Psychology Classics On Amazon

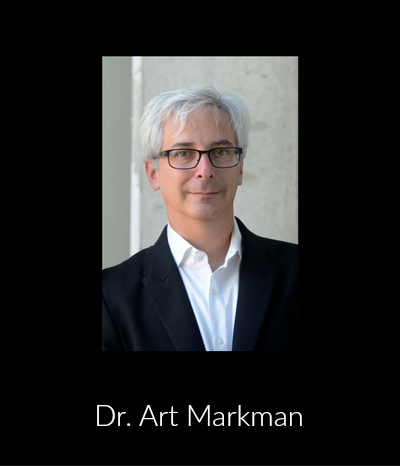

Interview with Dr. Art Markman

Want To Study Psychology?

Art Markman, Ph.D., is the Annabel Irion Worsham Centennial Professor of Psychology and Marketing at the University of Texas at Austin. A renowned cognitive scientist and author, Dr. Markman has published over 150 scholarly works on topics in higher-level thinking including the effects of motivation on learning and performance, analogical reasoning, categorization, decision making, and creativity.

A much sought-after expert within the workplace and broadcast media, Dr. Markman consults for companies interested in using Cognitive Science in their businesses and is on the scientific advisory boards for the Dr. Phil Show and the Dr. Oz Show.

Q & A

What led you to pursue an interest in cognitive science?

I went to college thinking I would major in economics of physics. After taking classes in each, though, I realized they weren't for me. When I sat down with an advisor in my Sophomore year in college, I told her I had no idea what to major in. She asked me what classes I liked. I said that I liked my computer science classes, but didn't want to be a CS major, my psychology classes, but didn't want to be a psych major, a linguistics class I took, but I didn't want to be a linguistics major, and the anthropology classes I took, but I didn't want to be an anthro major. She told me all of those classes would satisfy requirements in the cognitive science major, so perhaps I was a cognitive scientist. After looking into it more, I realized I was.

I ultimately got my PhD in psychology, because in the 1980s when I was in college, computers were slow and had too little access to data for me to feel like I would make progress working in artificial intelligence. But, I ended up working in Dedre Gentner's lab as a grad student. Her husband Ken Forbus is in computer science. So, in essence, I was doing cognitive science, even in a psychology program.

Ultimately, I have tried to keep up my ties to cognitive science throughout my career. I was executive officer of the cognitive science society for 3 years and editor of the journal Cognitive Science for 9 years.

What would you say have been the most important developments within the field of cognitive science since your professional interest in the subject began?

Many of the advances in artificial intelligence that we are seeing now have their roots in cognitive science. Large scale intelligent systems like IBM's Watson and the CYC project have drawn on cognitive science. The connectionist models that emerged from cognitive science in the '80s and '90s are now being used in other computer applications like the deep learning systems that Google is using. Cognitive science is involved in both the technology associated with driverless cars as well as the high-level ethical issues like how a driverless car should make decisions in situations that might lead to a loss of life.

|

Cognitive science has also helped to provide a comprehensive understanding of aspects of language. Bringing together linguistics, psychology, and computational methods has led to developments that would have been hard to get within only a single discipline. Many of the natural language computer systems that are starting to come out now (including systems like Siri and the Amazon Echo) have their roots in cognitive science. |

|

Probably the most important aspect of the field is that it has always been a great place for people to try out new ideas that don't fit the mold of what is being done within the component disciplines of the field. Over time, these ideas may become accepted within the mainstream of one or more of the cognitive science disciplines, but when the ideas are just emerging, cognitive science is a supportive place for people to work on them.

You run the Similarity and Cognition Lab at the University of Texas at Austin, could you tell us something about the kind of research undertaken there?

The main areas of research in my lab have been focused on comparison, categorization, decision making, and motivation.

My early work examined how people determine that things are similar. A big focus of this work was on the kinds of differences that emerge from comparisons. There are two kinds of differences: alignable differences are those that are related to what things have in common, while nonalignable differences are aspects of one item that have no correspondence at all in the other. For example, when comparing a car to a motorcycle, the fact that cars have four wheels and motorcycles have two wheels is an alignable difference. The fact that cars have seatbelts and motorcycles don't is a nonalignable difference. Our research suggests that alignable differences are easier for people to find than nonalignable differences, and they are given more weight in similarity comparisons than nonalignable differences.

We extended this work into decision making and found that the alignable differences among options form a core of the reasons people give for the choices they make. Alignable differences of options are also better remembered than the nonalignable differences, and so people use them when learning about different options.

The categorization research in the lab has explored methods for learning categories. Research in psychology has often focused on a classification task in which people learn about new items by guessing what category they belong to and getting feedback. This task tends to focus people on differences among the items being learned in order to reliably distinguish members of one category from members of other categories. We developed an inference learning task in which people are told the category to which an item belongs and have to predict what features it has. This task focuses people on what members of a category have in common. We also explored what people learn about categories when communicating with them. This work shows that communicating with other people tends to synchronize category structures across individuals.

Finally, we have been interested in motivation. People don't do anything unless they are motivated to do so, but studies in cognitive science and cognitive psychology tend to leave motivational variables uncontrolled. In decision making work, we find that when a particular goal becomes active, it increases the desirability of items that will help to achieve the goal (which we call valuation) and decreases the desirability of items that are unrelated to the goal (which we call devaluation). In addition, we have done a lot of work looking at differences in the cognitive strategies people use depending on whether they are trying to achieve a positive outcome or to avoid a negative outcome.

What can readers expect from your Psychology Today blog 'Ulterior Motives?'

I have been writing my blog for Psychology Today since 2008. I take recently published papers in the psychology literature and put them into a broader context. I also try to describe the studies in enough detail that readers can get a sense of how the researchers supported their position. Each blog entry also includes a link to the original paper for people interested in getting more information.

Could you tell us about your latest book Brain Briefs?

About three and a half years ago, Bob Duke (a colleague of mine at the University of Texas) and I were invited to do a radio show on our local NPR station. The show - called Two Guys on Your Head - is also available as a podcast. It consists of 7 and a half minute segments that talk about a variety of topics ranging from grief to happiness to decision making to why kitten videos are so much fun.

After doing the show for a few years, we decided to put together a book for people who wanted just a little more information about topics than we can give in the show. Brain Briefs answers 40 questions in short chapters. The radio show has often been compared to the NPR classic Car Talk, because we tend not to take ourselves too seriously. The book tries to capture that tone. We were hoping that people would have fun while they learned something.

Is there a particular reason why "we ask people to think for a living but we don't teach them anything about how the mind works?"

The modern science curriculum got laid down in the early 20th century as we were starting to create a broad-based public education system. At that time, the three mature sciences were biology, chemistry, and physics. Psychology had been around as a science for only a short period of time, and so it didn't make the cut. To this day, most of the focus in science in K-12 education remains in biology, chemistry, and physics. As a result, people don't learn a lot about how their minds work. This is particularly important now, because many of the most important jobs require people to use knowledge and to inspire others to think effectively. I believe people would benefit from understanding more about their own minds.

As executive editor of the journal Cognitive Science and someone who has published over 150 scholarly works, what has been your take on the debate surrounding the 'replication crisis' in psychology?

Over the past 25 years, there have been two unfortunate trends. First, starting with the journal Psychological Science, there have been an increasing number of journals offering brief report options, which encourages people to run just a couple of studies and publish a paper. Prior to that, the high-impact journals tended to require 4-ish studies for a paper to be considered. That encouraged people to run several versions of experiments. On top of that, the ability to publish many papers rapidly led to an escalation in the number of papers people were expected to publish in order to get jobs. That led to a focus on pumping papers out rather than really understanding phenomena.

Second, there was increasing emphasis on novel findings rather than the deep development of existing ideas. Unfortunately, novel findings that make you sit up and say "wow" are few and far between. Most of science involves understanding the details of existing phenomena.

I think these factors contributed to the 'replication crisis.' My hope is that people will be encouraged to take a bit more time and care with their work. The empirical basis for the field is the most important thing we have. Theories will come and go, but good data ultimately provide the collection of phenomena that need to be explained. After all, a theory is really only good if it leads you to ask new questions and to collect new data.

That said, there is still an important base of work in the field that does replicate, and so I am not concerned about the long-term health of the field.

Why is smart thinking like chess?

Chess is a game that people can only play by developing expertise. A lot of that expertise involves knowledge of different kinds of strategies that need to be flexibly applied to game situations. That is a microcosm of smart thinking. The smartest thinkers are the ones who learn about how the world works and then develop ways to apply that knowledge when they need to. My book Smart Thinking focuses on helping people to understand how to do that most effectively.

Given your passionate interest in communicating insights from cognitive science to as broad an audience as possible, have you found that certain topics appear to resonate with the general public more than others?

The blog entry I wrote for Psychology Today that has gotten more hits than any other is on Déjà Vu. I do think people are interested in the strange experiences they have. But, people also enjoy finding out about interesting ways to harness their own psychology. For the past few years, I have been writing for Fast Company. The most popular piece I wrote for them examined reasons why To Do lists are beneficial, even if you don't use the list later. And finally, I have written a couple of blog entries on narcissism. For some reason, people seem to be endlessly fascinated by the concept.

Great talk by Dr. Art Markman on key strategies for communicating science to the public effectively.

If you had to choose a favorite episode from your 'Two Guys on Your Head' podcast, which one would it be and why?

My favorite episode was probably one we did earlier this year on why we hate TED talks. The episode was meant to be a bit tongue in cheek, but it seemed to have touched a nerve. We got more positive and more negative feedback on that episode than any other we have done. Early on in the show, we did one on writer's block that I also like a lot. The concepts from that episode have come up in a lot of the live episodes we do.

Connect With Dr. Art Markman

Recent Articles

-

Sponsor a Psychology Website with Over a Million Yearly Visitors

Jun 30, 25 11:30 AM

Showcase your brand to a huge, engaged audience. Discover how to sponsor a psychology website trusted by over a million visitors a year. -

Unparalleled Psychology Advertising Opportunities

Jun 29, 25 04:23 AM

Promote your book, podcast, course, or brand on one of the web's leading psychology platforms. Discover advertising and sponsorship opportunities today. -

Psychology Book Marketing

Jun 29, 25 04:19 AM

Psychology book marketing. Ignite your book's visibility by leveraging the massive reach of the All About Psychology website and social media channels.

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.Go Back To The Psychology Expert Interviews Page

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.