Interview with Gina Perry

Gina Perry is an Australian psychologist (and member of the Australian Psychological Society) and writer. Her feature articles, columns, and essays have been published in The Age and The Australian, and her short fiction has been published in a number of literary magazines, including Meanjin, Westerly, and Island.

Her co-production of the ABC Radio National documentary about the obedience experiments, ‘Beyond the Shock Machine’, won the Silver World Medal for a history documentary in the 2009 New York Festivals radio awards. She teaches in the Master of Publishing and Communications at the University of Melbourne.

Q & A

What was it about psychology that attracted you to the discipline?

I was debating which courses to take when I finished high school and my sister's flatmate who was studying psychology at university was completely taken by it. She made it sound exciting and interesting. The reality was a bit different. I did my psychology degree at LaTrobe University here in Melbourne and at that time the course was very much 'rats and stats' based. Probably because of that, I found social psychology - with its emphasis on human interaction - fascinating

In the course of your research for your critically acclaimed book - Behind the Shock Machine The Untold Story of the Notorious Milgram Psychology Experiments; what finding or discovery stayed with you the most?

It's hard to pick one thing because over the course of four years of research so many things jumped out at me so I'll start with one finding that set off a series of others.

The first was the realization that many people including myself came to conclusions about human nature based on Milgram's finding that 65% of his subjects obeyed orders from an authority figure to inflict pain on someone else. And yet the sample that we base that conclusion on is a group of just 26 people. This data wasn't new, it wasn't something I discovered in the archives, it was published in Milgram's articles and in his 1974 book. But it really made me sit up and question why we have so easily and uncritically made the leap from such a small group of people to the world at large.

That was a turning point for me because I saw that I would have to question all my assumptions about the obedience experiments. That led me to the archives at Yale, to his unpublished writings and original data, including audio recordings of the experiments. It also led me to interview surviving subjects, Milgram's staff and their relatives and in the course of that I realized how much about the people involved had been excluded from the story. During that time I heard of a large scale repeat of Milgram's research at my own university. Meeting and interviewing people who took part in that experiment, as well as some who took part at Yale, made me think about the experiment in entirely new ways. If we really want to understand the obedience research, we have to go back and look at what the subjects involved in the study were thinking and feeling. That's what has been missing for so long. We're given statistics and descriptions and the occasional anecdote about subject behavior but the perspective of the participants is critical to the story.

In the process of this archival research and interviewing people I found a number of troubling disparities between what we've come to believe about the research, how it was conducted and the meaning of the results.

What did you mean when you said "Milgram's obedience experiments are as misunderstood as they are famous."

For starters, there's the sweeping generalisations made about humankind on the basis of the behavior of 26 people in one variation out of a total of 24 variations that I mentioned earlier. When I looked at all of the 24 variations of the experiment, I found that in over half of them 60% of people had disobeyed.

One of the other things most people don't realize is how much debate there still is among scholars about the meaning and value of the obedience research. Textbook accounts of the research tend to locate controversy about Milgram's research in terms of the ethical debates that ensued about his treatment of subjects. In fact debates about the methodological problems with the research, and the weakness of Milgram's explanation and theory, continue today.

For example, a number of scholars have questioned how believable the experiment was to the subjects. My research in the archives uncovered many subjects expressing skepticism about the experimental set up. Milgram dismissed subjects' doubts about the believability of the experiment as a form of denial, a way of rationalizing behavior they were ashamed of by saying they'd seen through the experiment all along. Papers at Yale indicate that many subjects expressed skepticism both during and immediately after the experiment - before it's purpose had been explained. And their feedback was very specific. For example many commented that it was unbelievable that a man with a heart condition would agree to be in an experiment where he would be given electric shocks. Some commented that the learner's voice sounded like it was coming through speakers in the ceiling, suggesting it was a recording. Others queried why the experimenter was watching them and not the learner. Many offered to switch places with the learner, and on the tapes you can hear many of them stressing the right answer when they were reading the potential answers to the learner, that is they tried to cheat on the memory test by helping the learner pick the right answer. I also found that the experimenter urged and pressured people to continue way beyond the four standard times we've been told. When you listen to the audio recordings of the experiment it sounds much more like bullying and coercion by the experimenter than slavish 'obedience to authority.' None of this made its way into official accounts of the research.

You'll often read about or hear people referring to 'replications' of Milgram's experiments over the past 50 years and in countries around the world. Again, once you examine this is a bit more detail you find that people use 'replication' to describe experiments that bear little resemblance to the original, that use a diverse range of different subjects and which yield hugely varying results.

For a detailed account of Gina Perry's research into the Milgram experiments, CLICK HERE to listen an interview she did for ABC radio in Australia.

You recently re-examined Muzafer Sherif's classic Robbers Cave Experiment on intergroup relations and refer to Sherif's less well known, 'failed' versions of the experiment. Could you tell us something about these 'failed' versions?

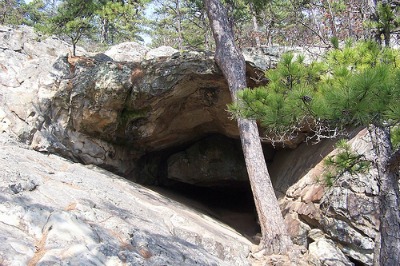

(Entrance to Robbers Cave. Image by Stephen Conn via flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

Sherif conducted three studies of which the Robbers Cave in 1954 was the most famous. The other two were held in 1949 and 1953. Sherif makes little mention of the 1953 study, regarding it as a failure because the two groups of boys he hoped to pit against each other refused to be drawn into conflict. He abandoned the study, and with his colleagues planned the third and final effort which was Robbers Cave which delivered the results he was hoping for. These earlier versions of the study have a lot to tell us about the psychology of social psychological research at that time, as well as offering an alternative view of the more famous study’s conclusions.

For more information on Gina Perry's research into the Robbers Cave Experiment, CLICK HERE to listen to an excellent radio broadcast on the topic which she produced for the Hindsight program on ABC radio in Australia.

Are there any other psychology classics which you would like to investigate?

Yes, I would love to research Festinger et al's 'When Prophecy Fails Study'. The idea of a bunch of psychologists infiltrating a cult is fascinating.

Why do you think certain psychology experiments and studies continue to fascinate, engage and resonate with people decades after they were originally published?

I think it's partly because they seem to explain something we find inexplicable. For example, Milgram's obedience studies are often described as explaining some aspect of the Holocaust. Secondly, they are powerful and dramatic stories. In Milgram's case you have these seemingly ordinary people, invited into a university laboratory, who behave in ways we would normally think of as inhumane and cruel. These studies are powerful too because they are repeated so often. In the case of Milgram's research, in the process of being repeated, the story has been simplified, the complexities or ambiguities are edited out or are lost in translation.

Do you have any best practice tips or advice for psychology students when conducting interviews?

It depends what the purpose of the interview is but if it's to gather people's memories, thoughts and feelings about an event then these are my tips.

- Do as much research as you can beforehand. That way you can use your interview time to fill gaps and double check what you understand.

- Make a list of what you want to ask. But don't stick to it slavishly. Sometimes you need to adapt (or even throw away) your questions according to what answers people give you.

- Do the interview somewhere quiet where you won't be interrupted. Think about somewhere your interviewee will feel comfortable.

- Turn off your phone.

- Listen closely. This is a skill. It means paying much closer attention than we usually do in everyday conversation.

- Stay quiet between questions. Your interviewee should be doing most of the talking.

- Don't jump in too soon to ask the next question. People will sometimes fill a quiet spot with more information.

- Don't be afraid to say if you don't understand something. Ask people to elaborate or explain. People appreciate you wanting to get things right.

- Take good notes and record everything.

- Expect to get the best quotes/most interesting stories as you are packing up to leave.

- Always follow up someone you've interviewed, thank them and update them on the progress of your project.

Connect With Gina Perry

CLICK HERE to visit Gina Perry's website.

CLICK HERE to connect with Gina Perry on Twitter.

CLICK HERE to connect with Gina Perry on Facebook

Recent Articles

-

Continuing Bonds: The Psychology of Staying Connected After Loss

Mar 06, 26 08:59 AM

Continuing bonds research shows staying connected to loved ones after death is healthy, not pathological. Explore grief psychology, attachment theory, and cultural mourning. -

Tourettes: Understanding Tourette Syndrome Beyond Stereotypes

Feb 23, 26 06:01 AM

Learn what tourettes really is, why swearing is a myth for most, and how education reduces stigma around Tourette syndrome. -

Psychological Impact of Catastrophic Injury & Recovery

Feb 17, 26 02:26 AM

Explore the psychological impact of catastrophic injury, including trauma, identity shifts, resilience, and long-term mental health recovery.

Go To The Psychology Expert Interviews Page