Psychology Classics On Amazon

Happiness Hinges On Personality, So Initiatives To Improve Well-Being Need To Be Tailor-Made

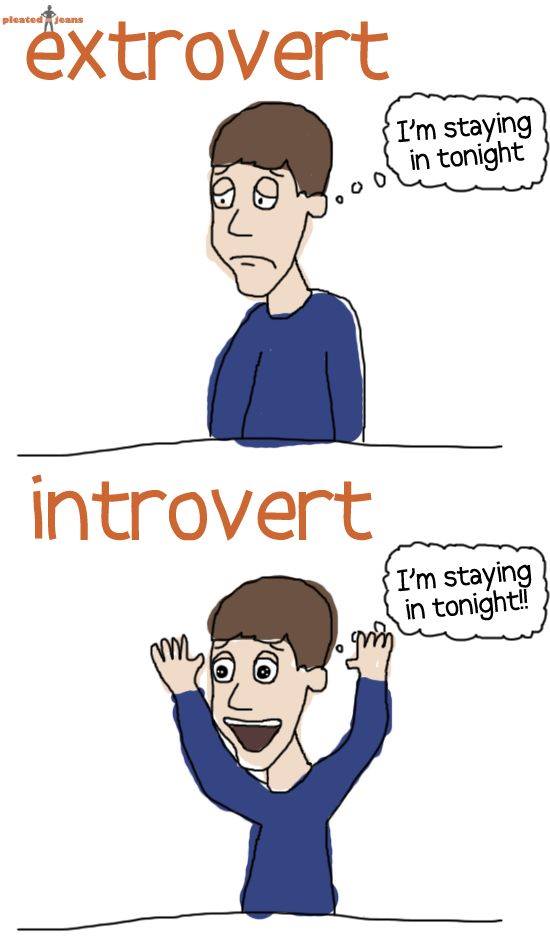

(Cartoon by Jeff Wysaski)

Happiness, it’s been said, is the goal of all human endeavour. Why else do we strive to improve medicine, strengthen economies, raise literacy, lower poverty, or fight prejudice? It all boils down to improving human well-being.

Psychologists have conducted hundreds of studies of the correlates of well-being. You might think well-being is determined by your circumstances — such as the size of your social circle or your pay cheque. These factors are important, but it turns out a far stronger role is played by your personality.

Extraversion linked to happiness

All aspects of our personality have links with different aspects of our well-being, but one personality trait that seems particularly important is extraversion. Extraversion describes the degree to which one behaves in a bold, assertive, gregarious, and outgoing way. Several studies have shown people who are more extraverted enjoy higher levels of well-being.

Some years ago, personality psychologists working in this area came across a powerful idea: what if we could harness the happiness of extraverts simply by acting more like they do? A wave of studies investigating this idea seemed to support it.

For example, lab experiments showed when people were instructed to act extraverted during an interactive task, they felt happier. Surprisingly, even introverts enjoyed acting extraverted in these studies.

Researchers have also used mobile devices to track people’s levels of extraverted behaviour and well-being in the real world. This, too, showed people feel happier when acting more extraverted. Again, even people who described themselves as highly introverted felt happiest when acting more like an extravert.

These findings appeared to suggest engaging in extraverted behaviour could be an effective tool for boosting well-being, and potentially form the basis of well-being programs and interventions.

But there were critical limitations to this research. Findings from the lab experiments — based on short, contrived interactions among strangers — might not necessarily apply in the real world. And the field studies that tracked people’s behaviour and well-being in the real world were correlational. This means they could not tell us whether acting extraverted during everyday life caused increases in well-being.

To resolve these uncertainties, we conducted the first randomised controlled trial of extraverted behaviour as a well-being intervention, recently published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General.

What did we find?

We randomly assigned participants in our study to act extraverted, or to a control condition comprising non-extraverted behaviours, for one week of their lives. An additional control group did not receive any acting instructions. We tracked multiple indicators of well-being throughout the week, and assessed well-being again at the end of the intervention.

On average, people in the “act extraverted” intervention reaped many well-being benefits — but these positive effects also hinged on personality. Specifically, more naturally extraverted people benefited the most, but those who were relatively introverted did not appear to benefit at all, and may have even suffered some well-being costs.

Although our findings are at odds with previous studies on acting extraverted, they support the cautions offered both by psychologists and self-help writers: there are costs to acting out of character.

Working with your personality

The fact our well-being critically depends on our personality sounds like bad news. We like to think we are masters of our destiny, and anyone can be whoever and however they want. But what if our destiny is constrained by our personality?

Our personality shapes our lives, but it also changes, and we can potentially affect these changes ourselves. Personal change may not be easy, but we now know personality is not “fixed”.

Also, the findings of our study don’t suggest you need to be extraverted to be happy. Rather, they show one specific well-being intervention is effective for extraverts but less so for introverts. What we now need is more research to help us better understand how well-being interventions can best take personality into account.

This is not a new idea. Similar insights underlie personalised medicine, and marketing researchers know advertising is more effective when tailored to the traits of the consumer. Similarly, researchers in positive psychology have often argued well-being interventions will be more effective if they’re matched to an individual’s personality.

There’s no silver bullet for happiness. If we want to build our well-being, we have to learn how to build it around our personalities.![]()

Luke Smillie, Senior Lecturer in Personality Psychology, University of Melbourne; Jessie Sun, PhD Student, University of California, Davis, and Rowan Jacques-Hamilton, Research Assistant, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

know someone who would be interested in reading this article? Share this page with them.

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.