motor planning.

- Prosthetics with Sensory Feedback: Advanced prosthetic limbs now incorporate sensors that provide real-time feedback to the brain, improving control and embodiment (Antfolk et al., 2013).

- Virtual Reality (VR): VR-based rehabilitation allows patients to engage in immersive, goal-directed tasks that challenge proprioception in controlled environments.

Research shows that combining proprioceptive feedback with visual and auditory cues enhances motor learning and cortical reorganization, supporting recovery after injury (Subramanian et al., 2013).

Proprioception and Broader Psychological Concepts

Proprioception has implications far beyond motor control. In psychology, it is linked to:

- Embodiment: The sense of being anchored in one’s physical body. Disruptions in proprioception can alter body schema, affecting how individuals perceive themselves (Tsakiris, 2010).

- Motor Learning: Proprioceptive feedback is essential for refining movements through trial and error, playing a central role in procedural memory.

- Self-Awareness and Interoception: As part of the broader network of body awareness, proprioception contributes to our internal sense of self, especially in relation to movement and agency.

- Cognitive Development: Sensorimotor experiences in infancy, heavily reliant on proprioception, are foundational to later cognitive abilities, according to Piaget’s theory of development.

Conclusion and Future Directions

Proprioception is a critical, though often overlooked, sensory system that underlies our ability to interact with the world. From typing on a laptop to maintaining posture, this "sixth sense" works behind the scenes to coordinate perception and action. As research continues, emerging technologies and neurorehabilitation strategies promise to expand our understanding of proprioception and its plasticity.

Future directions include:

- Investigating the neural basis of proprioception using fMRI and neurostimulation.

- Developing closed-loop prosthetic systems with proprioceptive feedback.

- Exploring proprioceptive deficits in neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders.

- Integrating proprioception into AI and robotics to mimic human-like movement.

By bridging neuroscience and psychology, the study of proprioception offers profound insights into how we move, feel, and experience our embodied selves.

References

Antfolk, C., D'Alonzo, M., Rosén, B., Lundborg, G., Sebelius, F., & Cipriani, C. (2013). Sensory feedback in upper limb prosthetics. Expert Review of Medical Devices, 10(1), 45–54.

Cole, J. (1995). Pride and a Daily Marathon. MIT Press.

Gidley Larson, J. C., & Mostofsky, S. H. (2008). Evidence that the pattern of visuomotor sequence learning is altered in children with autism. Autism Research, 1(3), 148–152.

Goble, D. J., Coxon, J. P., Van Impe, A., Geurts, M., De Vos, J., Wenderoth, N., & Swinnen, S. P. (2009). The neural basis of central proprioceptive processing in older versus younger adults: an fMRI study. Neuroscience, 164(2), 712–722.

Han, J., Anson, J., Waddington, G., & Adams, R. (2015). Proprioceptive performance of bilateral upper and lower limb joints: side-general and site-specific effects. Experimental Brain Research, 233(3), 949–958.

Proske, U., & Gandevia, S. C. (2012). The proprioceptive senses: their roles in signaling body shape, body position and movement, and muscle force. Physiological Reviews, 92(4), 1651–1697.

Sampaio, E., Maris, S., & Bach-y-Rita, P. (2001). Brain plasticity: 'visual' acuity of blind persons via the tongue. Brain Research, 908(2), 204–207.

Subramanian, S. K., Massie, C. L., Malcolm, M. P., & Levin, M. F. (2013). Does provision of extrinsic feedback result in improved motor learning in the upper limb poststroke? A systematic review of the evidence. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair, 24(2), 113–124.

Tsakiris, M. (2010). My body in the brain: A neurocognitive model of body-ownership. Neuropsychologia, 48(3), 703–702.

Note To Psychology Educators

Getting your students to do the 'finger to nose test' is a great way of introducing them to proprioception. This well-known exercise simply requires the test taker to close their eyes and touch the tip of their nose with the tip of their finger. See following video to watch the finger to nose test in action.

Proprioception

Activity

1. Ask your students to name the five major senses i.e. smell, taste, touch, hearing and sight.

2. Get your students to do the finger to nose test.

Reflection question:

Which of your 5 major senses did you use to find the end of your nose with the tip of your finger?

This question should result in lots of head scratching. Most students will immediately rule out sense of smell, taste and hearing and will also discount sense of sight because their eyes were shut during the test. If sense of touch is offered as an answer, tell your students that it can't be sense of touch because they were not actually touching anything at the start of the test.

So, what sense did students use?

It was proprioception, the process by which sense detectors in our muscles and inner ear tell the brain where our body is in space, which in turn allows us to control our limbs without directly looking at them.

For a great primer on proprioception, get your students to watch the following video.

The

Man Who Lost His Body

To show just how incredibly important proprioception is, I highly recommend psychology teachers highlight the case of Ian Waterman, who is among only a handful of people in the world known to have lost the ability to co-ordinate any kind of movement unconsciously. Watch this video to learn more.

Know someone who would be interested in reading

Proprioception Explained: The Psychology Behind Your Sixth Sense

.

Share This Page With Them.

Go From "

Proprioception Explained: The Psychology Behind Your Sixth Sense

" Back To The Home Page