Interview With Elizabeth Loftus

Elizabeth Loftus is Distinguished Professor at the University of California - Irvine. She holds faculty positions in the Department of Psychological Science; the Department of Criminology, Law & Society, and the School of Law. She received her Ph.D. in Psychology from Stanford University. Since then, she has published over 20 books and over 600 scientific articles. Loftus's research has focused on the malleability of human memory. This extensive body of research has shown us how, why, and when our memories can be changed by new experiences that we have after some key information is stored in memory. Those new experiences can contaminate memory, leading to transformations, alterations, and distortions of what was previously experienced.

She has been recognized for her research with eight honorary doctorates and election to numerous prestigious societies, including the National Academy of Sciences, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the American Philosophical Society. She is past president of the Association for Psychological Science, the Western Psychological Association, and the American Psychology-Law Society.

Loftus has won more than a dozen major awards for her scientific work. These include the two top awards from the Association for Psychological Science: the James McKeen Cattell Fellow ("for a career of significant intellectual contributions to the science of psychology in the area of applied psychological research") and the William James Fellow Award (for "ingeniously and rigorously designed research studies…that yielded clear objective evidence on difficult and controversial questions"). The list also includes the Distinguished Scientific Award for Applications of Psychology from the American Psychological Association and the Gold Medal Award for Lifetime Achievement in Science from the American Psychological Foundation (for "extraordinary contributions to our understanding of memory during the past 40 years that are remarkable for their creativity and impact"). She won the Grawemeyer Prize in Psychology (to honor ideas of "great significance and impact"), which came with a $200,000 gift. More recently: 1) the John Maddox Prize from Nature Magazine (for "courage in promoting science and facing hostility in doing so"), 2) the Ulysses Medal from University College, Dublin, Ireland ("the highest honor bestowed by UCD"), 3) the Suppes Prize from the American Philosophical Society ("in recognition of her demonstrations that memories are generally altered, false memories can be implanted, and the changes in law and therapy this knowledge has caused"), and 4) the Lifetime Career Award from the International Union of Psychological Science (for "distinguished and enduring lifetime contributions to advancing knowledge in psychology").

Loftus's memory research has led to her being called as an expert witness or consultant in hundreds of cases. Some of the more well-known cases include the McMartin Preschool Molestation case, the Hillside Strangler, the Abscam cases, the trial of the officers accused in the Rodney King beating, the Menendez brothers, the Bosnian War trials in The Hague, the Oklahoma Bombing case, and litigation involving Michael Jackson, Martha Stewart, Scooter Libby, Oliver North, Bill Cosby, Harvey Weinstein, and the Duke University Lacrosse players.

Perhaps one of the most unusual signs of recognition of the impact of Loftus's research came in a study published by the Review of General Psychology. The study identified the 100 most eminent psychologists of the 20th century, and not surprisingly, Freud, Skinner, and Piaget are at the top of that list. Loftus was #58, and the top-ranked woman.

In your groundbreaking research on the misinformation effect, you’ve demonstrated how subtle changes in phrasing can distort memory. Looking back, what was the most surprising or unexpected finding that emerged from your experiments, and how did it shape the trajectory of your subsequent research?

I'm not sure that I would call this necessarily a surprising effect, but when I first started wanting to do these studies of eyewitness memory and I wanted to study specifically the questioning process and how the wording of questions would affect the answer that somebody gave, I designed some very simple studies, where, for example, we showed people an accident—a simulated accident—and our witnesses were asked a question about the speed of the vehicles. Depending on how we worded the question, we got different answers. So, people who were asked, 'How fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?' gave a higher estimate than people who were asked, 'How fast were the cars going when they hit each other?'

So now we had demonstrated that just changing a word or two in the question could affect the answer somebody gave. But what I think was a little bit more—I don't know if you'd call it revolutionary or at least theory-changing in my world—was when we did another experiment where we came back to people a week later and said, 'Did you see any broken glass?' People were more likely to tell us they saw broken glass, which did not exist, if we had used the word 'smashed' a week before, compared to those other witnesses who were questioned with the verb 'hit.'

This showed not just that the wording of a question could affect the answer, but it could have a long-range effect. It could affect the answer to a totally different question that you put to somebody much later. And we would argue—and I think would find support for the idea—that these early questions were actually contaminating memory. And, of course, that led to the idea that the questioning process is not the only way to contaminate memory. You can contaminate it in all sorts of ways, and that led to the idea of the misinformation effect. Anything you do that supplies some sort of misinformation to a witness can have this kind of contaminating effect.

The 'lost-in-the-mall' experiment is one of your most iconic studies. For those who may be unfamiliar with it, could you briefly explain the nature of the experiment along with its key findings?

The idea for the study itself grew out of a court case that I was involved in as an expert witness. It was a murder case where a woman accused her father of murdering her little best friend 20 years earlier, and I suspected that she might have a false memory of witnessing this experience. But if she did, then she had created a really rich false memory. She didn't just decide there was broken glass at an accident when there wasn’t, but she would have had to create an entire false memory.

So, I wanted to study that process—how can you plant a seed and watch it grow into a whole false memory? The first study that we did was to plant the seed of suggestion that, when you were five or six years old, you were lost in a shopping mall, frightened and crying, and ultimately rescued by an elderly person and reunited with your family. With as few as three suggestive interviews, we got about a quarter of ordinary adults to fall sway to this suggestion and start to believe all or part of this made-up story about being lost in the mall.

I should also mention that recently, a group of Irish investigators did a registered replication of the 'lost in the mall' study, and they found an even larger percentage of their sample falling for the suggestion—I think it was about 35 percent. But basically, they replicated the basic finding that you could do this with ordinary people. They went a bit further in showing that if you show these memory reports to other people, like jurors listening to a memory report, ordinary people tend to believe it’s authentic. So, these reports sound very believable when other people hear them, even though they are constructed through the suggestive process.

Click Here to read the accepted manuscript version of the replication of the 'lost in the mall' study.

Your research has significantly impacted legal practices, particularly in the evaluation of eyewitness testimony. If you were to propose one additional reform to the justice system based on your findings, what would it be, and why?

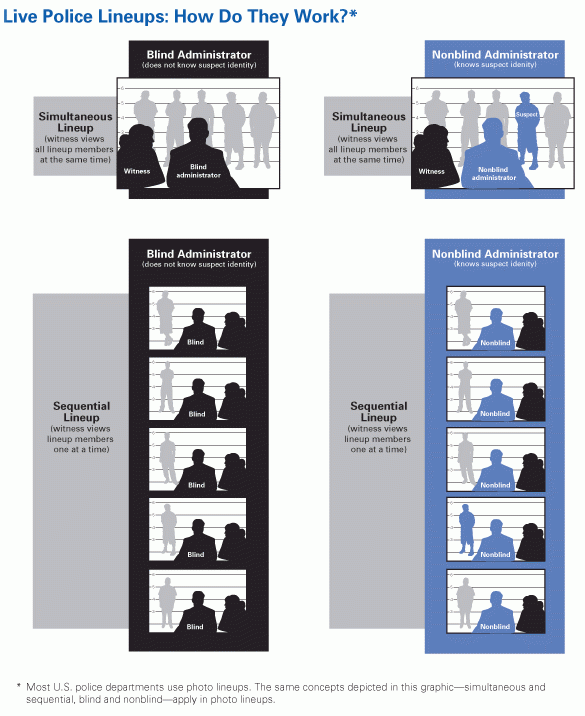

Many psychologists have done research on eyewitness memory—memory as it applies in legal cases—and their work has suggested a number of reforms that I think are widely accepted in the psychological community but maybe only partially accepted in the world of law enforcement. For example, blind testing: if you're conducting a lineup and trying to get a witness to identify a perpetrator of a crime, the person who conducts the lineup should be somebody who doesn't know who the suspect is. That is probably one of the most important reforms that's been suggested by the work of many who work in this space.

The reason why you want this kind of blind testing—where somebody conducting the lineup doesn't know who the suspect is—is because you don't want that person conducting the lineup to be able to, even unwittingly, cue the witness as to who the suspect is or what answer the interviewer is hoping to get.

A second reason for blind testing is that often witnesses will say, 'Okay, did I pick the right person? Did I give the right answer?' You don't want the interviewer giving this kind of feedback, saying, 'Good job, yes you did, that's our suspect,' because that kind of feedback is going to artificially enhance the confidence of the witness. It can affect their memory, make them more confident, make them more certain about other details, and make them a more compelling witness—even if they're wrong.

This graphic illustrates the differences in live police lineup presentation. In a simultaneous lineup, the witness views all lineup members at the same time. In a sequential lineup, the witness examines lineup members one at a time. In either model, the lineup administrator can be blind, meaning he or she does not know the identity of the suspect, or nonblind, meaning the administrator knows the identity of the suspect. Most U.S. police departments use photo lineups. The same concepts depicted in this graphic—simultaneous and sequential, blind and nonblind—apply in photo lineups. (Graphic and description courtesy of National Institute of Justice).

The repressed memory controversy has been an ongoing debate within the field of psychology and mental health for decades. What would you say is the biggest misconception about repressed memory?

There is a belief among some practitioners that you can have a huge collection of horrific traumas—for example, being raped from the ages of 5 to 15—which you can banish into the unconscious, so that they can be walled off from the rest of mental life, and you can have absolutely no awareness that this happened to you until a long time later when you go into therapy and unearth these allegedly repressed memories and it's my position that there really is no credible scientific support for the idea that memory works like this—that we do wall things off and they're protected in some pristine form. There's no credible evidence that unearthing these buried trauma memories actually helps people, and in fact, these practices have led to accusations against innocent people and convictions of people for crimes they didn’t commit.

You can learn more about the repressed memory debate by watching the following video. This brilliant interview of Elizabeth Loftus by Dr. Carol Tavris touches on the intense scrutiny and backlash Professor Loftus faced from proponents of repressed memory therapy. The interview also explores Professor Loftus's career trajectory, her impactful research on eyewitness testimony and false memories, her involvement in high-profile legal cases, and ethical considerations surrounding memory manipulation.

With the rise of AI and deepfake technology, the potential for fabricated visual and audio evidence has grown exponentially. In relation to these advancements influencing memory and distorting the truth, how worried should we be?

I think we should be very worried. For at least a decade now, psychologists have done experiments showing that doctored photographs can contaminate people's memories. In one famous study, if you create a doctored photograph of someone who, as a child, was going up with their parent in a hot air balloon ride, just looking at that doctored photograph is enough to get people to think that this actually happened to them. So how much more vivid and how much more compelling are the AI-generated fake videos that can be constructed? These videos can show people doing all kinds of different things and can potentially contaminate people's memories of what they experienced. And as the technology gets easier and easier, and masses of our fellow citizens are able to use it, we could get people all around us trying to contaminate our memories—and succeeding at doing so.

In some of your research, you’ve explored the positive applications of memory manipulation, such as encouraging healthier behaviors. What do you think are the most promising areas where memory research could be applied for societal benefit?

At some point, I got very interested in the repercussions of developing a false memory. My collaborators and I decided to explore this by trying to plant false memories that, when you were a child, you got sick eating particular foods—like eggs, pickles, or strawberry ice cream. What we found is that when we planted a false memory that you got sick eating one of these foods, people were not so interested in eating those foods. And when you put foods in front of people and gave them an opportunity to choose what they wanted to eat, they were less likely to eat a food after they had developed a false belief or memory about getting sick on that food.

Then we showed you could plant a false positive memory about a healthy food, and people were more interested in eating those foods. I remember that The New York Times voted this line of research—which they called the 'false memory diet'—one of the most promising scientific discoveries of that year. That was a big surprise and a big honor for me.

Potentially, I think we could use these techniques to manipulate people's memories about certain foods to guide them into eating foods that are healthier for them—maybe even make a dent in the obesity problem in our society. I think this might be a good thing, even though it's a little creepy for some people to think about this kind of methodology because it involves mind manipulation. But my response to that, of course, is, you know, if you had a teenager who was very obese and in jeopardy of getting diabetes, heart problems, a shortened lifespan, and all the things that go with that, maybe you might be a little bit more in favor of some false memory diets.

Despite decades of research, many people still trust their memories implicitly. What strategies do you believe are most effective in raising public awareness about the malleability of memory?

I have long been interested in trying to communicate these scientific findings to a broader audience. I want to speak to more than, you know, the 150 students who used to take my cognitive psychology class, or the 35 students who now take my eyewitness memory class, or the 12 people who sit on a jury where I'm testifying. And so, I have tried to be responsive to journalists who are doing magazine articles or podcasts or other forms of social media, and that's kind of been my personal strategy. But I'd love to think further about what else we can do.

I love the idea that some of our professional organizations are teaming up with Hollywood to try to educate producers of Hollywood projects, films, documentaries, and other projects to further reach a larger audience with important scientific findings about psychology in general. And for me, the malleability of memory. And so, I'm hopeful that that could happen. You know, I've been participating in a documentary recently. I'm working on a science memoir right now, and I hope some of these efforts might make a difference.

Your work has inspired countless researchers and practitioners in psychology and law. Who or what inspired you to pursue the study of memory in the first place?

Well, that goes way back to graduate school. So, when I was in graduate school, I was studying mathematical psychology, and I was working with some very prominent, important faculty on projects having to do with computer-assisted instruction in mathematics and other topics. I was one little part of a great, big enterprise. I was not as enthralled with that work as I wanted to be.

There was a faculty member at Stanford, where I was in grad school, who was studying memory, and he invited me to join his project. That was the first time I began to do a study with this professor on memory. I realized that I could be an experimental psychologist and help design a study of memory, run the subjects, analyze the data, and write up the article for publication and so on. So, that was the beginning of my interest in memory.

Then, after getting my PhD and wanting to do work that had more obvious practical applicability—because the memory work I had done up to that point was more theoretical and not as practical—that's when I turned my attention to eyewitness memory. Memory for victims and witnesses to crimes, accidents, and legally relevant events. So, that's kind of how all that happened quite a long time ago.

If you were to begin your career in memory research today, what would be your first area of focus, and what do you think remains the biggest unanswered question in the field?

I think there's still lots of room for more discoveries about the malleability of memory. For example, I use behavioral techniques to manipulate memory, but maybe, in combination with psychopharmaceutical ingredients, you might find it sometimes easier to create memories or distort people's memories. There's just a whole lot more to learn.

I've been collaborating with investigators at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology on how large language models, if they're doing the interviewing of people, can create more false memories, which we are finding in one of the studies. There's just so much more to do and learn—integrating modern technology with the basic phenomenon of the misinformation effect.

Learn More

For anybody interested in taking a deep dive into the fascinating world of memory and its fallibility, make sure you visit Professor Loftus's faculty webpage where you can download an amazing collection of her published research for free. And don't forget to watch Professor Loftus's TED talk which has been viewed over six and a half million times.

Note To Psychology Students

If you're searching for an engaging and impactful topic for a research project or final year dissertation, consider exploring the malleability of human memory. This area, championed by the groundbreaking work of Professor Elizabeth Loftus, offers endless possibilities for meaningful inquiry. Here’s why this is such a fascinating and rich topic for study:

Uncharted Territory:

As Professor Loftus herself stated in this interview, "There's just so much more to do and learn." Despite years of groundbreaking research, many unanswered questions remain about how memories are formed, altered, and fabricated. Advances in technology, such as AI and psychopharmaceuticals, continue to open new doors for exploration.

A Strong Foundation for Inquiry:

You’ll have the benefit of a robust, decades-long body of research to draw from when conducting your literature review. Professor Loftus’s pioneering studies, including those on the misinformation effect and false memories, offer a solid foundation for generating research questions or formulating experimental hypotheses.

Opportunities for Replication Studies:

Given the foundational nature of much of Professor Loftus's work, replication studies can be an excellent starting point. Whether it's revisiting the iconic "lost-in-the-mall" experiment or exploring the nuances of the misinformation effect, replication allows you to validate existing findings while potentially uncovering new dimensions of the phenomenon.

Interdisciplinary Relevance:

Memory research intersects with psychology, law, neuroscience, and modern technology. This interdisciplinary appeal not only broadens the scope of your inquiry but also enhances the real-world relevance of your work, particularly in fields like criminal justice, education, and mental health.

Practical and Ethical Implications:

The study of memory is not just theoretical—it has profound implications for understanding eyewitness testimony, preventing wrongful convictions, and improving therapeutic practices. Investigating such topics allows you to contribute to both science and society.

By choosing to focus on the malleability of memory, you’re stepping into a dynamic and impactful area of psychology with the potential to make meaningful contributions. Whether you’re drawn to the theoretical aspects, the ethical debates, or the practical applications, this is a topic with endless possibilities for discovery.

Go To The Expert Interviews Page

Go From The Interview With Professor Elizabeth Loftus., Back To The Home Page