Psychology Classics On Amazon

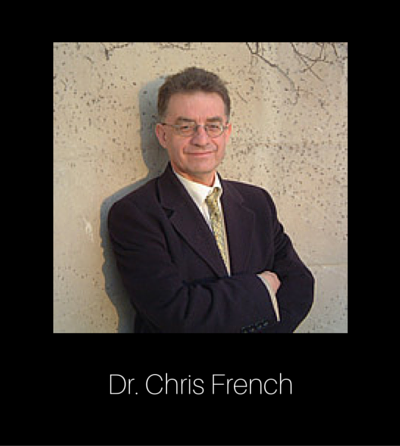

Interview with Dr. Chris French

Chris French, Ph.D., is professor of psychology and head of the Anomalistic Psychology Research Unit at Goldsmiths, University of London. He is renowned for his research on the psychology of paranormal belief; particularly his work on non-paranormal accounts of ostensibly paranormal experiences (ESP, PK, psychic readings, psychic healing, alternative and complementary medicine, out-of-body and near-death experiences, astrology and other divinatory techniques, reincarnation, UFOs and alien abduction, ghosts and poltergeists, crystal power and dowsing etc).

A special advisor and former Editor-in-Chief of The Skeptic Magazine, the UK's foremost and longest-running skeptical magazine, Professor French is regularly called upon in the media to offer a psychological perspective on various paranormal claims. He is also a columnist for the Guardian’s online science pages.

Q & A

What led you to pursue an academic interest in the psychology of paranormal beliefs?

Paranormal claims have always fascinated me. Up until my mid-twenties, in fact, I believed in many paranormal phenomena. It was reading one particular book in the early 1980s, Parapsychology: Science or Magic? by James Alcock, that opened my eyes to the fact that plausible non-paranormal explanations for ostensibly paranormal experiences existed, many of which were supported by good empirical evidence. I took my interest further by reading books by the likes of Ray Hyman, James Randi, Martin Gardner and others. I subscribed to the American Skeptical Inquirer magazine and to the British Skeptic magazine (then known as the British and Irish Skeptic).

Although I was fascinated by the sceptical approach to the paranormal and other pseudosciences, for a long time my interest was little more than a personal hobby. I gave occasional talks and lectures on the subject but was not actively involved in doing research related to my interest. Back then, anomalistic psychology was not seen by many as being a properly 'respectable' area for serious research - after all, they talked about such topics on daytime TV!

With the benefit of hindsight, one can see that attitudes were slowly beginning to change, thanks in the UK to the pioneering efforts of people like Susan Blackmore, Robert Morris, and Richard Wiseman, but it was not until 1992 that I published my first academic papers in this area. Even then, I felt my interest in the 'weird stuff' was tolerated but not encouraged and I made sure I was publishing papers in more traditional areas of psychological research as well.

I am not quite sure exactly when I decided to focus my research solely upon anomalistic psychology but clearly that did happen at some point. I began teaching an optional module on anomalistic psychology as part of Goldsmiths' BSc (Hons) programme back in 1995 and founded the Anomalistic Psychology Research Unit (APRU) in the year 2000. One reason for doing the latter was to raise the academic profile of anomalistic psychology and, along with that, its academic respectability. I like to think we've been pretty successful in achieving those aims. These days, almost all of my research and other academic activities are within the area of anomalistic psychology.

Why are paranormal beliefs among the general public so pervasive?

There are many factors that play a role in the popularity of paranormal beliefs but I believe that one of the most important is our evolutionary history. Various cognitive biases appear to be associated with belief in the paranormal such as our tendencies to detect meaningful patterns in randomness, to perceive illusory cause-and-effect relationships, and to automatically assume that everything that happens happens because someone or something - some sentient external agent - wanted it to happen. All of these tendencies occur because we are applying cognitive tendencies that, during our long evolutionary history, would have helped to keep us alive by alerting us to potential threats in our environments. That way, we'd pass on our genes to the next generation. But when these same tendencies are applied inappropriately they can result in belief in paranormal forces, worthless alternative therapies, and ghosts and other spiritual beings.

Additionally, there is no doubt that people have weird experiences, such as out-of-body experiences, near-death experiences, and sleep paralysis, that appear on the surface to offer support for certain paranormal belief systems. Then there is the role of wider cultural belief systems, particularly religions, which also promote paranormal beliefs in various ways. The single most pervasive cognitive bias is that of confirmation bias. We all find it easy to believe stuff that we'd like to be true anyway. When it comes to, say, belief in life-after-death, the evidence to convince us that it is real does not have to be strong for us to accept it.

Of all the beliefs and experiences people label as paranormal, which are the most common?

There will, of course, be variations across cultures, both historically and geographically but in modern Western societies it is typically found that around 30-50% of the adult population will endorse beliefs in a wide range of paranormal phenomena including life-after-death, ghosts, communicating with the dead, telepathy, and precognitive dreams. A smaller but still substantial proportion claim to have had direct personal experience each of these phenomena.

Have you ever investigated a 'paranormal' experience that couldn't be explained in terms of known or knowable psychological and physical factors?

I am not claiming that I could provide definitive non-paranormal explanations for each and every paranormal claim that has ever been made - and neither should anybody else. Typically, one is not investigating the experience or event itself but someone's report of it. Even though the claimant may be totally sincere in making the claim, we know beyond doubt that memory can be notoriously unreliable. And of course, deliberate hoaxes do occasionally occur. Therefore, anecdotal claims would never be enough to convince me that a paranormal phenomenon had taken place.

Results from well controlled experiments potentially could convince me that paranormal forces really do exist. But, to date, parapsychologists have failed to come up with a single paranormal phenomenon that can be reliably replicated. To me, that speaks volumes.

I typically find that, with very few exceptions, paranormal claims become less and less convincing the more one digs down into the details of the claim. But an important part of scepticism is to always be open to the possibility that new evidence may come along which proves one wrong. For that reason, we will continue to test paranormal claims as fairly as we can despite the fact that none of our previous tests has ever produced compelling evidence to support a paranormal claim.

In your column for the Guardian's online science pages you published an article concerning the ideomotor effect. Could you tell us more about this particular psychological phenomenon?

A number of paranormal and related claims are plausibly explained in terms of the ideomotor effect, that is, non-conscious muscular movements. In all cases of the ideomotor effect, non-conscious muscular movements are caused by a belief or suggestion. Paranormal phenomena that can be explained by this phenomenon include:

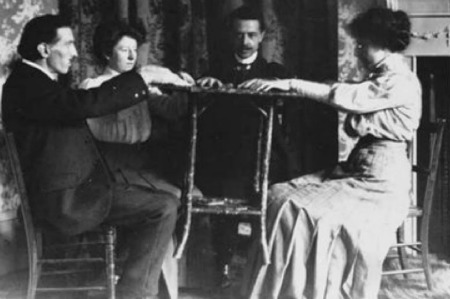

- Table-tilting: This was a Victorian craze involving sitters attempting to communicate with spirits by placing their hands upon small round wooden tables. The table's movements were said to be caused by spirits but physicist Michael Faraday proved conclusively that the sitters were unwittingly causing the movements themselves.

- Ouija board: Another alleged tool for communicating with spirits, in this case the sitters place their fingers on a planchette (or an upturned wine glass) which moves around in response to questions indicating letters, numbers, and the words "yes" and "no" positioned around the board.

- Dowsing: A technique used for a variety of purposes including finding water in dry areas, determining the sex of unborn children, and communicating with spirits. A number of different methods exist for dowsing using such devices as L-shaped rods, Y-shaped branches, or pendulums, but in all cases a tiny movement on the part of the dowser is converted into a large movement of the system in use. The movements of the system are said to provide the requested information. Testing under double-blind conditions has repeatedly shown that this is not the case.

What would you say have been the most significant developments within the discipline since you established the Anomalistic Psychology Research Unit in the year 2000?

I think it's fair to say that there have not been any specific dramatic breakthroughs within the field but there has been a steady accumulation of knowledge as reflected, year on year, by the increasing number published papers, books, conferences, and so on.

There has also been an increase in the amount of teaching of anomalistic psychology topics at all levels, not least because it provides an engaging vehicle for the fostering of critical thinking skills. So I guess what I find most gratifying is the general acceptance that the topics covered within anomalistic psychology are now considered by almost everyone to be worthy of proper scientific study.

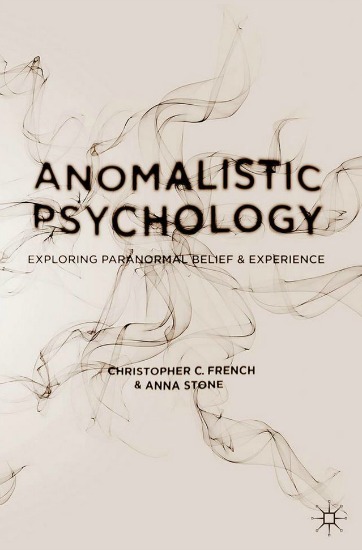

Could you tell us about the book you co-authored with Anna Stone, Anomalistic Psychology: Exploring Paranormal Belief and Experience?

That book is an attempt to give a state-of-the-art snapshot of anomalistic psychology by considering each of the major sub-disciplines of psychology in terms of what insights they can provide in helping us to understand paranormal beliefs and experiences. Cognitive psychologists have described many biases that have relevance in explaining why people sometimes misinterpret experiences as involving paranormal forces when in fact they do not.

Social psychologists describe the mechanisms by which beliefs are transmitted between individuals. Developmental psychologists offer insights into children's understanding of magic and superstitious beliefs. Neuroscience can explain many ostensibly paranormal experiences in terms of what is happening within the brain. I think ours was the first book to take this approach and I think it emphasises nicely the need to consider many different aspects of the rich and multifaceted bizarre experiences that constitute ostensibly paranormal phenomena.

What advice would you give to somebody who is interested in becoming an anomalistic psychologist?

It is essential to first get a good grounding in psychology as a whole, including research methods and statistics, before specialising in anomalistic psychology. That is best done by studying psychology at undergraduate level, probably followed by an MSc in research methods. At both undergraduate and Masters level, choose project topics within anomalistic psychology. The next step would be to apply for a PhD investigating your chosen topic from within the field. After that, get yourself an academic job where you can carry out research into whatever topics interest you - provided you are doing high quality research of a publishable standard. That makes it all sound very easy and straightforward which it isn't, of course!

And do bear in mind that there will always be a much higher demand for lecturers in the more traditional sub-disciplines of psychology as opposed to niche areas like anomalistic psychology. But at the end of the day, researchers often end up working in their chosen areas simply because that is where their real interests lie, no matter what barriers are put in front of them - and that certainly applies to my own research career.

What research projects are you currently working on?

As always, we have a number of different projects at different stages of development but the three topic areas that seem to occupy the majority of our research effort at the moment are the psychology of belief in conspiracies, false memories, and sleep paralysis. In addition to the research itself, we put a lot of effort into public engagement by way of cooperation with the media, organising and contributing to conferences and talks series, and sci-art collaborations. There are no signs of the public's fascination with anomalistic psychology waning in the foreseeable future.

Brilliant demonstration of auditory top-down processing by Professor Chris French

Connect With Dr. Chris French

Recent Articles

-

All About Psychology

Apr 22, 25 02:37 PM

A psychology website designed to help anybody looking for detailed information and resources. -

Sponsor a Psychology Website with Over a Million Yearly Visitors

Apr 22, 25 10:07 AM

Showcase your brand to a huge, engaged audience. Discover how to sponsor a psychology website trusted by over a million visitors a year. -

Billy Milligan Case Study: Psychology, Crime, and the Split Mind

Apr 18, 25 09:10 AM

Was Billy Milligan a fractured victim—or a manipulative genius? This Billy Milligan case study explores the psychology behind one of history’s most controversial trials.

Know someone who would love to read this interview with Professor Chris French? Share this page with them.

Please help support this website by visiting the All About Psychology Amazon Store to check out an awesome collection of psychology books, gifts and T-shirts.

Go To The Psychology Expert Interviews Page

Go From Chris French Q & A Back To The Home Page

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.