|

The Machinery of the MindMachinery of the Mind

Thinking About Becoming A Psychology Student? Find A Psychology School Near YouA few days ago a small fire occurred in a house near mine. I happened to be looking out of my window when a man rushed down the street to turn in an alarm at the corner box. In an almost unbelievably short time - not more than two or three minutes - a fire engine pulled up before the house. A few minutes later the blaze had been extinguished and the engine had departed. A Wonderful Alarm System This was no extraordinary occurrence; simply a commonplace incident of present day city life. Still, I could not but wonder at the swift passage of events that followed the ringing of the alarm. Here was a marvelous combination of human ingenuity and discipline. Automatically the touch of a finger on a switch within the alarm box had summoned a roaring engine to the exact location of the fire. Then, with perfect teamwork and precision, their trained firemen had gone about the work of putting out the blaze. And yet, as a psychologist, I had little reason to marvel at what I saw. For the complex electrical fire-alarm system and the perfect discipline of the firemen represented only an imperfect imitation of the wonderfully sensitive alarm system operating in every normal human body. At the heart of this system is a central control station - the brain. Leading from it to every "corner box" of the body is an elaborate network of wires - our nerves. And finally, responding to every interchange of messages or alarms, that flash along the nerves to and from the brain are our muscles, performing for us the movement necessary to protect and support our lives. On the degree of perfection with which this complicated nerve system functions, and on the precision and discipline of our muscles in responding to every signal flashed to the brain, depends largely our success in meeting tasks or emergencies that every-day life presents. To learn the secret of this wonderful network of living nerves and muscles, to discover its weaknesses, repair its faults, and to make it respond more surely to our common needs - this is the part of psychology. At one of the World Series baseball games in New York last fall I witnessed an incident that illustrated in a vivid way the workings of the human alarm system. One of the Yankee batsmen hit a fly ball over first base, well out in right field. It was beyond the reach of the first baseman and the right fielder - apparently a safe hit. And yet the fly was caught by Friach, second baseman of the Giants, ever though, when the ball was hit he was stationed farther away from its ultimate landing place than any other player. The reason Frisch caught the ball was this: Almost at the instant the batsman struck the ball, Frisch had started running in the direction it was traveling. In fact, to most people in the stands his first movement seemed to coincide with the crack of bat on ball. Messages Flashed To The Brain Yet the two events really were not simultaneous. Between the instant the bat touched the ball and the instant Frisch started to run, there was an infinitesimal pause. And during that pause, a highly complicated series of actions and reactions had taken place in his body - comparable to the transmission of electric signals and the resultant appearance of the fire engines, but infinitely more complex and infinitely more certain. The crack of the bat stirred into action delicate nerve centers controlling the man's vision and his hearing. From these nerve centers, sensitive nerves carried a report of that event to certain brain cells. These, accepting the message transmitted from the eyes and ears, retransmitted it along another line of nerves to the muscles that carried him in the direction of the ball. And not until these muscles received the relayed message did he move. That may seem like a long and complicated explanation of a process that took place in a space of time so short as to be virtually incalculable; but it is typical of the working of the wonderful human nervous system and its guiding power, the brain. Every time we perform a conscious action, there is just such an interchange of messages between our nerve centers, our brain and our muscles. If you accidentally touch the glowing end of a cigar you quickly draw your hand away. This may seem to you to be an instinctive action - one performed more or less automatically by your muscles without the direction of your brain. But is not. You pull your hand away because your brain, sending the message of pain from your finger tips, directs your muscles to remove it from the danger area, just as the brain of the baseball player directed his muscles to carry him toward the flying ball. Yet while processes of this sort may seem complicated, really they are elementary when compared with other and more amazing processes by which our brains and nerve systems serve our needs. Even the lower animals posses nervous organizations that guide them in avoiding danger or pain and enable them to perform action necessary to support life. The Chimpanzee Consider the chimpanzee. The chimpanzee has a high order of animal intelligence; it can do some things that are as yet beyond the capabilities of a child. But the animal can't reason and in a few months the child will outstrip it mentally. The chimpanzee lives by its animal instincts. It never can progress. But there is no limit to the progress of the child. Man Reasons The one important and essential difference that distinguishes man from the lower animals is that man possesses a mind. He reasons. His life is ruled not by every passing impulse that flashes across the transmisson lines of his nerves. Rather, his mind is master. His brain, the central station rules. It is the guiding power of his nervous system, and consequently of his body and its functions. Lock a cat in a box covered by a lid that will spring open at the touch of lever, and the cat will remain a prisoner. It will struggle madly, clawing at the sides of the box, hurling itself about as a protest against its confinement; but all its efforts will fail to bring release unless, of course, it should touch accidently the lever operating the lid. But lock a man in a similar box and observe how different are his actions. He will not not struggle, he will not hurry. He will consider his situation calmly until he discovers that by moving the lever he may cause the lid to rise and so gain his freedom. In every normal, healthy man the brain is ruler. It exercises its control over his muscles through certain groups of brain cells called motor centers, each controlling its own set of muscles. Long ago science by experiments with animals, discovered the specific locations of the motor centers controlling the movements of the legs, arms, face, fingers, in fact, every part of the body. Psychology, the scientific study of the mind, has revealed one extremely important fact about these motor centers that holds the key to success or failure. It is this: Impulses Needed Your brain though it is the ruler of your body, has not the power of itself to initiate thought; nor can it, of itself, direct your muscles to perform any definite action. It must receive, first, a suggestion of impulse from without. A ring of your doorbell, the entrance of another person into the room where you are reading, orsome other interruption, may cause you to put down your book or magazine - a thing which, if you are interested, you probably have no intention of doing. Or, take the case of Frisch, the Giants' second-baseman. His motor centers did not direct his muscles to move towards the fly ball until after his brain had perceived that movement was necessary if he was to intercept the ball. Why You Act Although you may be awake, you will not rise from your bed in the morning until the sunlight or the sight of your clock informs you that the time has come for you to be about your duties. On your way to take the street car to your office or shop you will not hurry unless you learn in some way that hurry is necessary because you have left your home at a later time than usual. Also, you probably would not be going to work at all had your brain not learned, either from your own experience in the past or by information you have received repeatedly from others, that you must work in order to live. That the mind cannot spin out thought of itself, that it will act only in response to some external impetus, undoubtedly is the most significant fact shown by psychology in its practical application to the every-day man, and an understanding of this fact furnishes the key that will unlock the storehouse of the hidden powers of the mind. We do nothing - we do not even perform the workaday actions necessary to keep the breath of life in our bodies, except in response to some external stimulus - the press of necessity, the orders of our employers, something of that sort. Nature has recognized this inertia of humankind and has supplied us at birth with the means of performing without the direction of the brain, the elementary actions necessary to living. Thus we breathe, swallow, and digest our food, send the blood coursing through our bodies, by what is known as reflex action - actions that are accomplished without interchange of messages between nerve centers, motor centers, and muscles. How The Brain Controls The Body

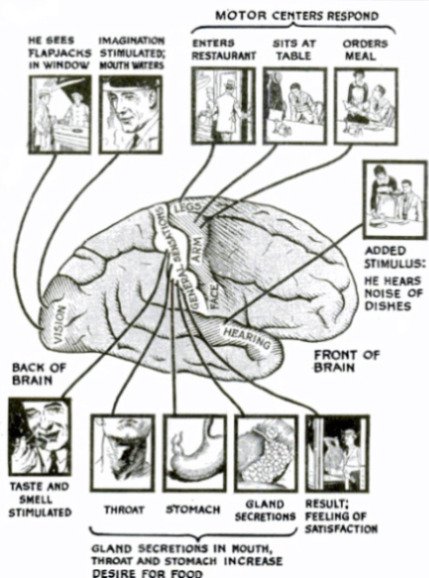

Here is a picture story of how the brain, receiving stimuli from without, transmits the sensation of hunger to the body and moves the muscles to responsive action. The man in the pictures first sees flapjacks cooking in the window. Through the visual center of the brain his imagination is stimulated. He imagines himself in the restaurant eating flapjacks, which causes stimulation of the senses of taste and smell and of certain glands of throat and stomach. Through their secretions, these glands bring increased desire for food - the mouth-watering sensation. Noises in the restaurant add still another stimulus. All these sense messages are transmitted through the motor centers to the muscles, which act to satisfy the hunger. Don't Wait For Necessary Prodding This is what governs most of the actions of the chimpanzee; why he can´t progress. But far too many of us go through life virtually letting our reflexes take care of us. We act only in response to the stimulus of necessity. We never seek a stimulus that will stir our minds into action, carrying us on to the heights of achievement where stand those whose success we envy and, excusing our own lethargy and laziness, attribute to luck. A few weeks ago I called at the office of a lawyer and found him in a most unhappy frame of mind. On his desk lay a great sheaf of unanswered correspondence. "I hate to write letters," he told me "These have been accumulating for a week, and I've been putting off replying to them from day to day until now that are enough of them to overwhelm me. What am I to do?" This lawyer is a really eminent man and his distress about what seemed to me to be a comparatively trivial matter quite amused me. Getting an Unpleasant Job Done "I don't know what you can do," I informed him, "except to buckle down and answer the letters. All of us have mental inhibitions; yours apparently take the form of a distaste for letter writing. This distaste places a brake on your brain when you approach that task. The task itself is not difficult, but you raise up difficulties - imaginary difficulties that become real - by brooding too much over your dislike for dictating letters. Undoubtedly you do really difficult and important work without trouble, because you concentrate on the work itself, raising up no imaginary difficulties, but rather using your faculties to remove the actual difficulties that the work contains. "Try this," I suggested. "Clasify your correspondence according to its importance. Begin by replying to the routine letters that require only routine answers. Then, by the time you reach the letters on which you must exert real thought, you probably will have acquired sufficient momentum to carry you through." He told me later that he had taken my advice. He found that the method I had suggested of "cranking up" his mind had banished the trouble his correspondence had given him previously. Why Amateurs Were Successful During the war, in the munition works at Watervliet, N. Y., I saw many young women of no previous training and of little mechanical skill performing the most intricate operations connected with the manufacture of firearms - work always before done by experts after years of experience. That these girls, called from homes, stores, offices, and factories to aid in supplying the sudden need for huge quantities of arms, were able to perform this intricate work satisfactorily was due entirely to the fact that they had not been informed that the tasks at which they were set were difficult. Had they been told that the work they were doing usually required years of practice, they would have become doubtful of their ability to perform it, and probably would have failed. As it was, they just took it as a routine task, and went ahead as did it. Psychological tests conducted by the army and navy showed indubitably that the average mental age of the officers selected from civil life during America's part in the World War was about 18 years. Certainly one would say that boys of 18 would not be fit to command troops in time of war. Yet under to leadership of these same officers the American forces carried out their share of the war with conspicuous success. Why? Because under the stress of war and the sudden responsibilities it brought them, these officers of 18 mental years quickly learned to use the mental powers that had been lying dormant while they had been carrying on the easy, even affairs of civil life. In other words, their brains received the necessary impetus from without. And they rose to the opportunities through the use of the brains, completing with success the most difficult job they ever had essayed. Napoleon's Pride His Impetus The French Revolution gave Napoleon his chance. Napoleon was a very small man. Indeed, people used to laugh at him because of his size, and, because he was sensitive, it hurt very much. Instead though, of bending humbly under the ridicule of his fellows, he was roused intensely by it. When opportunity came to him he gave the lie to the historians who were fond of saying that the world never again could produce another general as great as Caesar or Alexander. Nor is it necessary for a war or some other great emergency to arise to cause us to make use of the full powers of our minds. An American novelist who some critics call our greatest spent his boyhood in luxury. There was no necessity of his using his mind for any other purpose than devising ways to enjoy himself. At the death of his father, he inherited a large sum of money, and went to Europe, when he gave himself over to the expensive amusements which the Continent provides for the wealthy idler. In a couple of years he had wasted his fortune and faced the necessity of working or starving. In desperation he turned to his pen, and after a period of discouragement succeeded in catching the public fancy and winning both fame and wealth from his writings. In his case the necessity for supporting himself supplied the impetus which his mind required to stir it to action. Had the necessity not arisen, this man probably would have wasted his life. Poverty As A Brain Stimulus A famous financier of other days use to say that the best thing that could happen to a young man was that he should go in debt for some legitimate purpose. Similarly, a well-known jurist frequently expressed the opinion that the best environment in which a growing boy could be reared was one that place him under the necessity of supporting a widowed mother. Both of these men were speaking from their own experience. To one the discharge of a debt that he contracted to launch his first business enterprise was the spur that drove him to make full use of his mind. To the other it was the necessity of supporting his mother. A large percentage of the successful men of this age were the sons of struggling country pastors. This is not surprising. Early in life these men received the stern impetus of necessity, which taught them to use all the powers of their minds. The habits of mind they acquired as boys remained with them through life, leading them to greater and greater achievements. Adversity is A Great Teacher Most of us fear adversity. Yet adversity well may be considered a blessing in disguise, since to most of us it will prove the impetus we need to start our minds working to their full capacity. Francois Coppée, the distinguished French writer, in one of his books, tell the story of a banker who failed, and doing so ruined a half-dozen persons who had intrusted their money to him. Fleeing the country, he went to Canada, where in time he recouped his fortunes. Then it occurred to him that he should return to his native land to repair the harm he had done those who had suffered through his reverses. What was his surprise to find all of them far better off than they had been in the days before his failure. Adversity, the press of necessity, had supplied them with the mental impetus they needed to carry them on to succeed through their own efforts. This is a purely fictional story, but it is founded on a premise which psychology shows to be entirely true. Adversity, crises, sudden responsibility, almost invariably drive men to achieve merits beyond any they have dreamed. We see evidence of this about us constantly. The young man who starts a business enterprise on small capital will learn to work harder, to use his mind more than will a salaried employee, and his efforts will carry him on to success. Find Your Own Brain Stimuli A man suddenly advanced to a position of greater responsibility in the business world will rise to his new responsibilities, evidencing capacity for work and mental effort such as his fellows had not suspected he possessed. New business, the more responsible job, the sudden necessity for supporting a family supplies the impetus that the mind requires. Too many of us, lacking such responsibilities, crises, or the spur of necessity, potter through life, using our minds no more than we have to, satisfied as long as we are supplied with the bare necessities of existence. Through psychology we learn that the mind will not work except in response to an impetus from without; yet how many of us, if that impetus is not supplied by circumstances, try to supply it ourselves? That we can supply it, psychology also shows. We learn that while the mind, like the automobile, requires a crank to start it, yet once started, we can through our will guide it along whatever paths of thought we wish. Envy or Emulation? An order from your employer will start the engine of your mind working. Yet the direction in which your mind will travel after receiving that order rests entirely with you. You may grumble at the extra work you have been asked do. You may even, if you wish, flatly refuse to do it. Or you may - and you probably will, if you are wise - accept the order cheerfully and throttle your mental engine up to full speed to accomplish the task to the best of your ability. Likewise, the success of another will stimulate your mind into activity, but it rests with you whether that activity will take the form of envy and jealousy of him and complaint at your own lesser fortune, or the desire to emulate him and achieve success similar to his. It is a striking, but true, expression that the ordinary graduate of a high school in our time knows much more about a great many things than Aristotle, the wisest of men in his day, ever knew about them. But it was not Aristotle's knowledge that gained him his reputation as the greatest of thinkers - the sovereign of men who know - it was his power to use his information to the best advantage in thinking out the problems that lay around him. How the old Greek philosopher, who was deeply interested in psychology would have envied us our knowledge of the make-up of the nervous system and of its mode of action as far as that has gone! And yet we, to whom this knowledge is readily available, make scant use it, plodding along in the old-fashioned way, letting our instincts and the practice of whatever talents that are forced on us carry us through life. What is it that has put a brake on your brain? Whence springs the inhibitions that are holding you back? From laziness? From ill temper? From self satisfaction? From grumbling discontent? From lack of self-confidence? Look within yourself for the answer, and see that you give it truthfully. Once conscious of the thing that is impeding you, you have gone a long way toward banishing it. This you can do by calling on your will. Recognising your trouble and using your will to combat it, supplies the impetus your mind needs to start it working towards its full capacity. It All Rests With You And once started, its own momentum will carry it forward. Then difficult tasks will become simple and what had seemed impossible of accomplishment before will become relatively easy. It all rests with you. Once you make your mind to do a thing you will find you have the mental equipment with which to do it. You will find that you have hidden resources of power which you never suspected and these latent powers will carry you far on the road of success and happiness. But making up our minds emphatically enough to stir ourselves into acting is something that too few of us do. Instead, we let ourselves be guided by our sensations. We are ruled by our senses, while our will power lies dormant. Were we to awaken it, we should be able to accomplish ever so much more than we can ever be tempted to do by our senses. There lies the difference between the unsuccessful man and the successful one - in the use of the will. END OF ARTICLE Classic Articles All Psychology Students Should Read

This special Kindle collection consists of the most influential, infamous and iconic research articles ever published in the history of psychology. See following link for full details. The Psychology Classics Kindle Collection Go Back To The Main Self Help Page Go From The Machinery of the Mind Back To The Home Page

|