Abnormal Psychology

What is Abnormal Psychology?

If you have an interest in abnormal psychology, the first thing you should consider is whether the term itself is still fit for purpose. Historically, the study of abnormal mental phenomena dates back to the late 19th century, with pioneering work by Morton Prince. Prince famously documented the first widely reported case of multiple personality disorder following clinical hypnosis sessions with "Sally Beauchamp," who exhibited three distinct personalities.

In 1905, Prince published his landmark book, The Dissociation of a Personality: A Biographical Study in Abnormal Psychology, and in 1906, he founded the Journal of Abnormal Psychology. The first volume included contributions from luminaries like Pierre Janet and Carl Jung, cementing the field’s foundation. The medicalization of abnormal behavior was born and with it the notion that one could identify, classify and psychopathologize such behavior.

Today, abnormal psychology is defined as the branch of psychology devoted to the study of mental, emotional, and behavioral aberrations. It focuses on the classification, causation, diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of psychological disorders (Arnold Lazarus and Andrew Colman). However, the term has sparked significant debate in recent years.

The Debate: Is "Abnormal Psychology" Still Relevant?

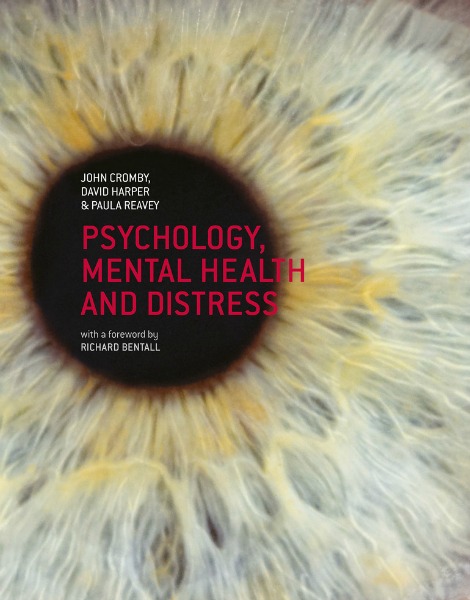

In their award winning book 'Psychology, Mental Health and Distress,' John Cromby, David Harper, Paula Reavey outline a number of compelling reasons why they chose not to state that their book was about 'abnormal psychology.' For instance, the authors note that:

- Subjectivity: There is no objective way to distinguish "abnormal" behaviors and experiences from "normal" ones.

- Medicalization: Abnormal psychology often leans heavily into psychiatry, abandoning psychological perspectives.

- Stigma: Labeling individuals as "abnormal" can be alienating and harmful, especially for those living with mental health challenges.

'

"Kinda sucks if the experiences you live are deemed 'abnormal'" (quote from a discussion on whether 'abnormal psychology' courses should change their name.)

Why the Term "Abnormal Psychology" is Problematic

1. Lack of Clear Boundaries:

What constitutes "abnormal" behavior varies across cultures, time periods, and contexts. For example, hearing voices might be seen as a spiritual experience in some cultures but labeled as psychosis in others.

2. Stigma and Discrimination:

Labeling individuals as "abnormal" can perpetuate stigma, making it harder for them to seek help or reintegrate into society.

3. Overemphasis on Pathology:

Abnormal psychology often focuses on what’s "wrong" with individuals, ignoring their strengths, resilience, and potential for growth.

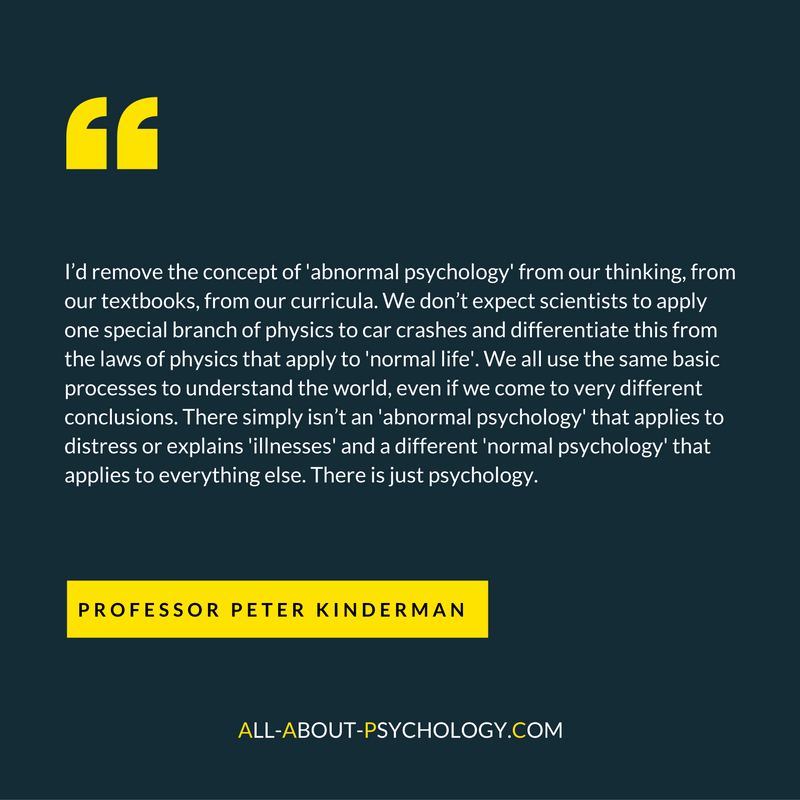

Expert Insights: Professor Peter Kinderman

Peter Kinderman, Ph.D., a leading figure in clinical psychology and former President of the British Psychological Society, has been vocal about his skepticism of the term "abnormal psychology." As Professor of Clinical Psychology at the University of Liverpool, Kinderman’s research focuses on the psychopathology of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and personality disorder. He has developed internationally recognized models of paranoid thought and mania, which inform therapeutic interventions.

Kinderman argues that the concept of "abnormal psychology" is flawed because it pathologizes human experiences without considering the broader social, emotional, and environmental contexts. To help understand his view, here's an edited snippet from his book: A Prescription for Psychiatry: Why We Need a Whole New Approach to Mental Health and Wellbeing.

I commute to work by car and unfortunately drive for quite long distances on motorways. So my journey to work (like, I suppose, everything else in life) depends on the operation of the laws of physics.

When it rains, we often see collisions and other accidental tragedies; the roads are slippery, it is harder to see. When people have accidents, the police investigate the probable or likely cause of the incident for legal and insurance purposes. Their analysis includes human factors, but also includes complex physics.

To work out why a tragedy has occurred, the investigators will calculate things like the velocity of the vehicles involved, coefficients of friction between rubber and tarmac, reaction times calculated using equations of acceleration and deceleration, the role of centrifugal forces, tyre pressures and ‘footprint’, the role of aquaplaning, lift, etc.

They will measure elements of the physical world; the weight of the vehicles, radius of turns, the slope of ascents or descents, whether the conditions were wet or dry, the temperature, tyre pressures, the condition of brakes and the nature of the road surface.

All these aspects of physics are important; they explain why accidents happen. But road traffic investigators don’t use a special branch of physics called ‘abnormal physics’. We don’t expect scientists to apply one special branch of physics to car crashes and differentiate this from the laws of physics that apply to ‘normal life’.

There is not an ‘abnormal coefficient of friction’ that leads to car crashes and a ‘normal coefficient of friction’ that keeps us safe. Instead, and wisely, we recognise that it is important to understand the universal laws of physics – such as friction – and then use that understanding to help design safer roads and to drive more safely as individuals.

The laws of psychology are similarly universal. Psychological principles apply to health and wellbeing and to distress and problems. There simply isn’t an ‘abnormal psychology’ that applies to distress or explains ‘illnesses’ and a different ‘normal psychology’ that applies to everything else. There is just psychology.

Everybody makes sense of their world, and does so on the basis of the experiences that they have and the learning that occurs over their lifetime. We all use the same basic processes to understand the world, even if we come to very different conclusions.

The patterns and contingencies of reinforcement – rewards and punishments – shape us all: the basic psychology of behavioural learning is universal. We all learn to repeat those things that are reinforcing, and we all withdraw from things that cause us pain.

We all construct more or less useful frameworks for understanding the world, and we all use those frameworks to predict the future and guide our actions. We’re all using the same processes of learning and understanding, and those processes have similar effects on our behaviour and emotions.

However, because no one is exactly the same as anyone else, or has exactly the same experiences, we all make sense of the world in slightly different ways, with different consequences. But that’s entirely different from suggesting that there is some kind of ‘abnormal psychology’.

Instead, because applied psychologists use their understanding of psychology to solve real problems in the world, we could talk about clinical or educational or forensic psychology - if we must. Or about the psychology of psychological wellbeing, or even ‘mental health’ or offending, or parenting… just say what we mean without insulting people.

But not, in my opinion ‘abnormal psychology’. I’m afraid I just don’t think there is such a thing as ‘abnormal psychology’.

FAQs About Abnormal Psychology

What is the difference between abnormal psychology and clinical psychology?

Abnormal psychology focuses on the study of psychological disorders, while clinical psychology involves the assessment and treatment of these disorders.

Is abnormal psychology still taught in universities?

Yes, but many programs are shifting toward terms like "psychopathology" or "mental health psychology" to avoid stigma.

Can abnormal psychology be applied to everyday life?

Absolutely. Understanding psychological disorders can help reduce stigma, improve empathy, and promote mental health awareness.

The Future of Abnormal Psychology

As the field evolves, there is a growing shift toward more inclusive and compassionate frameworks, such as:

- Trauma-Informed Care: Recognizing the role of trauma in mental health.

- Positive Psychology: Focusing on strengths and well-being rather than pathology.

- Cultural Competence: Understanding how cultural context shapes mental health experiences.

The term "abnormal psychology" has played a crucial role in the history of mental health research, but its relevance is increasingly questioned. By embracing more inclusive and compassionate frameworks, we can better understand and support individuals experiencing mental distress. Whether you’re a student, professional, or simply curious about psychology, challenging the status quo is essential for progress.

Quality Resources

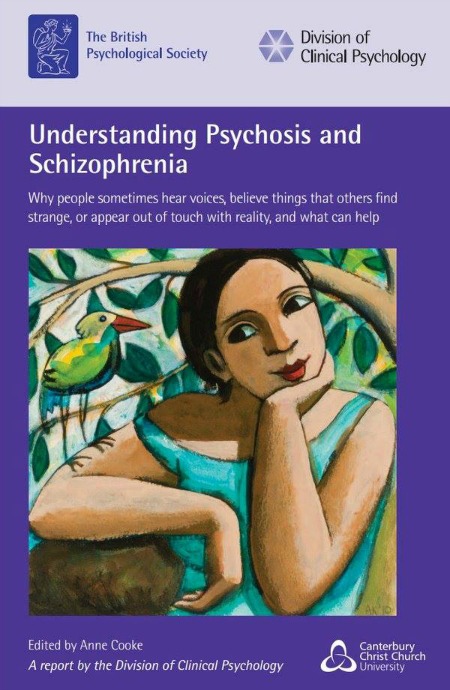

Edited by Anne Cooke, 'Understanding Psychosis and Schizophrenia' is an outstanding free resource that you can download for free along with another must read public information document 'Understanding Bipolar Disorder.' You can access both publications by clicking HERE.

Excellent presentation by Anne Cooke & Peter Kinderman at the Driving Us Crazy Film Festival 2015

Essential Reading

What does the word 'schizophrenia' mean to you? Perhaps your first thought is of someone with a medical condition that involves some kind of brain disease? But what if you knew that the person in question had been through a traumatic childhood? Would that change how you thought about their mental health? And what impact does this have on how we as a society interact with people with mental distress?

The first mainstream text to reconsider the traditional emphasis for what is commonly known as 'abnormal psychology'. Providing a comprehensive account of mental distress, this text challenges your preconceptions about what you think you know about mental health. Includes a foreword by award winning Richard Bentall and a chapter from service users.

See following link for full details.

Psychology, Mental Health and Distress

Recent Articles

-

Psychology Articles by David Webb

Jan 26, 26 04:52 AM

Discover psychology articles by David Webb, featuring science-based insights into why we think, feel, and behave the way we do. -

Why Doing Nothing Feels So Hard | Psychology of the Restless Mind

Jan 26, 26 04:42 AM

Why does doing nothing feel uncomfortable? Psychology research reveals how attention, the default mode network, and unstructured thought shape inner restlessness. -

Online Psychologist Australia: 7 Benefits of Choosing Online Therapy

Jan 22, 26 03:26 PM

Discover 7 key benefits of choosing an online psychologist in Australia, from better access and privacy to flexible scheduling and continuity of care.

Go Back To The Types of Psychology Page

Go From Abnormal Psychology Back To The Home Page

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.