Psychology Cartoons

The Article in Full

All professions are becoming appreciably more concerned with the importance of their "public image." Psychology, under the auspices of the APA, is no exception. The APA Policy and Planning Board (1948) suggested in its Annual Report that the association should try to create a better and more accurate public understanding of Psychology. Subsequently, in 1952, funds were appropriated for a professional public relations officer to be attached to the APA Central Office. More recently, Newman (1957) has stated that, in addition to causing the public to perceive psychology clearly and without distortion, "we must see ourselves accurately in the present situation and then we may go about our job in the future more usefully."

To assess one component of the public image of the psychologist - to see him through the eyes of others, and perhaps in true perspective - the present writers have theorized that a content or thematic analysis of cartoons might be relevant. It is believed that cartoon analysis has not been employed in this respect. Cartoons dramatize the issues and attitudes of the clay, and cartoon characters reflect the role expectations held by the public, for a person or group of people.

Newspapers, magazines, and journals provide the facts, the statistics, and the history of a society. However, Mills (1958) stated that, it is the cartoonists who hold to light the faults and failings and who point up the fads, foibles, and follies that amuse and worry society.

In order to determine how the psychologist appears, through the eyes of the cartoonist, the following general hypotheses were investigated:

1. Considerable overlap would occur between the public's role expectations of psychologist, psychiatrist, and various other undifferentiated but psychologically oriented personnel.

2. Psychology, both as a science and as a profession, generates little in the way of public interest regarding inter - or intraprofessional issues, or public issues, as indicated by the relative frequency of cartoon themes concerning psychologists.

3. While the APA increased its membership by over 250% from 1949 to 1959, public interest would not have kept pace as shown by the relative frequency of cartoon themes concerning psychologists.

4. Psychology has not kept pace in terms of the ratio of cartoon themes concerning psychology to total cartoon themes featuring the members of the family of professions and occupations requiring additional education beyond the AB.

DESIGN

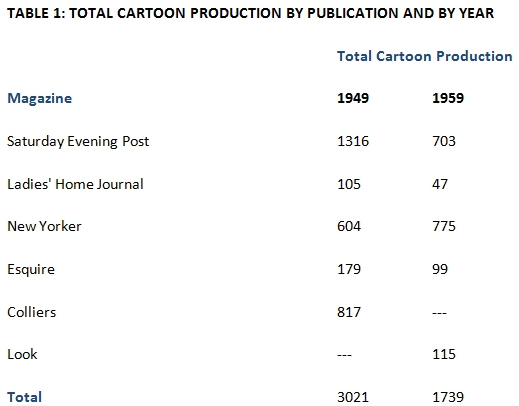

The total cartoon production obtained from the following magazines was counted, classified, and analyzed in terms of content and apparent cartoonist attitude: Saturday Evening Post, (1949 and 1959), Ladies' Home Journal (1949 and 1959), New Yorker (1949 and 1959), Esquire (1949 and 1959), Colliers (1949), and Look (1959).

The magazines were selected on the basis of their popularity (circulation), the quantity of their cartoon production, the range of interest indicated in terms of the "types" of magazines included, and the magazines' availability as determined by their inclusion in a large library's reading list. Four of the magazines met all of the criteria for selection. Two magazines, Colliers and Look, met all of the criteria except the criterion of "availability." Colliers was available until 1957 when it ceased publication. Look was not available in the library until 1954. The present writers decided to include these two magazines in view of the fact that they met the other criteria very well, and because the criteria were stringent enough to eliminate nearly all other popular magazines.

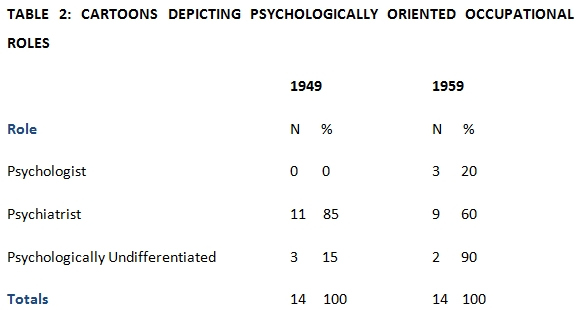

Upon analysis of the cartoons, all psychologically oriented professions were classified in terms of occupational role as: psychologist, psychiatrist, or undifferentiated but psychologically oriented personnel (including high school or vocational counselor, social worker, etc.).

Cartoons dealing with all professions were defined as those professions or occupations requiring additional education beyond (the 4-year baccalaureate. These professions and occupations include: physician, lawyer, judge, optometrist, scientist (undifferentiated), psychologist, dentist, psychiatrist, veterinarian, professor, and counselor.

Although military officers, teachers, clergymen, and orchestra conductors could have had advanced training, they were excluded from this category inasmuch as advanced education is not a prerequisite to their functioning in a professional status.

RESULTS

A total of 3,021 cartoons were reviewed for 1949 and 1,739 cartoons were obtained for review for 1959. It is apparent that a sharp reduction in cartoon production in most of the magazines employed has taken place over the 10-year time span as indicated by Table 1.

The 1949 cartoon production included three cartoons which could only be classified as undifferentiated professional. One could have represented either a psychologist or psychiatrist; another might have been a psychiatrist or MD; and the third one a counselor, lawyer, or consultant of some type. In 1959 two cartoons required a categorization of "undifferentiated professional" due to ambiguity. One depicted an individual who was either a psychiatrist or an MD; and the other portrayed an individual who could have been a MD, psychologist, or psychiatrist. These findings are summarized in Table 2.

It should be noted that out of more than three thousand cartoons analyzed in 1949 not one showed a clear-cut psychologist role. However, 10 years later, in 1959, 3 psychologist cartoons emerged out of a total of only 1,739 cartoons. It is heartening to note that while the APA did not quite triple its membership from 1949 to 1959, cartoon production pertaining to psychologists did increase a full 300% during that period - from zero to three!

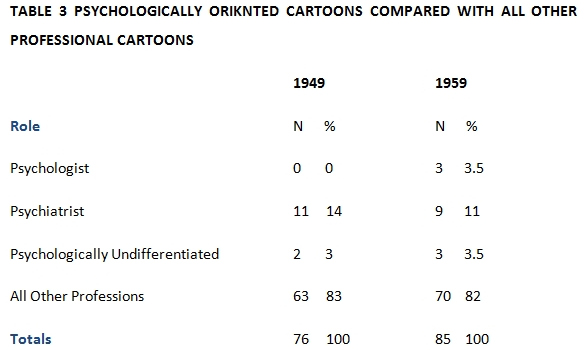

While total cartoon production decreased, a net increase in cartoons depicting all professional and scientific personnel occurred. A considerable amount of this increase can be accounted for by "mad scientists" constructing and operating electronic brains and computers. This increase, coupled with the net decrease in cartoons, created a situation whereby professional cartoons increased from 3% to 5% of the total cartoon production from 1949 to 1959.

The "all other professions" category of the total cartoon production portraying professional people held relatively constant percentagewise (83% in 1949 vs. 82% in 1959). The "psychologically undifferentiated" portion of the professional group increased from 3% to 3.5% of the total while psychology scored a net gain and thereby harvested 3.5% of the total professional cartoon category. These gains, as disclosed in Table 3, were presumably made at the expense of psychiatrists.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Assuming that the cartoon is an instrument of public opinion, an analysis of 4,760 cartoons contained in six popular magazines for the years 1949 and 1959 has led the present writers to the following conclusions:

1. Considerable overlap in public image does occur between psychologists, psychiatrists, and other psychologically oriented personnel although there does appear to be a trend toward more differentiation of roles. It is still probably true that "two-thirds of the public do not know who we are" as revealed by Cohen and Wiebe (1955) in their informal study.

2. Psychology as a science and as a profession does not appear to excite the public imagination and generate public interest. Of the three cartoons concerning psychologists, all were shown as professionals rather than scientists.

3. Contrary to the writers' hypothesis, psychology has kept pace with other members of the family of professions and occupations requiring more than 4 years of college preparation. This may be due to the aforementioned trend toward greater differentiation of occupational roles. The psychologist is seen as a practitioner either supplementing or supplanting the psychiatrist in his occupational role.

4. Symbols seem to be important, if not absolutely necessary, for the differentiation of occupational roles-at least through the eyes of the cartoonist. The physician is characterized by either his stethoscope or his reflector, the psychiatrist is pictured with his couch and/or his goatee, while the judge sits behind his bench, and the dentists and optometrists are busy with their instruments and implements. Meanwhile the psychologist does not seem to have any symbol to which he can lay easy claim as his own.

REFERENCES

AMERICAN PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION, Policy and Planning Board. Annual Report: 1948. Amer. Psychologist, 1948, 3, 187-192.

COHEN, J., & WIEBE, G. D. Who are these people? Amer. Psychologist, 1955, 10, 84-85.

MILLS, M. R. The Saturday Evening Post cartoon festival. New York: Button, 1958.

NEWMAN, E. B. Public relations-for what. Amer. Psychologist, 1957, 12, 509-514.

THE END

Back To Top Of The Page

Go Back To The Psychology Journal Articles Collection

Go From Psychology Cartoons Back To The Home Page

Enjoy this page? Please pay it forward. Here's how...

Would you prefer to share this page with others by linking to it?

- Click on the HTML link code below.

- Copy and paste it, adding a note of your own, into your blog, a Web page, forums, a blog comment, your Facebook account, or anywhere that someone would find this page valuable.