Psychology Classics On Amazon

Aloneness vs Loneliness: Understanding

the Psychological Difference

Introduction

Loneliness has been called a “loneliness epidemic” in recent years, prompting public health warnings about its impact on mental and physical well-being. Yet being alone (aloneness or solitude) is not inherently the same as feeling lonely. Many people willingly seek solitude for reflection or creativity, experiencing it as positive “me time,” while others may feel lonely even in a crowd. This article explores the distinction between aloneness and loneliness, drawing on psychological theory and research to clarify their definitions, causes, and consequences. We will differentiate the concepts, review key theories (from Weiss’s typology of loneliness to Bowlby’s attachment theory and existential perspectives of Fromm and May), compare emotional and cognitive impacts (such as links to depression, creativity, and the “social pain” of loneliness), and discuss neuropsychological findings. Developmental stages and cultural differences in experiencing solitude versus loneliness will be examined, alongside real-world examples (from adolescent struggles to older adult isolation and the unique context of COVID-19 lockdowns). We will also discuss clinical approaches and interventions (e.g. cognitive-behavioral therapy for loneliness and programs to foster social connection), include a table comparing aloneness vs. loneliness, address societal misconceptions about solitude, and conclude with implications for mental health and directions for future research.

Defining Aloneness vs. Loneliness

Aloneness (Solitude) – A Chosen State. Aloneness refers to the state of being by oneself, physically apart from others. Importantly, solitude is often chosen or experienced without distress. It can be a neutral or even positive state of “peaceful aloneness” when it aligns with one’s preference. Psychologists define solitude as time spent alone by choice that does not involve feeling lonely. It is an objective state (one can count the hours spent alone) and does not carry an emotional judgment by itself. When embraced, solitude can provide a sense of freedom, time for self-reflection, and recovery from social stimulation. For example, an artist might spend long hours alone in a studio and feel content and energized by this solitude. Classic existential thinkers like Erich Fromm even argued that developing comfort with being alone is essential for healthy relationships: “Paradoxically, the ability to be alone is the condition for the ability to love”, suggesting that those who can be at peace with themselves are better able to connect authentically with others.

Loneliness – A Subjective Feeling. In contrast, loneliness is a subjective, distressing experience stemming from a perceived gap between desired and actual social connection. One widely used definition describes loneliness as perceived social isolation – the feeling that one’s relationships are inadequate in quantity or quality to meet one’s emotional needs. It is an emotional state, not defined by the objective amount of time one is alone, but by the felt lack of connection. Loneliness is often accompanied by feelings of sadness, emptiness, or longing for companionship. Notably, loneliness can occur even when one is not physically alone (for instance, feeling lonely in a crowd or within an unfulfilling relationship) because it is rooted in subjective perception. Psychologist Robert Weiss (1973) influentially distinguished between two forms of loneliness: emotional loneliness, arising from the absence of a close attachment or intimate relationship (such as the loss of a spouse or best friend), and social loneliness, arising from the absence of a broader social network or sense of belonging to a group. Emotional loneliness involves the deep ache of missing an intimate figure, whereas social loneliness is more of a generalized emptiness from lacking friendships or community. In either case, loneliness is “more than just being alone – it’s feeling disconnected”. It is inherently negative and distressing: people experiencing loneliness often report pain and psychological anguish, in line with Weiss’s description of loneliness as a “gnawing” and undesirable condition. For example, a college student might be surrounded by roommates and classmates yet feel profoundly lonely if they lack close friends or meaningful interactions, illustrating that loneliness is about perceived connection, not physical solitude.

To summarize the key differences between aloneness and loneliness, Table 1 provides a comparative overview:

| Aspect | Aloneness (Solitude) | Loneliness |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | State of being physically alone; often a chosen or neutral condition. | Subjective feeling of distress due to perceived isolation or inadequate social connections. |

| Volition | Often voluntary (by choice); the individual wants or doesn’t mind being alone. | Usually involuntary; the individual does not want to feel this lack of connection. |

| Emotional Tone | Can be positive or neutral – associated with peace, contentment, or relief. | Negative and distressing – associated with sadness, emptiness, and longing. |

| Subjective vs. Objective | Largely objective – a quantifiable state of being alone, with no necessary emotional impact. | Entirely subjective – a psychological state based on perceived lack of connection. |

| Key Cause | Often chosen for rest, reflection, creative pursuits, or personal preference for low stimulation. | Caused by unmet social needs or discrepancy between desired and actual relationships. |

| Potential Benefits | Offers time for self-reflection, emotional renewal, creativity, and stress relief. | None directly; may signal the need to seek connection, prompting social action. |

| Potential Risks | If excessive or undesired, it can lead to loneliness or social skill decline. | Linked to depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, and increased health risks. |

| Example Scenario | An author retreats to a cabin alone and feels peaceful and productive. | A student surrounded by people feels lonely due to lack of meaningful connection. |

Psychological Theories and Perspectives

Understanding aloneness and loneliness requires insight from several psychological theories:

- Weiss’s Typology of Loneliness (Emotional vs. Social): As noted above, Weiss (1973) differentiated loneliness into two types. Emotional loneliness results from the absence of an attachment figure – for example, a person mourning the death of a spouse experiences emotional loneliness due to the loss of that singular deep connection. This form of loneliness is closely tied to attachment theory (discussed below) because it highlights how the disruption of a close bond yields intense isolation distress. Social loneliness, on the other hand, comes from lacking a social network or community. For instance, someone who moves to a new country might have no friends yet and feel socially lonely even if they are not missing any one specific person. Weiss proposed that these two forms have different qualities: emotional loneliness often produces feelings of abandonment and anxiety, whereas social loneliness leads to feelings of boredom and marginalization. Subsequent research supports this bi-dimensional view. Both types can co-occur, but emotional loneliness tends to have stronger links to depression than social loneliness. Weiss’s typology helps clinicians tailor interventions – for example, emotional loneliness might be addressed by grief therapy or fostering a new intimate relationship, while social loneliness might be helped by expanding one’s social network or group involvement.

- Bowlby’s Attachment Theory: Attachment theory provides a developmental lens on loneliness. John Bowlby’s theory posits that humans are born with a need to form close bonds; secure attachment in childhood (a reliable, responsive caregiver) gives a child a sense of safety whether others are present or not. Individuals with secure attachment styles generally find it easier to be alone without feeling lonely, because they carry an internalized sense of trust that others are available when needed. In contrast, insecure attachment styles can predispose people to loneliness. For example, an anxiously attached individual, who fears abandonment, might feel lonely very quickly when alone or perceive rejection even in minor separations. An avoidantly attached individual might withdraw from others to avoid intimacy, potentially leading to social isolation and underlying loneliness despite appearances of self-sufficiency. Research has shown that secure attachment is negatively associated with loneliness, whereas anxious and avoidant attachment are linked to higher loneliness. In one study, college students with higher attachment anxiety reported greater loneliness, partly mediated by low self-esteem and poor social support. Bowlby’s idea of the “internal working model” of relationships means that those who have learned that others can be trusted and that they themselves are worthy of love are less likely to interpret aloneness as a sign of personal failure or to feel the pain of loneliness as often. Conversely, those with attachment trauma or loss may experience what psychiatrist John Cacioppo termed “chronic loneliness,” where they remain lonely even in relationships due to deep-seated fear and hyper-vigilance for social threats. Attachment theory thus helps explain individual differences in how being alone is experienced – some find it comfortable (seeing it as temporary and self-chosen) while others find it intolerable (triggering fears of abandonment).

- Existential Psychology (Fromm and May): Beyond social relationships, existential theorists consider loneliness in terms of the human condition. Erich Fromm and Rollo May, for instance, offer perspectives on the meaning of aloneness. Fromm observed a paradox: while humans dread isolation, the capacity to be alone underlies the capacity to love and be authentic. In The Art of Loving, Fromm argued that mature love requires a sense of self and individuality – one must overcome the fear of aloneness to avoid clinging or dependent relationships. As mentioned, Fromm wrote that the ability to be alone is a prerequisite for the ability to love. He also noted that the “deepest need” of a person is to overcome separateness, to escape the “prison of aloneness” through genuine union with others (while still retaining one’s identity). This view frames loneliness as an existential problem: each person is fundamentally alone in their subjectivity, and finding meaningful connection is a core human motivation. Rollo May similarly highlighted the constructive potential of solitude alongside the anxiety it can evoke. May famously stated, “In order to be open to creativity, one must have the capacity for constructive use of solitude. One must overcome the fear of being alone.”. This emphasizes that creativity and self-discovery flourish when one can tolerate and even embrace solitude rather than experience it as loneliness. Existential perspectives thus draw a line between isolated loneliness, which can be despairing, and solitude, which can lead to self-realization. These thinkers also point out that modern society’s busyness and distraction might be, in part, an attempt to avoid facing aloneness. When solitude is seen as something to fear, people may prefer even shallow social interactions to being alone, which can paradoxically lead to feelings of loneliness if those interactions lack meaning. In therapy, existential psychologists might encourage clients to confront the feelings of loneliness directly and find personal meaning in solitude, transforming it from an aversive state to an opportunity for growth.

- Mindfulness Perspectives: In recent years, mindfulness and acceptance-based approaches have offered insight into coping with loneliness and cultivating positive solitude. Mindfulness involves being present and nonjudgmental about one’s experiences, including the experience of being alone. Rather than immediately labeling time alone as “lonely” or frightening, a mindful approach encourages observing one’s thoughts and feelings about solitude. Research suggests that mindfulness can buffer against loneliness. For example, an 8-week mindfulness meditation training was found to reduce self-reported loneliness in older adults and even reduced inflammatory markers in their immune system. By reducing rumination and negative thinking, mindfulness may prevent the escalation of transient aloneness into painful loneliness. A 2024 study proposed that mindfulness moderates the link between loneliness and depression, helping lonely individuals cope better. Additionally, reframing techniques grounded in mindfulness and cognitive reappraisal have shown promise. In one experiment, people with high loneliness were asked to spend 10 minutes alone after reading different prompts: those who read about the benefits of solitude (a mindful reappraisal, essentially) experienced more positive emotion during the alone time compared to those who got no such reframing. The researchers concluded that “lonely individuals can more readily reap the emotional benefits of solitude when they reframe solitude as an experience that can enhance their well-being”. This finding aligns with mindfulness principles – changing one’s mindset about being alone (viewing it with openness and curiosity rather than dread) can change the emotional outcome of solitude. Mindfulness practices can also alleviate the sting of social pain (discussed below) by fostering an accepting attitude toward momentary loneliness, preventing a spiral of self-criticism (“I’m alone because I’m unlovable”) and instead allowing the feeling to pass. In sum, the mindfulness perspective differentiates being alone from feeling lonely by encouraging a present-focused, accepting mindset that can convert solitude into a positive or at least neutral experience.

Emotional and Cognitive Impacts of Loneliness vs. Solitude

Aloneness and loneliness have markedly different impacts on emotional well-being and cognitive processes.

Emotional Impacts – From Depression to Inspiration: Loneliness is strongly associated with negative emotional states. Chronically lonely individuals often report higher levels of depression and anxiety. Longitudinal studies have found that loneliness can predict later depression, even after accounting for baseline depressive symptoms. This suggests loneliness isn’t just a symptom of depression; it can be a contributing cause. The emotional pain of loneliness can be severe – so much so that neuroscientists describe it as social pain. Brain imaging research reveals that feeling socially rejected or excluded activates some of the same brain regions involved in physical pain, such as the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). In other words, the distress of loneliness “hurts” in a very real, neural sense; for example, an fMRI study showed that being ignored in a virtual ball-tossing game elicited ACC activation similar to physical pain stimuli. This overlap may explain why people use phrases like “heartache” to describe loneliness. Emotionally, loneliness also correlates with feelings of low self-worth and hopelessness, especially when it persists. Lonely individuals can become caught in a negative feedback loop: loneliness can make one feel unworthy or pessimistic about social interaction, which in turn makes reaching out harder, deepening the loneliness – a phenomenon sometimes called the loneliness loop or “loneliness feeds on itself” effect. Additionally, loneliness can co-occur with anger or resentment at being excluded, and in some cases can contribute to aggression or withdrawal in social situations (as a maladaptive coping mechanism).

Aloneness, when it is healthy solitude, tends not to produce these negative emotions – in fact, it can have positive emotional effects. Periods of solitude can bring relief from social pressures and a calming of strong emotions. By stepping away from the demands of relationships or the need to constantly present oneself, individuals often experience lower arousal and a reset of their emotional state. For example, taking a solitary walk in nature or spending a quiet evening reading can reduce feelings of anger or stress built up during a busy day. Many people report feeling recharged and more balanced after some alone time. Solitude can also create a safe space to process emotions – to grieve in private, to reflect on life, or to simply enjoy one’s own company without judgment. Notably, intentional solitude has been linked to increased positive affect in some studies. Psychologists refer to “positive solitude” as the experience of chosen time alone that is refreshing and associated with well-being, not loneliness. This positive solitude allows connection with oneself: one might journal to sort through feelings or engage in prayer or meditation to foster inner peace. In contrast to the sadness of loneliness, positive solitude can bring about feelings of serenity, inspiration, or gratitude. Of course, solitude can also have negative emotional impacts if it is unwanted – prolonged aloneness against one’s will can shift into loneliness and depression, as seen in extreme cases like solitary confinement. The key differentiator is the element of choice and satisfaction: solitude that is desired generally supports emotional health, whereas loneliness by definition entails emotional suffering.

Cognitive Impacts – Biases and Creativity: Loneliness not only affects how people feel, but also how they think. Chronically lonely individuals often develop cognitive biases that reinforce their loneliness. They may become hyper-vigilant to social threats – for instance, assuming others will reject them or interpreting neutral comments as negative. Psychology Today reports have noted that lonely people might even struggle to recognize positive social cues; one piece described how loneliness can distort social perception, such that lonely individuals “can't see when other people are admiring them or showing them affection”. This kind of distorted thinking can create a self-fulfilling prophecy: expecting rejection or lack of care, the lonely person might withdraw or behave anxiously, which can in turn alienate others. Cognitive neuroscientists have also found differences in how lonely brains operate. A systematic review of the neurobiology of loneliness found altered function in brain regions involved in attention and the “default mode” (the network active when our mind wanders). Some studies suggest that lonely people’s brains may become wired to be on alert, scanning for social danger, which might impede concentration and memory. Indeed, loneliness in older adults has been linked to faster cognitive decline and a higher risk of dementia. This could be due to both direct effects (e.g. increased stress hormones damaging the brain) and indirect effects (lonely individuals may engage in fewer stimulating activities). Thus, one cognitive impact of loneliness is impaired cognitive function over time, potentially via increased stress and reduced opportunities for mental engagement.

On a more positive note, experiencing some loneliness or solitude can also spur cognitive and creative processes under certain conditions. Many great works of art and literature have emerged from periods of solitude. Rollo May’s quote above highlights the link between solitude and creativity. When free from social distractions, individuals can enter states of deep focus or “flow” on creative tasks. Research supports the idea that solitude can boost creativity, especially when it is not driven by fear. A University at Buffalo study distinguished between different motivations for social withdrawal and found that a form of withdrawal termed “unsociability” – defined as preferring to spend time alone out of enjoyment of solitude, not due to anxiety – was positively related to creativity. In this study, unlike shyness or avoidance (which were linked to negative outcomes), unsociability was associated with greater creative thinking and no negative socioemotional effects. The researchers concluded that “motivation matters” in withdrawal: choosing solitude for constructive reasons can provide the mental space for imagination and problem-solving. Other studies have echoed that anxiety-free alone time fosters creative thinking. Anecdotally, writers and inventors from Nikola Tesla to J.K. Rowling have credited solitude as the crucible for their ideas. Cognitively, solitude allows the mind to wander freely (which can incubate creative insights) and to deeply immerse in a task without fear of social judgment. In contrast, loneliness, especially if it is distressing, may consume mental resources with worry and rumination, thereby stifling creativity and clear thinking. It’s important to note that balance is key: extended social isolation that turns painful will likely hamper cognitive function (as seen in extreme cases where isolation leads to cognitive disorientation), whereas moderate solitude interspersed with social connection tends to be optimal for creativity and mental health.

Neuropsychological and Biological Findings

Advances in social neuroscience have begun to illuminate how loneliness and social connection (or lack thereof) manifest in the brain and body. Loneliness, especially chronic loneliness, is associated with distinct neurobiological patterns. A 2021 systematic review identified several brain regions where lonely individuals show differences in structure or activity. Key findings suggest that loneliness is related to alterations in the prefrontal cortex (involved in executive function and emotion regulation), the insula (related to emotional awareness and social pain), the amygdala (involved in fear and emotional processing), and the hippocampus (memory and stress regulation). For example, some MRI studies have found that people who report high loneliness have reduced gray matter volume in portions of the prefrontal cortex and amygdala. One interpretation is that lack of social stimulation or chronic stress from loneliness might lead to these brain changes, or conversely that some neural patterns might predispose a person to feel lonely. Additionally, loneliness has been linked to increased activity in brain areas when viewing social threats or stressors, suggesting lonely people may have heightened neural reactivity to negative social information.

Neuroendocrinology provides more clues: Loneliness is a stressor that can trigger the release of stress hormones like cortisol. Chronically lonely individuals often show higher basal levels of cortisol and markers of inflammation. This ties into why loneliness is a health risk – prolonged activation of stress pathways can contribute to heart disease, lowered immunity, and other illnesses. In fact, the U.S. Surgeon General’s report notes that loneliness and social isolation elevate risk for cardiovascular disease and even early mortality at rates comparable to well-known health hazards like smoking and obesity. Part of this effect is likely mediated by how loneliness “gets under the skin” via neurophysiological stress responses.

From a neuropsychological perspective, researchers have also examined how the brain differentiates between physical and social pain. A fascinating line of work suggests overlap, as mentioned, in the neural alarm system for physical pain and the experience of rejection. However, newer research nuances this: while earlier studies pointed to the dorsal ACC as a shared site for social and physical pain, some recent work indicates that it’s more about the salience of the experience rather than pain per se. Nonetheless, the subjective experience of loneliness can indeed feel “painful,” and our brain’s social attachment system – which likely evolved to keep us connected to caregivers and group members for survival – sends distress signals when we are isolated. Evolutionary psychologists theorize that loneliness is analogous to hunger: just as hunger signals a need for food, loneliness signals a need for social contact. This is adaptive in moderate amounts (prompting us to reconnect with others), but if the need cannot be met, the chronic signal (loneliness) leads to wear-and-tear on the body and brain.

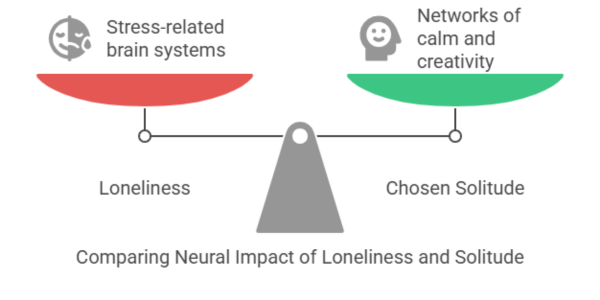

Interestingly, being comfortably alone (solitude) does not trigger these alarm systems. When solitude is experienced as positive, the brain may show patterns akin to relaxation or creative focus (e.g. increased alpha wave activity linked to calm, or activation of default mode network which can correlate with introspection and imagination). There is some evidence that people who are content in solitude might even have differences in brain connectivity – for instance, one study found that people who scored high on a measure of positive solitude had neural signatures suggesting better ability to switch between social and non-social thinking modes, though this research is nascent.

In summary, neuropsychological research reinforces the distinction: loneliness is a state of threat and distress that mobilizes stress-related brain systems and can even alter brain structure over time, whereas chosen solitude is more likely to engage brain networks of calm, reflection, or creativity without the same stress activation. Ongoing studies, including large-scale brain scans, are investigating how training the brain (through interventions like meditation or therapy) might mitigate the negative neural impact of loneliness or enhance the benefits of solitude.

Developmental Stages and Cultural Differences

Across the Lifespan: From Childhood to Old Age. The experience of loneliness and attitudes toward solitude change over the course of development. In childhood, loneliness is often linked to peer acceptance and attachment to parents. Young children may not label “loneliness” as such, but they experience it as sadness when they feel left out or when separated from caregivers. Research by Asher and colleagues finds that even school-age children can feel lonely at school if they have difficulty making friends or are bullied, and such loneliness can impact their academic and emotional development (e.g. lonely children might withdraw further, creating a cycle). Children’s ability to be alone comfortably is influenced by the security of their attachment; a securely attached child can tolerate solitude (e.g. playing alone) knowing their parent will return, whereas an insecurely attached child might become very distressed when alone.

In adolescence, the issues of aloneness and loneliness become particularly pronounced. Teenagers usually crave independence and time away from parents, often seeking solitude in their room as a way to assert autonomy or explore their identity (a form of healthy aloneness). At the same time, peer belonging is paramount in adolescence, so loneliness can be acutely painful if they feel socially rejected or alienated. It is common to hear teens talk about feeling “alone” in terms of not being understood by others. Indeed, a study of adolescents’ perceptions of aloneness versus loneliness found that many teens actively value alone time for creativity or relaxation, but they also fear the stigma of being seen as a “loner”. Solitude can serve as a respite from the intense self-consciousness that comes with adolescent social life; for instance, a teen might listen to music alone to regulate emotions after a stressful day at school. However, prolonged loneliness in adolescence is a risk factor for mental health problems like depression, and it can stem from experiences like being excluded by peers or unrequited young love. Adolescence is also when lifelong social habits form – a teen who learns to balance social interaction and solitude is likely to carry that into adulthood, whereas teens who experience extreme social isolation may struggle with social skills or fear of intimacy later on. Interventions in schools (such as peer mentoring or inclusion programs) can be crucial to address loneliness during these formative years.

In adulthood, experiences of solitude and loneliness diversify. Young adults often face a challenging transition: leaving home for college or work can increase loneliness due to the disruption of old social networks. Paradoxically, emerging adults are frequently surrounded by people (in dorms, universities, or new workplaces) yet might feel lonely until they form new meaningful connections. This age is also when many people actively choose solitude for the first time – for example, traveling alone, living in a studio apartment, or pursuing solitary hobbies – which can be empowering or scary. As adults progress into midlife, careers and family obligations dominate. Some may struggle to find time alone (e.g. busy parents rarely get solitude and might yearn for a quiet moment), whereas others may struggle to find time to socialize (leading to loneliness, for example, a single professional who works long hours might feel isolated). Midlife loneliness can occur due to relationship breakdowns (divorce can lead to both emotional loneliness from loss of a partner and social loneliness if couple-friends drift away) or due to relocating for jobs. On the other hand, many adults at this stage learn to enjoy whatever pockets of solitude they can find – using a long solo commute to listen to podcasts or reflect, for instance.

In older adulthood, the dynamics of solitude and loneliness shift significantly. Social networks tend to shrink as people retire, children move out, and friends or spouses pass away. Consequently, older adults are at particular risk for loneliness due to both emotional losses (widowhood being a prime cause of profound loneliness) and social isolation (living alone, mobility issues, or smaller social circles). Indeed, the University of Arizona EAR study found that beyond a certain threshold of time alone (about 75% of one’s waking hours), it becomes very difficult to avoid loneliness – and this threshold is often crossed by older adults living alone. The same study noted a strong association between being alone and feeling lonely among adults over 68, with about a 25% overlap between time alone and loneliness in that group (compared to only ~3% overlap in younger adults). This suggests that for older individuals, increasing aloneness more readily translates into loneliness, likely because their alone time is less often by choice and because opportunities for social interaction are fewer. However, it is important not to generalize too much – many seniors report high satisfaction in solitude. Some research even indicates that older adults can be more content being alone than younger people, possibly due to a lifetime of developing coping skills and perspective. For example, an elderly person might cherish quiet time gardening or reading as a welcome contrast to a youth spent in constant company. There is also evidence that loneliness is not uniformly higher in older populations; some national surveys show loneliness peaks in adolescence and young adulthood, dips in middle age, and can rise again in the oldest-old. Thus, while many older adults face loneliness (especially the isolated and very old), others thrive in peaceful solitude. Culturally, older generations may also have different attitudes – they might see loneliness as a private matter not to complain about, or they might have grown up more accustomed to solitude than younger, hyper-connected generations. Regardless, because loneliness in old age has serious health implications (it is linked with cognitive decline and is a strong predictor of mortality), a lot of attention is now given to interventions for seniors (e.g. senior centers, telephone befriending programs, companion robots, etc., discussed later).

Cultural Differences: Culture plays a complex role in experiences of aloneness and loneliness. One might assume that individualistic societies (which value independence and self-reliance) would have more positive views of solitude and possibly more loneliness, whereas collectivistic societies (which value community and interdependence) might encourage togetherness and have less loneliness. To some extent, research supports these trends – but with caveats. Cross-cultural studies have found that rates of reported loneliness do vary between countries, though not always as expected. For example, one large survey covering many nations found that rates of loneliness were actually comparable or even higher in some collectivistic cultures as in individualistic ones. It appears that loneliness is a human experience everywhere, but cultural norms influence how it is perceived and discussed. In cultures like the U.S. and U.K. (highly individualistic), there is often a stigma about admitting loneliness because self-sufficiency is prized, yet ironically these cultures have publicized a “loneliness epidemic” in recent years and even created political roles like a Minister of Loneliness (in the U.K.). In more collectivist societies (e.g. many Asian, African, or Latin American cultures), family and community bonds are expected to be strong, so being alone is less common in daily life. However, when individuals in those cultures do feel lonely, they might feel a strong sense of shame or personal failure due to the high value placed on connectedness. Also, modernization and urbanization have led to increased loneliness in traditionally collective societies – for instance, Japan faces a well-documented issue of social isolation among elders (hikikomori and kodokushi, or “lonely deaths”) despite a communal cultural heritage.

Cultural attitudes toward solitude also differ. In some cultures, solitude is deeply respected – for example, monastic traditions in various religions (Christian monks, Buddhist hermits) treat solitude as sacred and necessary for enlightenment. In Japan, despite concerns about isolation, there is also the concept of “forest bathing” (shinrin-yoku) and Zen meditation, which emphasize the restorative power of solitary communion with nature. In Scandinavian countries, spending time alone in nature (going to a cabin in the woods) is a valued part of life for many, reflecting an acceptance of solitude. By contrast, in very sociable cultures (Mediterranean, Middle Eastern), doing things alone might be viewed with pity – for instance, eating alone at a restaurant might be considered sad, whereas in another culture it’s normal. A 2025 cross-national study by Rodriguez and colleagues found that across nine countries spanning collectivist to individualist orientations, people’s beliefs about solitude significantly shaped their loneliness levels. Remarkably, the benefit of having a positive view of being alone was seen in all these cultures, suggesting a universal element: those who believed solitude can be beneficial felt less lonely after spending time alone, whereas those who believed being alone is harmful felt more lonely after solitude. This implies that, regardless of culture, teaching people to appreciate solitude might help reduce loneliness. Still, cultural nuances matter in how we implement such lessons. For example, in a collectivist context, positive solitude might be framed as strengthening oneself to better serve family, whereas in an individualist context it might be framed as self-care and creativity.

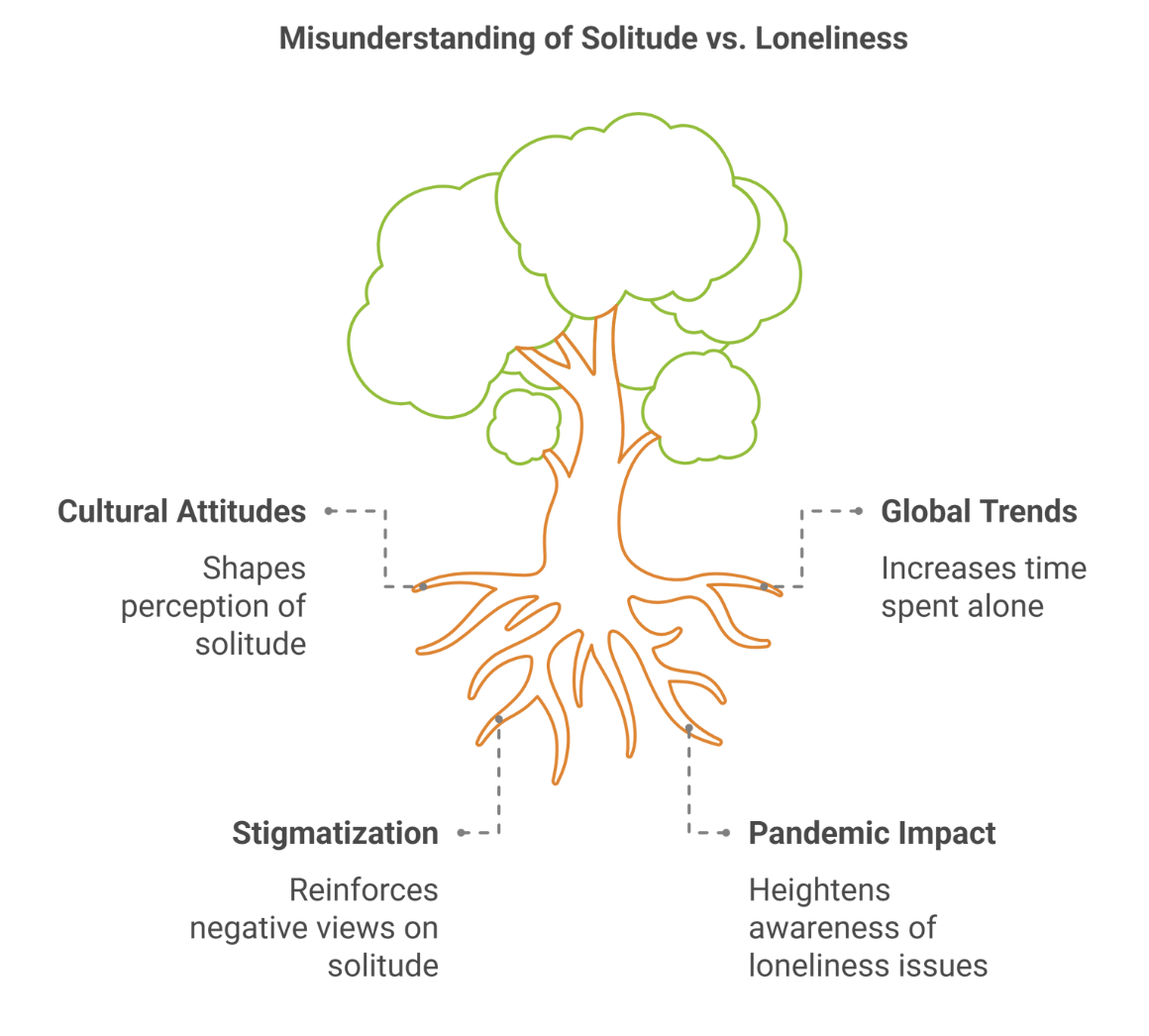

One salient cultural shift globally is the impact of technology and the COVID-19 pandemic (which we’ll discuss next) – virtually every culture had to confront extended aloneness during lockdowns, and this has possibly altered norms around solitude (making video chats an accepted stand-in for physical presence, for instance). Additionally, generational culture intersects with national culture. Younger generations worldwide, sometimes called the “internet generation,” may have a different relationship to solitude and loneliness because they are constantly connected digitally. Some researchers talk about “alone together” – young people might be alone in their room but feel socially engaged through online interactions, blurring the line between solitude and socializing. Meanwhile, older generations might define being alone strictly as having no one physically present. These differences can cause misunderstandings; for instance, parents might worry a teen is “always alone in their room,” not realizing the teen is actually feeling quite connected via social media (though online connection quality varies and can sometimes exacerbate loneliness as well).

In summary, cultural values influence whether aloneness is seen as positive (solitude as virtue or sign of strength) or negative (solitude as sad isolation), and these attitudes can in turn shape people’s experiences of loneliness. Destigmatizing solitude and distinguishing it from loneliness is a challenge many societies face, particularly as global trends (smaller families, more single-person households) point to increased time spent alone. The next section examines a real-world example that affected all ages and cultures: the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced a reckoning with both loneliness and solitude.

Real-World Examples and Case Studies

Real-life events and scenarios vividly illustrate the difference between being alone and feeling lonely. Consider the COVID-19 pandemic: in 2020, public health measures required people worldwide to physically isolate themselves to contain the virus. Overnight, millions experienced a sudden increase in aloneness. For some, this solitude was merely inconvenient or even somewhat welcome (a break from the daily grind), but for many others it led to intense loneliness. A college student sent home from campus, away from friends and the stimulating college environment, might have felt lost and lonely despite being with family, missing the peer interactions that give life meaning at that age. An older adult living alone, who relied on a weekly social gathering at church or a senior center, suddenly cut off from those interactions, might have experienced deep loneliness and anxiety, worrying when they’d see a friendly face again. Studies during COVID-19 found significant increases in self-reported loneliness, especially in populations like young adults and those living alone. However, interestingly, not everyone suffered equally – personality and mindset mattered. People who were able to maintain virtual connections or who had hobbies to occupy their time (reading, gardening, art) often fared better. Some even discovered the “art of aloneness” during lockdown: for instance, a normally extroverted individual might have learned to enjoy daily solitary walks or journaling, gaining a new appreciation for solitude as a result of the pandemic. In contrast, others struggled severely: case reports described adolescents with no outlet for socializing sliding into depression due to loneliness, or long-term care residents feeling despair when family visits ceased. COVID-19, therefore, acted as a natural experiment highlighting how context and coping strategies determine whether enforced aloneness translates into loneliness.

Another case example is the experience of adolescents in the digital age. Take a high school student who is physically surrounded by peers all day at school – they may not be “alone” often, yet if they feel misunderstood or socially anxious, they might experience profound loneliness. They might go home and retreat to online worlds or video games. To a parent, the teen is “alone in their room,” but in the teen’s mind, they might or might not feel lonely depending on their online social connections. If the teen has a supportive online friend group (for example, fellow fans in a gaming community), their time physically alone might not feel lonely at all – it might even be the only time they feel truly connected, ironically. On the other hand, if a teen is scrolling social media and seeing others having fun (the classic “fear of missing out”), they might feel intensely lonely and inadequate. Thus, two adolescents could both be spending their evening alone at home; one feels content in solitude, while the other feels isolated and sad. The difference lies in their sense of connection versus disconnection.

For older adulthood, a telling example is a widow(er) in their 70s. Imagine a woman, Jane, who was married for 50 years and whose husband recently passed away. She now lives alone for the first time in her life. Each evening, she sits in the same living room where she once shared her day with her spouse. Even if her neighbors or adult children visit occasionally, Jane experiences emotional loneliness – a profound sense of absence of that one close companion. This form of loneliness can persist even when she is around others, because the specific attachment bond is irreplaceable (at least in the short term). Over time, Jane might cope by seeking social support through a bereavement group, finding new friendships, or perhaps finding meaning in solitude by engaging in her hobbies and remembering her husband in positive ways. If successful, she might come to appreciate some solitude – for example, quietly tending his beloved garden might make her feel connected to him and at peace rather than lonely. Alternatively, consider John, an 80-year-old man in a nursing home with plenty of people around (staff and other residents) but no deep connections. He may feel “lonely in a crowd,” longing for someone who truly knows him. This highlights that simply providing social contact doesn’t always solve loneliness; the quality and personal significance of relationships matter.

These examples underscore that loneliness is a subjective experience not wholly determined by external conditions. They also show how resilience and coping can turn enforced aloneness into tolerable or even growthful solitude. Adolescents and elders who learn to engage with their alone time – through creativity, spiritual practice, or reframing their mindset – can sometimes transform loneliness into constructive solitude. Conversely, lacking coping strategies or a support system can turn even brief aloneness into a feeling of loneliness.

Clinical Approaches and Interventions

Given the detrimental effects of chronic loneliness on mental and physical health, psychologists and public health experts have developed interventions to reduce loneliness and to help individuals better navigate solitude. On the clinical front, one common approach is Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for loneliness. CBT targets the maladaptive thoughts and behaviors that can accompany loneliness. For instance, a lonely client might have automatic thoughts like “I’m always excluded” or “No one could love me.” In therapy, the clinician helps the client challenge and reframe these cognitions – perhaps examining evidence that some people do care, or that being alone right now doesn’t mean they are fundamentally unworthy. By reducing negative self-talk and social anxiety, CBT can encourage more proactive social behavior (like initiating conversations, or joining activities) to break the cycle of loneliness. One specific CBT technique, cognitive restructuring, directly addresses the person’s beliefs about solitude and social interaction. As the Nature Communications study showed, beliefs about being alone significantly shape loneliness. A therapist might work with a lonely individual to reshape the belief that “being alone means I’m a loser” into a healthier belief like “everyone needs some alone time – being alone right now just means I have an opportunity to do things I enjoy.” This kind of reappraisal can reduce the sting of solitude and make it easier for the individual to use alone time constructively while still working on increasing meaningful connections.

Another therapeutic approach is social skills training and assertiveness training. Some people feel lonely because they have difficulty forming relationships (perhaps due to shyness, autism spectrum, or a lifetime of avoidance). Therapists can help such clients build communication skills, learn to express themselves, and practice initiating social contact. Group therapy can be particularly useful here – in group therapy for loneliness, participants, who all feel isolated, have a chance to connect with each other under the guidance of a therapist. This provides immediate relief (they realize they are not alone in feeling lonely) and a safe space to practice interacting. Over time, group members often form bonds and support each other in making changes outside of therapy, such as making a phone call to a family member or joining a club.

Mindfulness-based interventions are also being applied. As discussed earlier, mindfulness training can reduce loneliness by helping individuals accept their feelings and by breaking cycles of negative thought. Compassion meditation – cultivating feelings of kindness and connection toward oneself and others – can counteract the emotional harshness of loneliness. Some programs teach mindfulness alongside enhancing social connectedness (for example, mindful listening and presence in relationships).

On a community and public health level, there is growing momentum to address loneliness through social connection programs. The U.S. Surgeon General’s 2023 National Strategy to Advance Social Connection is a comprehensive approach targeting loneliness and isolation as public health priorities. This strategy calls for multi-tiered interventions: strengthening community infrastructures that bring people together, encouraging doctors to assess patients’ social well-being, and launching public campaigns to destigmatize loneliness and seeking help. Examples of community interventions include:

- Social prescribing: In some healthcare systems, providers “prescribe” social activities – for instance, a walking group, art class, or volunteer opportunity – for patients who are lonely or socially isolated. This connects individuals to organizations or clubs, giving them regular social contact around a shared interest.

- Befriending programs: These pair volunteers with lonely individuals (often older adults or people with disabilities). The volunteer might make weekly phone calls or home visits, offering companionship and conversation. Research shows such programs can modestly improve feelings of connectedness.

- Structured group programs: Many non-profits and community centers run groups like senior coffee mornings, widow support circles, or “men’s sheds” (community workshops for older men, popular in Australia) to combat social isolation. These provide a sense of belonging and purpose.

- School and youth programs: To prevent loneliness in young populations, schools have implemented peer mentoring (older students buddy with younger ones), social-emotional learning curricula that emphasize inclusion and empathy, and clubs to ensure every student finds a niche. Campaigns like “No One Eats Alone” day in some schools encourage students to include peers who might be isolated.

For those who struggle with the stigma of loneliness or solitude, psychoeducation is important. Many people feel ashamed of being lonely, as if it means they are unpopular or needy. Therapists and public education can normalize the experience – pointing out that roughly 50% of Americans have felt loneliness in recent years, so it is very common and not a personal failing. Likewise, educating the public on the value of solitude can reduce stigma. If people understand that enjoying time alone can be a sign of psychological health and can bring benefits (creativity, stress relief), they may be less likely to tease or pity those who spend time alone. This can help individuals who prefer solitude feel less pressured to always socialize, and help those who are lonely feel less judged as they work on improving their situation.

One interesting intervention angle is leveraging technology to alleviate loneliness without sacrificing the benefits of solitude. During the pandemic, many discovered that video calls, online communities, and even virtual reality can create a sense of social presence across distances. While face-to-face interaction is generally superior for satisfying our deep social needs, these digital forms can be a useful bridge. For example, an isolated elderly person might use a tablet to join a virtual book club – they are physically alone (still getting some solitude) but also virtually with others discussing a shared interest, which can reduce loneliness. Care must be taken, however, as excessive reliance on social media can sometimes worsen loneliness if it leads to superficial interactions or harmful comparisons. Thus, mental health professionals often coach clients on healthy use of technology – using it to connect (e.g. scheduling regular video chats with family, participating in hobby forums) rather than passively consuming others’ highlight reels.

Finally, interventions sometimes aim at helping individuals find solace in solitude as well as build connections. A balanced approach might encourage someone to schedule a couple of social activities per week (to ensure some connection) while also scheduling enjoyable solo activities (to learn that solitude can be fulfilling, not scary). For example, a therapist might suggest the client tries going to a movie alone or taking themselves out to lunch, which can be empowering. Therapeutic writing or journaling can also be prescribed as a way to engage with one’s thoughts and feelings during alone time constructively.

Societal Misconceptions and Stigma around Solitude

Society often sends mixed messages about aloneness. On one hand, Western proverbs extol solitude (“Silence is golden,” or the idea that genius requires lonely toil), but on the other hand, being a “loner” is stigmatized and people are often judged for being alone (for instance, seeing someone dining alone and assuming they are unhappy). One major misconception is that being alone equates to being lonely. This is a false equivalence that this article has hopefully dispelled – one can be alone and perfectly content, or conversely, not alone and very lonely. Yet, popular discourse frequently conflates the two. The media especially has tended to frame solitude negatively in recent years. A content analysis of U.S. news articles (2020–2022) found that stories were 10 times more likely to portray being alone as harmful than as beneficial. Such coverage, likely well-intentioned to highlight the problem of loneliness, may inadvertently reinforce the stigma that spending time alone is undesirable or “bad for you.” In reality, it’s unwanted isolation that is harmful, not solitude by choice.

Because of this deficit view of solitude, people may feel pressure to appear socially engaged. Many individuals stay in constant digital contact or overbook their social calendars not out of desire, but out of fear that choosing downtime will be seen as antisocial. This “collective anxiety about being alone” means that those who actually prefer solitude can be misunderstood. For example, an introverted teenager might genuinely enjoy eating lunch in the library to have quiet reading time, but peers might gossip that they have “no friends.” Such stigma can cause distress both to those who like solitude (making them feel abnormal) and those who are lonely (adding shame to their pain).

Another societal misconception is the idealization of extraversion as “normal.” In many cultures, especially the United States, being outgoing and gregarious is rewarded, and by contrast, preferring solitude is sometimes labeled as a problem. This extraversion bias can marginalize introverts or reflective types. However, society benefits from people who are comfortable being alone – these individuals often become writers, researchers, artists, or others who contribute in ways that require extended solitary effort. The stigma that a person who spends time alone is weird or sad is simply not accurate in many cases. As one Psychology Today article bluntly put it, “Being alone is not the same as being lonely,” and psychology as a field recognizes this distinction.

Furthermore, there’s a misconception that loneliness is an issue only for certain groups (like the elderly) or that it signifies someone is an outcast. The truth is loneliness can affect anyone – popular, well-connected people can feel lonely if they lack intimacy or authenticity in relationships. It is not a character flaw but a human emotion. Public figures from celebrities to CEOs have begun speaking up about their loneliness, which helps reduce the stigma by showing it can “happen to anyone.” The U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy notably wrote about his own bout of loneliness when he started his term – despite holding a prestigious position, he found himself isolated in a new city. This kind of openness helps change the narrative: loneliness doesn’t mean you are socially failing, it means you are human and craving connection.

Society’s deficit-based view is slowly evolving with more conversations about mental health. Movements to “normalize solitude” are emerging. For instance, the popularity of terms like “self-care” and “introvert” pride (e.g., humorous quotes on mugs like “Cannot people today, I’m peopled out”) suggest a growing acceptance that solitude has value and that needing alone time is legitimate. Educational efforts are also aiming to teach the difference between healthy solitude and true loneliness, so people don’t fear being alone per se, but know to be concerned if they feel lonely persistently.

Importantly, addressing misconceptions also involves structural changes – workplaces that expect constant connectivity may need to allow employees breaks or quiet time (encouraging solitude for productivity and well-being), and schools should avoid over-pathologizing solitary behavior (not every child who plays alone is suffering loneliness; some are simply imaginative solo players). By acknowledging individual differences – some thrive with more solitude, others with more social time – society can reduce stigma. In practical terms, this could mean creating physical spaces for solitude (meditation rooms, library nooks) even in communal settings, as well as fostering inclusive social environments for those who do seek connection.

In summary, combating the stigma around solitude and the misconceptions about loneliness is a societal task. Media, education, and public health messaging are starting to stress that loneliness is a subjective pain to be addressed, but solitude is a tool that can be positive. As one researcher put it, “Our relationship with our time alone” is crucial – if we can shift public perception to see alone time as not automatically alarming, people may develop healthier relationships with solitude and be less likely to fall into loneliness as a result.

Conclusion and Future Directions

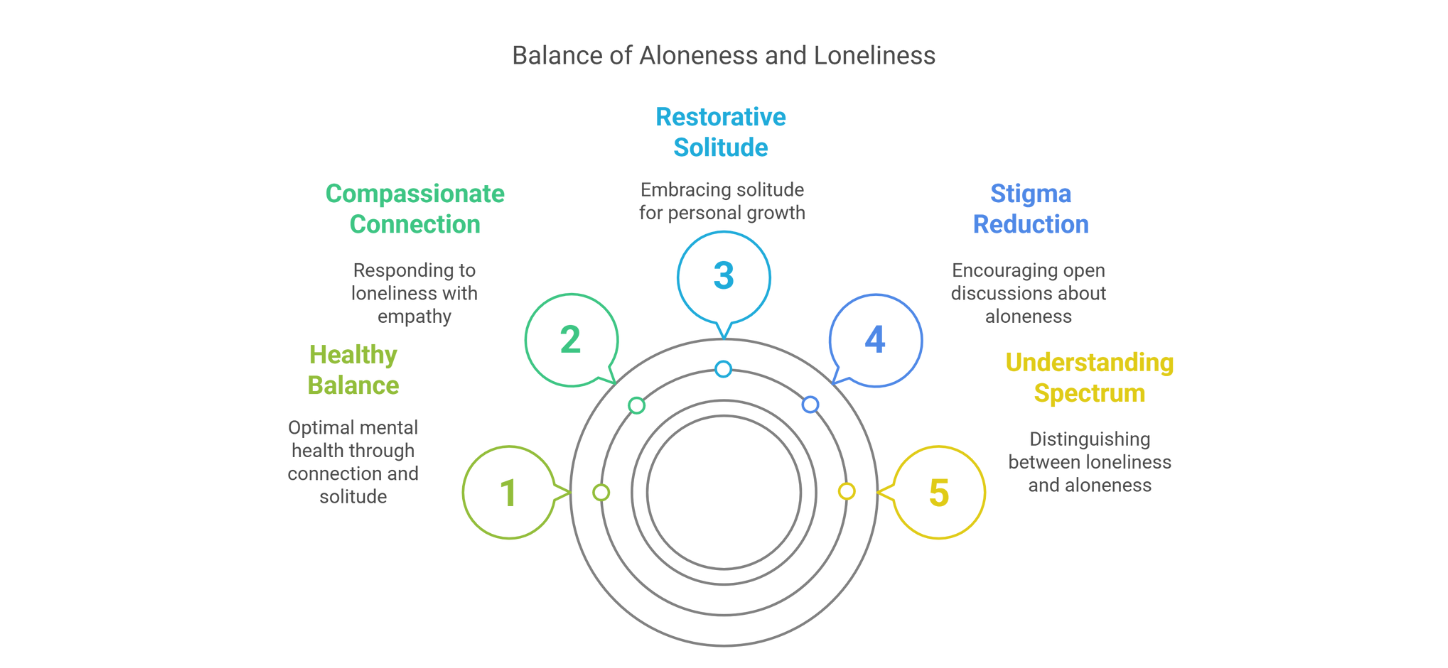

Aloneness and loneliness are related but fundamentally distinct experiences. Understanding this distinction has important implications for mental health. Loneliness, as a distressing feeling of disconnection, can erode well-being and is linked to depression, anxiety, and even physical illness. Aloneness, in the form of chosen solitude, can be neutral or beneficial – offering a chance for rest, creativity, and self-understanding. An awareness of the difference allows individuals and practitioners to promote healthy solitude while combating harmful loneliness. It means we can encourage practices like mindfulness, journaling, or solo hobbies to harness the upsides of alone time, without dismissing the very real need humans have for social bonds.

For mental health professionals, this distinction informs treatment: a client presenting with loneliness might need support in building relationships and altering negative thought patterns, whereas a client who fears being alone might benefit from gradually learning that solitude is safe and even rewarding (perhaps through therapeutic exercises in spending time alone). Societally, reducing loneliness will likely involve both increasing social opportunities and changing how we think about solitude. As the University of Michigan study in 2025 showed, when people learn to view solitude more positively, they actually feel less lonely and more happy in their alone time. This suggests that public health initiatives should not only connect people but also educate about positive solitude – a nuanced strategy that could improve overall well-being.

Future research is poised to delve deeper into these topics. One promising area is the neuroscience of connection: by understanding the neural “signature” of fulfilling social interaction versus the pain of loneliness, we might develop interventions (even pharmacological or brain stimulation techniques) to alleviate the worst effects of loneliness. Additionally, as virtual and augmented reality technologies advance, researchers are asking whether simulated social environments can satisfy social needs or if only in-person contact truly quenches loneliness. Long-term studies following people across the lifespan can help clarify how early experiences with solitude or loneliness shape later outcomes – for example, does a teen who learns mindful solitude cope better with a solitary job decades later? Culturally sensitive research will also be crucial, as we need to know how to tailor anti-loneliness programs to different communities (what works in an American retirement home might differ from what works in a Japanese neighborhood or an Indigenous community, for instance).

Another critical direction is examining the role of creative and productive solitude in an increasingly connected world. With constant digital connectivity, moments of true solitude are becoming rarer unless deliberately taken. Psychologists are interested in whether this impacts creativity, empathy, and self-concept development. There may be a case to be made for “training” people in solitude skills just as we train social skills – especially for younger generations who seldom experience unplugged alone time.

On the intervention side, we anticipate more community design approaches to social connection. Urban planners and policy-makers might consider how housing and city layouts can reduce isolation (for example, multigenerational housing or public spaces that encourage casual social encounters). The Surgeon General’s advisory calls for such structural solutions, recognizing that loneliness is not just an individual problem but one influenced by how our society is organized.

In conclusion, distinguishing aloneness from loneliness enables a more balanced view of human needs: we need meaningful connection with others and time with ourselves. Both are essential for mental health. By reducing the stigma of loneliness (so people can seek help) and of solitude (so people can enjoy time with themselves without guilt), we can foster a society where individuals are better equipped to navigate the spectrum from togetherness to aloneness. As students of psychology and as future practitioners, understanding this nuanced landscape will help in promoting interventions that alleviate loneliness for those in pain, while also encouraging everyone to develop comfort in their own company. Ultimately, the goal is a healthier relationship with solitude that coexists with fulfilling social bonds – a state where being alone is at times a choice that enriches life, and feeling lonely is a signal we respond to with compassion and connection. Future research and action will continue to bridge the gap between these two experiences, ensuring that no one who is truly suffering from loneliness goes unheard, and that the power of restorative solitude is harnessed for well-being.

References (Selected)

Danvers, A. F., Efinger, L. D., Mehl, M. R., Helm, P. J., Raison, C. L., Polsinelli, A. J., Moseley, S. A., & Sbarra, D. A. (2023). Loneliness and time alone in everyday life: A descriptive-exploratory study of subjective and objective social isolation. Journal of Research in Personality, 107, 104426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2023.104426

Murthy, V. (2023). Our epidemic of loneliness and isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s advisory on the healing effects of social connection and community. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-social-connection-advisory.pdf

Sbarra, D. A. (2023, October 2). Why being alone isn’t loneliness. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/.../loneliness-is-not-being-alone

Synnott, A. (2024, January 15). On solitude: Why we need it. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/.../on-solitude-why-we-need-it

Weiss, R. S. (1973). Loneliness: The experience of emotional and social isolation. MIT Press. https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262730419/loneliness

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. Basic Books. https://www.basicbooks.com/titles/john-bowlby/a-secure-base/9780465075973

Fromm, E. (1956). The art of loving. Harper & Row. https://www.harpercollins.com/products/the-art-of-loving-erich-fromm

May, R. (1975). The courage to create. W. W. Norton & Company. https://wwnorton.com/books/The-Courage-to-Create

Cacioppo, J. T., & Patrick, W. (2008). Loneliness: Human nature and the need for social connection. W. W. Norton & Company. https://wwnorton.com/books/Loneliness

Nguyen, T.-V., & Weinstein, N. (2021). Definitions of solitude in everyday life. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/01461672221115941

Rodriguez, M., Schertz, K., & Kross, E. (2025). How people think about being alone shapes their experience of loneliness. Nature Communications, 16, 1594. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-56764-3

Lam, J. A., et al. (2021). Neurobiology of loneliness: A systematic review. Neuropsychopharmacology, 46(11), 1873–1887. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41386-021-01058-7

Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 40(2), 218–227. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8

Armitage, R., & Nellums, L. B. (2020). COVID-19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly. The Lancet Public Health, 5(5), e256. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/PIIS2468-2667(20)30061-X/fulltext

Know someone who would be interested in reading

Aloneness vs Loneliness: Understanding the Psychological Difference.

Share This Page With Them.

Go From "Aloneness vs Loneliness: Understanding the Psychological Difference" Back To The Home Page