Psychology Classics On Amazon

The Association Method

Originally published in the Collected Papers on Analytical Psychology in 1916, The Association Method was the first of three lectures Carl Jung delivered at the celebration of the twentieth anniversary of the opening of Clark University in September, 1909.

The Article in Full

When you honored me with an invitation to lecture at Clark University, a wish was expressed that I should speak about my methods of work, and especially about the psychology of childhood. I hope to accomplish this task in the following manner: In my first lecture I will give to you the view points of my association methods; in my second I will discuss the significance of the familiar constellations; while in my third lecture I shall enter more fully into the psychology of the child.

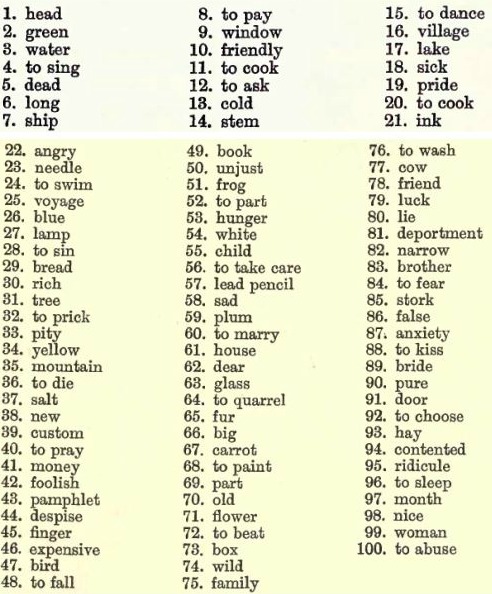

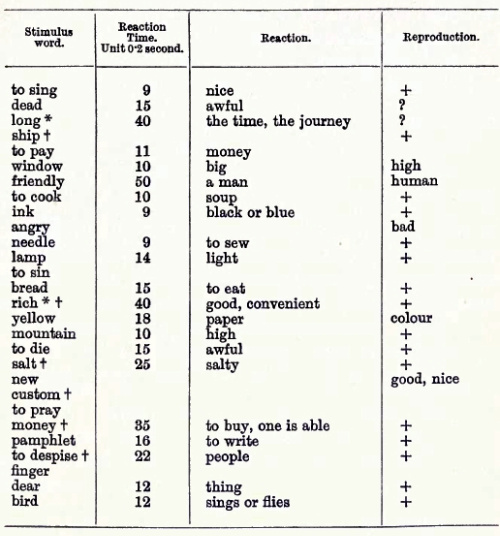

I might confine myself exclusively to my theoretical views, but I believe it will be better to illustrate my lectures with as many practical examples as possible. We will therefore occupy ourselves first with the association test which has been of great value to me both practically and theoretically. The history of the association method in vogue in psychology, as well as the method itself, is, of course, so familiar to you that there is no need to enlarge upon it. For practical purposes I make use of the following formula:

This formula has been constructed after many years of experience. The words are chosen and partially arranged in such a manner as to strike easily almost all complexes which occur in practice. As shown above, there is a regulated mixing of the grammatical qualities of the words. For this there are definite reasons - (The selection of these stimulus words was naturally made for the German language only, and would probably have to be considerably changed for the English language).

Before the experiment begins the test person receives the following instruction: "Answer as quickly as possible with the first word that occurs to your mind." This instruction is so simple that it can easily be followed. The work itself, moreover, appears extremely easy, so that it might be expected any one could accomplish it with the greatest facility and promptitude. But, contrary to expectation, the behavior is quite otherwise.

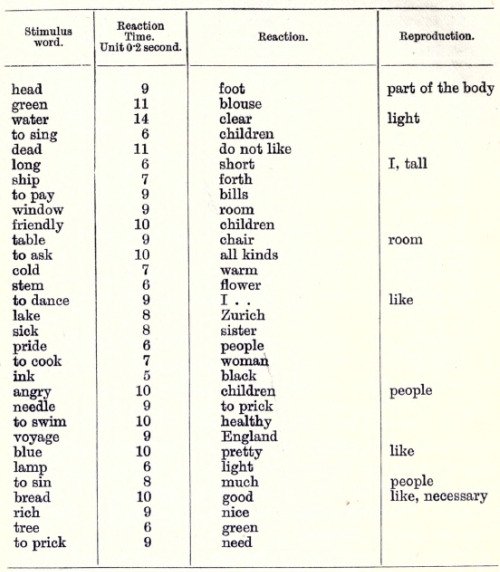

I. An Example of a Normal Reaction Time

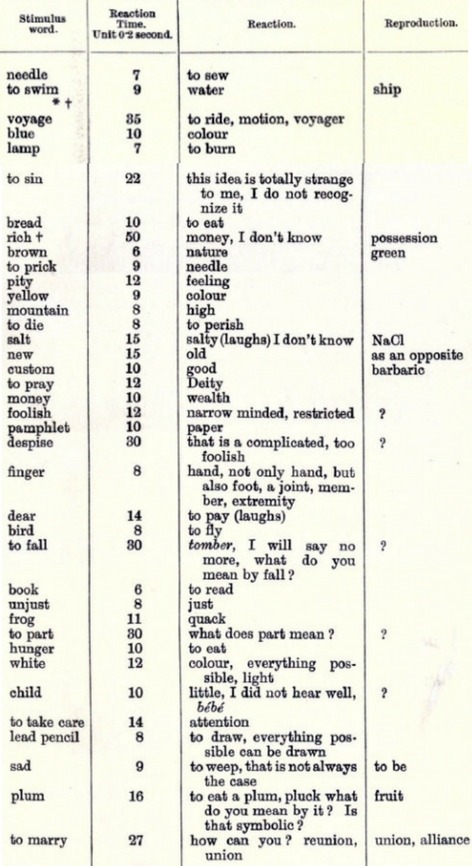

II. An Example of An Hysterical Reaction Time

(*) Denotes misunderstanding, (t) Denotes repetition of the stimulus words.

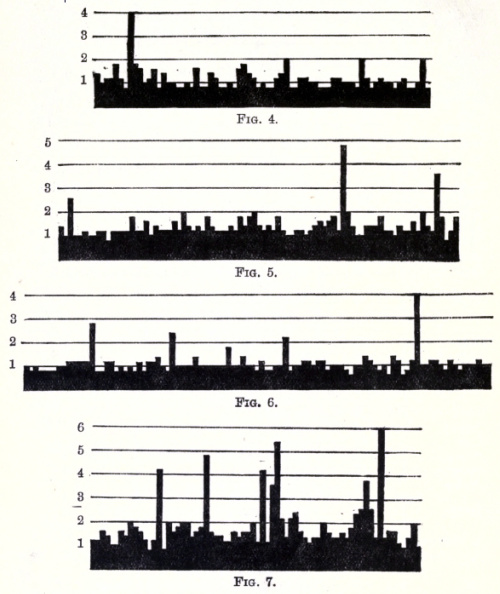

The following figures illustrate the reaction times in an association experiment in four normal test-persons. The height of each column denotes the length of the reaction time.

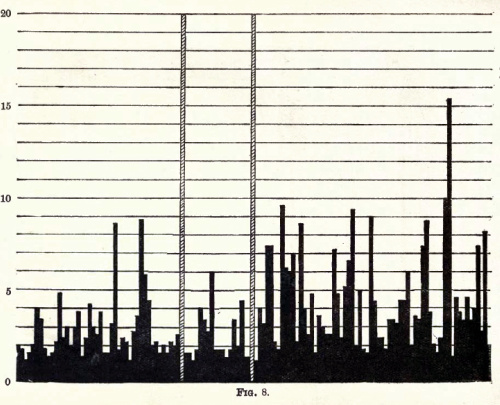

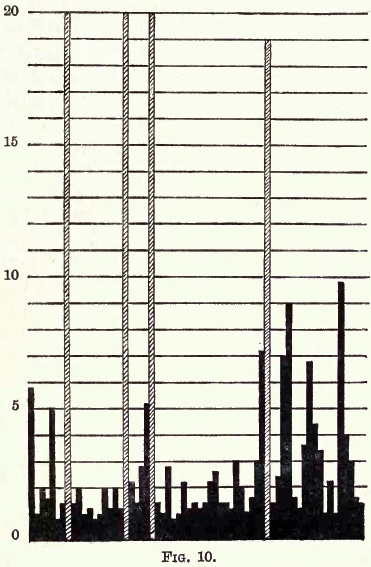

The following diagram shows the course of the reaction time in hysterical individuals. The light cross-hatched columns denote the places where the test-person was unable to react (so-called failures to react). The first thing that strikes us is the fact that many test persons show a marked prolongation of the reaction time. This would seem to be suggestive of intellectual difficulties, wrongly however, for we are often dealing with very intelligent persons of fluent speech.

The explanation lies rather in the emotions. In order to understand the matter comprehensively, we must bear in mind that the association experiments cannot deal with a separated psychic function, for any psychic occurrence is never a thing in itself, but is always the resultant of the entire psychological past.

The association experiment, too, is not merely a method for the reproduction of separated word couplets, but it is a kind of pastime, a conversation between experimenter and test-person. In a certain sense it is still more than that. Words really represent condensed actions, situations, and things. When I give a stimulus word to the test-person, which denotes an action, it is as if I represented to him the action itself, and asked him, "How do you behave towards it? What do you think of it? What would you do in this situation?" If I were a magician, I should cause the situation corresponding to the stimulus word to appear in reality, and placing the test-person in its midst, I should then study his manner of reaction.

The result of my stimulus words would thus undoubtedly approach infinitely nearer perfection. But as we are not magicians, we must be contented with the linguistic substitutes for reality; at the same time we must not forget that the stimulus word will almost without exception conjure up its corresponding situation. All depends on how the test-person reacts to this situation. The word "bride" or "bridegroom" will not evoke a simple reaction in a young lady; but the reaction will be deeply influenced by the strong feeling tones evoked, the more so if the experimenter be a man. It thus happens that the test-person is often unable to react quickly and smoothly to all stimulus words. There are certain stimulus words which denote actions, situations, or things, about which the test-person cannot think quickly and surely, and this fact is demonstrated in the association experiments. The examples which I have just given show an abundance of long reaction times and other disturbances. In this case the reaction to the stimulus word is in some way impeded, that is, the adaptation to the stimulus word is disturbed. The stimulus words therefore act upon us just as reality acts; indeed, a person who shows such great disturbances to the stimulus words, is in a certain sense but imperfectly adapted to reality. Disease itself is an imperfect adaptation; hence in this case we are dealing with something morbid in the psyche, with something which is either temporary or persistently pathological in character, that is, we are dealing with a psychoneurosis, with a functional disturbance of the mind. This rule, however, as we shall see later, is not without its exceptions.

Let us, in the first place, continue the discussion concerning the prolonged reaction time. It often happens that the test-person actually does not know what to answer to the stimulus word. He waives any reaction, and for the moment he totally fails to obey the original instructions, and shows himself incapable of adapting himself to the experimenter. If this phenomenon occurs frequently in an experiment, it signifies a high degree of disturbance in adjustment. I would call attention to the fact that it is quite indifferent what reason the test-person gives for the refusal. Some find that too many ideas suddenly occur to them; others, that they suffer from a deficiency of ideas. In most cases, however, the difficulties first perceived are so deterrent that they actually give up the whole reaction. The following example shows a case of hysteria with many failures of reaction:

(*) Denotes misunderstanding, (t) Denotes repetition of the stimulus words, (+) Reproduced unchanged.

In example II. we find a characteristic phenomenon. The test-person is not content with the requirements of the instruction, that is, she is not satisfied with one word, but reacts with many words. She apparently does more and better than the instruction requires, but in so doing she does not fulfil the requirements of the instruction. Thus she reacts: custom good barbaric; foolish narrow minded restricted; family big small everything possible.

These examples show in the first place that many other words connect themselves with the reaction word. The test person is unable to suppress the ideas which subsequently occur to her. She also pursues a certain tendency which perhaps is more exactly expressed in the following reaction: new old as an opposite. The addition of "as an opposite " denotes that the test-person has the desire to add something explanatory or supplementary. This tendency is also shown in the following reaction: finger not only hand, also foot a limb member extremity.

Here we have a whole series of supplements. It seems as if the reaction were not sufficient for the test-person, something else must always be added, as if what has already been said were incorrect or in some way imperfect. This feeling is what Janet designates the "sentiment d'incompletude," but this by no means explains everything. I go somewhat deeply into this phenomenon because it is very frequently met with in neurotic individuals. It is not merely a small and unimportant subsidiary manifestation demonstrable in an insignificant experiment, but rather an elemental and universal manifestation which plays a role in other ways in the psychic life of neurotics.

By his desire to supplement, the test-person betrays a tendency to give the experimenter more than he wants, he actually makes great efforts to find further mental occurrences in order finally to discover something quite satisfactory. If we translate this observation into the psychology of everyday life, it signifies that the test-person has a constant tendency to give to others more feeling than is required and expected. According to Freud, this is a sign of a reinforced objectlibido, that is, it is a compensation for an inner want of satisfaction and voidness of feeling. This elementary observation therefore displays one of the characteristics of hysterics, namely, the tendency to allow themselves to be carried away by everything, to attach themselves enthusiastically to everything, and always to promise too much and hence perform too little. Patients with this symptom are, in my experience, always hard to deal with; at first they are enthusiastically enamored of the physician, for a time going so far as to accept everything he says blindly; but they soon merge into an equally blind resistance against him, thus rendering any educative influence absolutely impossible.

We see therefore in this type of reaction an expression of a tendency to give more than is asked or expected. This tendency betrays itself also in other failures to follow the instruction:

to quarrel - angry - different things - I always quarrel at home;

to marry - how can you marry? - reunion - union; plum - to eat - to pluck - what do you mean by it? - is it symbolic?

to sin - this idea is quite strange to me, I do not recognise it.

These reactions show that the test-person gets away altogether from the situation of the experiment. For the instruction was, that he should answer only with the first word which occurs to him. But here we note that the stimulus words act with excessive strength, that they are taken as if they were direct personal questions. The test-person entirely forgets that we deal with mere words which stand in print before us, but finds a personal meaning in them; he tries to divine their intention and defend himself against them, thus altogether forgetting the original instructions.

This elementary observation discloses another common peculiarity of hysterics, namely, that of taking everything personally, of never being able to remain objective, and of allowing themselves to be carried away by momentary impressions; this again shows the characteristics of the enhanced object-libido.

Yet another sign of impeded adaptation is the often occurring repetitions of the stimulus words. The test-persons repeat the stimulus word as if they had not heard or understood it distinctly. They repeat it just as we repeat a difficult question in order to grasp it better before answering. This same tendency is shown in the experiment. The questions are repeated because the stimulus words act on hysterical individuals in much the same way as difficult personal questions. In principle it is the same phenomenon as the subsequent completion of the reaction.

In many experiments we observe that the same reaction constantly reappears to the most varied stimulus words. These words seem to possess a special reproduction tendency, and it is very interesting to examine their relationship to the test-person. For example, I have observed a case in which the patient repeated the word "short" a great many times and often in places where it had no meaning. The test person could not directly state the reason for the repetition of the word "short." From experience I knew that such predicates always relate either to the test-person himself or to the person nearest to him. I assumed that in this word "short" he designated himself, and that in this way he helped to express something very painful to him. The test person is of very small stature. He is the youngest of four brothers, who, in contrast to himself, are all tall. He was always the "child" in the family; he was nicknamed "Short" and was treated by all as the "little one." This resulted in a total loss of self-confidence. Although he was intelligent, and despite long study, he could not decide to present himself for examination; he finally became impotent, and merged into a psychosis in which, whenever he was alone, he took delight in walking about in his room on his toes in order to appear taller. The word " short," therefore, stood to him for a great many painful experiences. This is usually the case with the perseverated words ; they always contain something of importance for the individual psychology of the test-person.

The signs thus far discussed are not found spread about in an arbitrary way through the whole experiment, but are seen in very definite places, namely, where the stimulus words strike against emotionally accentuated complexes. This observation is the foundation of the so-called "diagnosis of facts" (Tatbestandsdiagnostik). This method is employed to discover, by means of an association experiment, which is the culprit among a number of persons suspected of a crime. That this is possible I will demonstrate by the brief recital of a concrete case. On the 6th of February, 1908, our supervisor reported to me that a nurse complained to her of having been robbed during the forenoon of the previous day. The facts were as follows: The nurse kept her money, amounting to 70 francs, in a pocket-book which she had placed in her cupboard where she also kept her clothes. The cupboard contained two compartments, of which one belonged to the nurse who was robbed, and the other to the head nurse. These two nurses and a third one, who was an intimate friend of the head nurse, slept in the room where the cupboard was. This room was in a section which was occupied in common by six nurses who had at all times free access to this room. Given such a state of affairs it is not to be wondered that the supervisor shrugged her shoulders when I asked her whom she most suspected.

Further investigation showed that on the morning of the theft, the above-mentioned friend of the head nurse was slightly indisposed and remained the whole morning in bed in the room. Hence, following the indications of the plaintiff, the theft could have taken place only in the afternoon. Of the other four nurses upon whom suspicion could possibly fall, there was one who attended regularly to the cleaning of the room in question, while the remaining three had nothing to do in it, nor was it shown that any of them had spent any time there on the previous day.

It was therefore natural that the last three nurses should be regarded for the time being as less implicated, and I therefore began by subjecting the first three to the experiment.

From the information I had obtained of the case, I knew that the cupboard was locked but that the key was kept near by in a very conspicuous place, that on opening the cupboard the first thing which would strike the eye was a fur boa, and, moreover, that the pocket-book was between the linen in an inconspicuous place. The pocket-book was of dark reddish leather, and contained the following objects: a 50-franc banknote, a 20-franc piece, some centimes, a small silver watchchain, a stencil used in the lunatic asylum to mark the kitchen utensils, and a small receipt from Dosenbach's shoeshop in Zurich.

Besides the plaintiff and the guilty one, only the head nurse knew the exact particulars of the deed, for as soon as the former missed her money she immediately asked the head nurse to help her find it, thus the head nurse had been able to learn the smallest details, which naturally rendered the experiment still more difficult, for she was precisely the one most suspected. The conditions for the experiment were better for the others, since they knew nothing concerning the particulars of the deed, and some not even that a theft had been committed. As critical stimulus words I selected the name of the robbed nurse, plus the following words: cupboard, door, open, key, yesterday, banknote, gold, 70, 50, 20, money, watch, pocket-book, chain, silver, to hide, fur, dark reddish, leather, centimes, stencil, receipt, Dosenbach. Besides these words which referred directly to the deed, I took also the following, which had a special effective value : theft, to take, to steal, suspicion, blame, court, police, to lie, to fear, to discover, to arrest, innocent.

The objection is often made to the last species of words that they may produce a strong affective resentment even in innocent persons, and for that reason one cannot attribute to them any comparative value. Nevertheless, it may always be questioned whether the affective resentment of an innocent person will have the same effect on the association as that of a guilty one, and that question can only be authoritatively answered by experience. Until the contrary is demonstrated, I maintain that words of the above-mentioned type may profitably be used.

I distributed these critical words among twice as many indifferent stimulus words in such a manner that each critical word was followed by two indifferent ones. As a rule it is well to follow up the critical words by indifferent words in order that the action of the first may be clearly distinguished. But one may also follow up one critical word by another, especially if one wishes to bring into relief the action of the second. Thus I placed together "darkish red" and "leather," and "chain" and "silver."

After this preparatory work I undertook the experiment with the three above-mentioned nurses. As examinations of this kind can be rendered into a foreign tongue only with the greatest difficulty, I will content myself with presenting the general results, and with giving some examples. I first undertook the experiment with the friend of the head nurse, and judging by the circumstances she appeared only slightly moved. The head nurse was next examined; she showed marked excitement, her pulse being 120 per minute immediately after the experiment. The last to be examined was the nurse who attended to the cleaning of the room in which the theft occurred. She was the most tranquil of the three; she displayed but little embarrassment, and only in the course of the experiment did it occur to her that she was suspected of stealing, a fact which manifestly disturbed her towards the end of the experiment.

The general impression from the examination spoke strongly against the head nurse. It seemed to me that she evinced a very "suspicious," or I might almost say, "impudent" countenance. With the definite idea of finding in her the guilty one I set about adding up the results.

One can make use of many special methods of computing, but they are not all equally good and equally exact. (One must always resort to calculation, as appearances are enormously deceptive.) The method which is most to be recommended is that of the probable average of the reaction time. It shows at a glance the difficulties which the person in the experiment had to overcome in the reaction.

The technique of this calculation is very simple. The probable average is the middle number of the various reaction times arranged in a series. The reaction times are, for example, (Reaction times are always given in fifths of a second) placed in the following manner: 5,5,5,7,7,7,7, 8,9,9,9, 12, 13, 14. The number found in the middle (8) is the probable average of this series. Following the order of the experiment, I shall denote the friend of the head nurse by the letter A, the head nurse by B, and the third nurse by C.

The probable averages of the reaction are:

A 10.0

B 12.0

C 13.5

No conclusions can be drawn from this result. But the average reaction times calculated separately for the indifferent reactions, for the critical, and for those immediately following the critical (post-critical) are more interesting.

From this example we see that whereas A has the shortest reaction time for the indifferent reactions, she shows in comparison to the other two persons of the experiment, the longest time for the critical reactions.

The Probable Average of The Reaction Time

For A B C

Indifferent reactions 10.0, 11.0, 12.0

Critical reactions 16.0, 13.0, 15.0

Post-critical reactions 10.0, 11.0, 13.0

The difference between the reaction times, let us say between the indifferent and the critical, is 6 for A, 2 for B, and 3 for C, that is, it is more than double for A when compared with the other two persons.

In the same way we can calculate how many complex indicators there are on an average for the indifferent, critical, etc., reactions.

The Average Complex-Indicators For Each Reaction

For A B C

Indifferent reactions 0.6, 0.9, 0.8

Critical reactions 1.3, 0.9, 1.2

Post-critical reactions 0.6, 1.0, 0.8

The difference between the indifferent and critical reactions for A = 0.7, for B = 0, for C = 0.4. A is again the highest.

Another question to consider is, in what special way do the imperfect reactions behave?

The result for A = 34%, for B = 28%, and for C = 30%. Here, too, A reaches the highest value, and in this, I believe, we see the characteristic moment of the guilt-complex in A. I am, however, unable to explain here circumstantially the reasons why I maintain that memory errors are related to an emotional complex, as this would lead me beyond the limits of the present work. I therefore refer the reader to my work "Ueber die Reproductionsstorrungen im Associationsexperiment" (IX Beitrag der Diagnost. Associat. Studien).

As it often happens that an association of strong feeling tone produces in the experiment a perseveration, with the result that not only the critical association, but also two or three successive associations are imperfectly reproduced, it will be very interesting to see how many imperfect reproductions are so arranged in the series in our cases. The result of computation shows that the imperfect reproductions thus arranged in series are tor A 64.7%, for B 55.5%, and for C 30.0%.

Again we find that A has the greatest percentage. To be sure, this may partially depend on the fact that A also possesses the greatest number of imperfect reproductions. Given a small quantity of reactions, it is usual that the greater the total number of the same, the more imperfect reactions will occur in groups. But in order that this should be probable it could not occur in so great a measure as in cur case, where, on the other hand, B and C have not a much smaller number of imperfect reactions when compared to A. It is significant that C with her slight emotions during the experiment shows the minimum of imperfect reproductions arranged in series.

As imperfect reproductions are also complex indicators, it is necessary to see how they distribute themselves in respect to the indifferent, critical, etc., reactions.

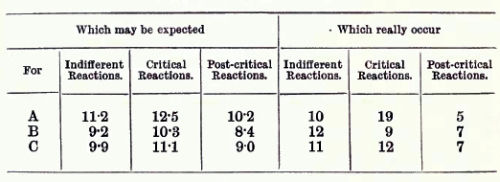

It is hardly necessary to bring into prominence the differences between the indifferent and the critical reactions of the various subjects as shown by the resulting numbers of the table. In this respect, too, A occupies first place.

Imperfect Reproductions Which Occur

In A B C

Indifferent reactions 10, 12, 11

Critical reactions 19, 9, 12

Post-critical reactions 5, 7, 7

Naturally, here, too, there is a probability that the greater the quantity of the imperfect reproductions the greater is their number in the critical reactions. If we suppose that the imperfect reproductions are distributed regularly and without choice, among all the reactions, there will be a greater number of them for A (in comparison with B and C) even as reactions to critical words, since A has the greater number of imperfect reproductions. Admitting such a uniform distribution of the imperfect reproductions, it is easy to calculate how many we ought to expect to belong to each individual kind of reaction.

From this calculation it appears that the disturbances of reproductions which concern the critical reactions for A greatly surpass the number expected, for C they are 0.9 higher, while for B they are lower.

Imperfect Reproductions

All this points to the fact that in the subject A the critical stimulus words acted with the greatest intensity, and hence the greatest suspicion falls on A. Practically one may assume the probability of this person's guilt. The same evening A made a complete confession of the theft, and thus the success of the experiment was confirmed.

Such a result is undoubtedly of scientific interest and worthy of serious consideration. There is much in experimental psychology which is of less use than the material exemplified in this test. Putting the theoretical interest altogether aside, we have here something that is not to be despised from a practical point of view, to wit, a culprit has been brought to light in a much easier and shorter way than is customary. What has been possible once or twice ought to be possible again, and it is well worth while to investigate some means of rendering the method increasingly capable of rapid and sure results.

This application of the experiment shows that it is possible to strike a concealed, indeed an unconscious complex by means of a stimulus word; and conversely we may assume with great certainty that behind a reaction which shows a complex indicator there is a hidden complex, even though the test-person strongly denies it. One must get rid of the idea that educated and intelligent test-persons are able to see and admit their own complexes. Every human mind contains much that is unacknowledged and hence unconscious as such; and no one can boast that he stands completely above his complexes. Those who persist in maintaining that they can, are not aware of the spectacles upon their noses.

It has long been thought that the association experiment enables one to distinguish certain intellectual types. That is not the case. The experiment does not give us any particular insight into the purely intellectual, but rather into the emotional processes. To be sure we can erect certain types of reaction; they are not, however, based on intellectual peculiarities, but depend entirely on the proportionate emotional states. Educated test-persons usually show superficial and linguistically deep-rooted associations, whereas the uneducated form more valuable associations and often of ingenious significance.

This behavior would be paradoxical from an intellectual viewpoint. The meaningful associations of the uneducated are not really the product of intellectual thinking, but are simply the results of a special emotional state. The whole thing is more important to the uneducated, his emotion is greater, and for that reason he pays more attention to the experiment than the educated person, and his associations are therefore more significant. Apart from those determined by education, we have to consider three principal individual types:

1. An objective type with undisturbed reactions.

2. A so-called complex type with many disturbances in the experiment occasioned by the constellation of a complex.

3. A so-called definition-type. This type consists in the fact that the reaction always gives an explanation or a definition of the content of the stimulus word; e.g. apple, - a tree-fruit;table, - a piece of household furniture; to promenade, - an activity; father, - chief of the family.

This type is chiefly found in stupid persons, and it is therefore quite usual in imbecility. But it can also be found in persons who are not really stupid, but who do not wish to be taken as stupid. Thus a young student from whom associations were taken by an older intelligent woman student reacted altogether with definitions. The test-person was of the opinion that it was an examination in intelligence, and therefore directed most of his attention to the significance of the stimulus words; his associations, therefore, looked like those of an idiot. All idiots, however, do not react with definitions; probably only those react in this way who would like to appear smarter than they are, that is, those to whom their stupidity is painful. I call this widespread complex the "intelligence-complex." A normal test-person reacts in a most overdrawn manner as follows:

anxiety - heart anguish; to kiss - love's unfolding; to kiss - perception of friendship.

This type gives a constrained and unnatural impression. The test-persons wish to be more than they are, they wish to exert more influence than they really have. Hence we see that persons with an intelligence complex are usually unnatural and constrained; that they are always somewhat stilted, or flowery; they show a predilection for complicated foreign words, high-sounding quotations, and other intellectual ornaments. In this way they wish to influence their fellow beings, they wish to impress others with their apparent education and intelligence, and thus to compensate for their painful feeling of stupidity. The definition type is closely related to the predicate type, or, to express it more precisely, to the predicate type expressing personal judgment (Wertprddikattypus). For example:

flower - pretty;money - convenient; animal - ugly; knife - dangerous; death - ghastly.

In the definition type the intellectual significance of the stimulus word is rendered prominent, but in the predicate type its emotional significance. There are predicate types which show great exaggeration where reactions such as the following appear:

piano - horrible; to sing - heavenly; mother - ardently loved; father - something good, nice, holy.

In the definition type an absolutely intellectual make-up is manifested or rather simulated, but here there is a very emotional one. Yet, just as the definition type really conceals a lack of intelligence, so the excessive emotional expression conceals or overcompensates an emotional deficiency. This conclusion is very interestingly illustrated by the following discovery: On investigating the influence of the familiar milieus on the association type it was found that young people seldom possess a predicate type, but that, on the other hand, the predicate type increases in frequency with advancing age. In women the increase of the predicate type begins a little after the 40th year, and in men after the 60th. That is the precise time when, owing to the deficiency of sexuality, there actually occurs considerable emotional loss. If a test-person evinces a distinct predicate type, it may always be inferred that a marked internal emotional deficiency is thereby compensated. Still, one cannot reason conversely, namely, that an inner emotional deficiency must produce a predicate type, no more than that idiocy directly produces a definition type. A predicate type can also betray itself through the external behavior, as, for example, through a particular affectation, enthusiastic exclamations, an embellished behavior, and the constrained sounding language so often observed in society.

The complex type shows no particular tendency except the concealment of a complex, whereas the definition and predicate types betray a positive tendency to 'exert in some way a definite influence on the experimenter. But whereas the definition type tends to bring to light its intelligence, the predicate type displays its emotion. I need hardly add of what importance such determinations are for the diagnosis of character.

After finishing an association experiment I usually add another of a different kind, the so-called reproduction experiment. I repeat the same stimulus words and ask the test persons whether they still remember their former reactions. In many instances the memory fails, and as experience shows, these locations are stimulus words which touched an emotionally accentuated complex, or stimulus words immediately following such critical words.

This phenomenon has been designated as paradoxical and contrary to all experience. For it is known that emotionally accentuated things are better retained in memory than indifferent things. This is quite true, but it does not hold for the linguistic expression of an emotionally accentuated content. On the contrary, one very easily forgets what he has said under emotion, one is even apt to contradict himself about it. Indeed, the efficacy of cross-examinations in court depends on this fact. The reproduction method therefore serves to render still more prominent the complex stimulus. In normal persons we usually find a limited number of false reproductions, seldom more than 19-20 per cent., while in abnormal persons, especially in hysterics, we often find from 20-40 per cent, of false reproductions. The reproduction certainty is therefore in certain cases a measure for the emotivity of the test-person.

By far the larger number of neurotics show a pronounced tendency to cover up their intimate affairs in impenetrable darkness, even from the doctor, so that he finds it very difficult to form a proper picture of the patient's psychology. In such cases I am greatly assisted by the association experiment. When the experiment is finished, I first look over the general course of the reaction times. I see a great many very prolonged intervals; this means that the patient can only adjust himself with difficulty, that his psychological functions proceed with marked internal friction, with resistances. The greater number of neurotics react only under great and very definite resistances; there are, however, others in whom the average reaction times are as short as in the normal, and in whom the other complex indicators are lacking, but, despite that fact, they undoubtedly present neurotic symptoms. These rare cases are especially found among very intelligent and educated persons, chronic patients who, after many years of practice, have learned to control their outward behavior and therefore outwardly display very little if any trace of their neuroses. The superficial observer would take them for normal, yet in some places they show disturbances which betray the repressed complex.

After examining the reaction times I turn my attention to the type of the association to ascertain with what type I am dealing. If it is a predicate type I draw the conclusions which I have detailed above; if it is a complex type I try to ascertain the nature of the complex. With the necessary experience one can readily emancipate one's judgment from the test-person's statements and almost without any previous knowledge of the test-persons it is possible under certain circumstances to read the most intimate complexes from the results of the experiment. I look at first for the reproduction words and put them together, and then I look for the stimulus words which show the greatest disturbances. In many cases merely assorting these words suffices to unearth the complex. In some cases it is necessary to put a question here and there. The matter is well illustrated by the following concrete example:

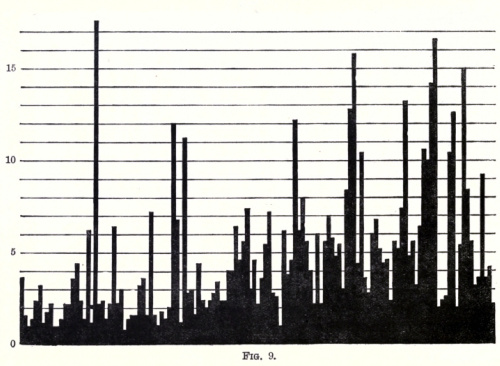

It concerns an educated woman of 30 years of age, married three years previously. Since her marriage she has suffered from episodic excitement in which she is violently jealous of her husband. The marriage is a happy one in every other respect, and it should be noted that the husband gives no cause for the jealousy. The patient is sure that she loves him and that her excited states are groundless. She cannot imagine whence these excited states originate, and feels quite perplexed over them. It is to be noted that she is a catholic and has been brought up religiously, while her husband is a protestant. This difference of religion did not admittedly play any part. A more thorough anamnesis showed the existence of an extreme prudishness. Thus, for example, no one was allowed to talk in the patient's presence about her sister's childbirth, because the sexual moment suggested therein caused her the greatest excitement. She always undressed in the adjoining room and never in her husband's presence, etc. At the age of 27 she was supposed to have had no idea how children were born. The associations gave the results shown in the accompanying chart.

The stimulus words characterized by marked disturbances are the following: yellow, to pray, to separate, to marry, to quarrel, old, family, happiness, false, fear, to kiss, bride, to choose, contented. The strongest disturbances are found in the following stimulus words: to pray, to marry, happiness, false, fear, and contented. These words, therefore, more than any others, seem to strike the complex. The conclusions that can be drawn from this is that she is not indifferent to the fact that her husband is a protestant, that she again thinks of praying, believes there is something wrong with marriage, that she is false, entertains fancies of faithlessness, is afraid (of the husband? of the future?), she is not contented with her choice (to choose) and she thinks of separation. The patient therefore has a separation complex, for she is very discontented with her married life. When I told her this result she was affected and at first attempted to deny it, then to mince over it, but finally she admitted everything I said and added more. She reproduced a large number of fancies of faithlessness, reproaches against her husband, etc. Her prudishness and jealousy were merely a projection of her own sexual wishes on her husband. Because she was faithless in her fancies and did not admit it to herself she was jealous of her husband.

It is impossible in a lecture to give a review of all the manifold uses of the association experiment. I must content myself with having demonstrated to you a few of its chief uses.

Learn all about the life and work of Carl Jung

Available from Amazon (prime eligible) in a range of colors for women and men, this stylishly sinister Shadow Self T-Shirt is perfect for anybody with an interest in Jungian archetypes, analytic psychology and the "darker side" of the human psyche. Also great for psych majors, psychotherapists and depth psychologists who like to add a psychological twist to their Halloween celebrations.

Recent Articles

-

Cute Aggression Explained: Why We Want to Squeeze Adorable Things

Apr 09, 25 01:24 PM

Overwhelmed by cuteness? Discover the science behind cute aggression, the brain's quirky way of handling too much joy. You’ll never see cute the same again. -

Psychology Book Marketing Services

Apr 08, 25 11:44 AM

Want a massive audience of psychology lovers to know about your book? I can help! -

Unparalleled Psychology Advertising Opportunities

Apr 08, 25 11:43 AM

Psychology Advertising: Connect With Hundreds Of Thousands Psychology Enthusiasts

Please help support this website by visiting the All About Psychology Amazon Store to check out an awesome collection of psychology books, gifts and T-shirts.

Go To The Classic Psychology Journal Articles Page

Go From The Association Method To The Home Page